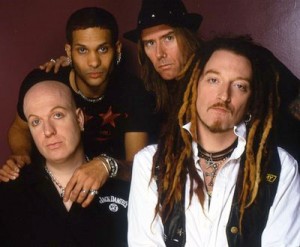

FOREWORD: Hard-partying Tucson-originated Seattle-exposed rockers, the Supersuckers, sure like to live the ‘high life.’ In ’99, I had the great fortune to have a late afternoon chat with the fellas over many free beers. And I hung out with them previously during some industry party where my High Times friends took hold. But by ‘03s Motherfuckers Be Trippin’ the party was almost over for them. Who knows if front man Eddie Spaghetti and twin guitarists Dan Bolton and Ron Heathman will re-form their fantastic boho combo. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

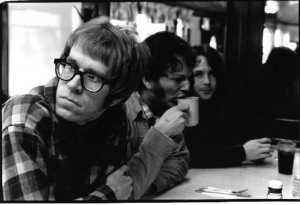

Wearing an ever-present beige cowboy hat and rock star shades, Supersuckers vocalist/ bassist Eddie Spaghetti detailed The Evil Powers Of Rock ‘N’ Roll (Aces & Eights/ Koch) for a sardine-packed September 1st Tramps show. Bold enough to pull out the opening bars of AC/DC’s “For Those About To Rock, We Salute You” as an eye-opening introduction, this fiery, unrestricted Seattle-by-way-of-Tucson quartet pumped out a steady stream of revved up punk, honky tonk, and Texas boogie.

Feeling compelled to sing about liquor and narcotics, Spaghetti’s “couldn’t care less” boho attitude infiltrated riotous fare like the fist-shakin’ “I Want The Drugs” and “Drink & Complain.” Between the raucous Southern-bound twin guitar riffage by Ron Heathman and Dan “Thunder” Bolton and the driving propulsion of drummer Dancing Eagle, the Supersuckers live show offers brash swagger and unbridled urgency. With a tip of the hat to ‘70s rock, they rip up Thin Lizzy’s “Cowboy Song” (dedicated to the memory of Phil Lynott) and unleash a dead-on instrumental encore of James Gang’s “Funk #49.”

Knowing no musical boundaries, the Supersuckers teamed up with living Country legend Steve Earle for a ‘97 EP and topped that with the high lonesome Western folk of Must’ve Been High. And as great as the 90 minute Tramps set was, nothing could beat the time they pulled off double duty delivering a Country-rooted set before returning for a full hour of heavy rock at Coney Island High.

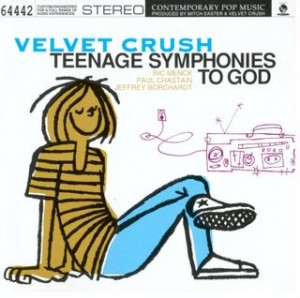

After recording with respected producers Jack Endino (‘92s dazzling The Smoke Of Hell), Conrad Uno (‘94s restless La Mano Cornuda), and Paul Leary of the Butthole Surfers (‘95s Sacrilicious Sounds of the Supersuckers with ex-Didjits guitarist Rick Sims temporarily replacing Heathman), they decided to leave the knob twisting of Evil Powers to Fastbacks frontman Kurt Bloch. Concurrently, an ace compilation, The Greatest Rock And Roll Band in the World, trudges through LP highlights, EP tracks, B-sides, soundtrack trash, a hard-to-find version of Ice Cube’s “Dead Homiez,” and acoustic side project the Junkyard Dogs’ “Wake Me When It’s Over.”

I spoke with the band at Manhattan’s Gramercy Park Hotel two days prior to the Tramps show.

Tell me about The Evil Powers of Rock ‘N’ Roll.

Tell me about The Evil Powers of Rock ‘N’ Roll.

RON HEATHMAN: It’s a return to rock and roll. We recorded a country record and then a rock record which got held up by our label. So we re-recorded Evil Powers and began doing what we should be doing. There’s not an acoustic guitar to be found. The songwriting process is the same and it’s the best LP we’ve ever made.

How did Kurt Bloch’s production affect Evil Powers?

RON: It was a blast working with him. We had recorded a version of this album with Tom Werman, who has worked with Cheap Trick and Ted Nugent. But Interscope has the record and won’t release it. Kurt just let us be the Supersuckers. Conrad Uno and Kurt have a similar production approach.

Interestingly, many Supersuckers songs have a hard-nosed Texas rock sound.

EDDIE SPAGHETTI: We kill ‘em in Texas, too. We listen to lots of ZZ Top. Our influences are all the same. That’s not necessarily a good thing. Many bands are formed because two people with conflicting tastes work together and have this great explosion. We’re a weird aberration, like the Ramones always pretended to be. We grew up in the same neighborhood, went to the same high school (“Santa Rita High”), graduated the same year, and went to the same live shows.

What did you guys grow up listening to?

EDDIE: Early ‘80s hard rock like Ozzy, Motorhead, Iron Maiden, and Kiss – lots of metal. Through that process, we discovered punk. Of course, now I like a good punk song better than Metallica. But you’re a product of your environment. Kids today like wearing baggy pants and listening to quasi-rock. It’s killer. Every generation needs that.

Was it difficult recording straight Country tunes for the excellent Must’ve Been High?

EDDIE: I’ve always been against country-rock bands, though I’m getting to like them as I get older. I wanted my country separate from the rock. Any band that mixed them up didn’t seem transcendentally great and made me cringe. But Gram Parsons kicked ass. Steve Earle kicks ass.

How come the initial Black Supersuckers spaghetti Western blues direction of the Captain Beefheart-ian compilation track “Monkey” was never pursued again?

EDDIE: The production on that song was killer and the performance amazing. It’s haunting because the lead singer (Eric Martin) on “Monkey” died. He wanted to do Rolling Stones/ Tom Waits and we wanted to be the Ramones or AC/ DC. We were young and it wasn’t working out so we parted ways. I was struck by how good that song was because it broke up the band. We hated “Monkey” because he was blatantly flaunting drug use and there were tensions involved. I wallow in regret over his death now. If we hung in and persevered the clash of styles would have resulted in something new.

You’ve covered Ice Cube’s “Dead Homiez.” Do you think rap artists have advanced the reckless crazy lifestyle rock musicians were always known for?

EDDIE: I say kudos to that. Rap artists are having a blast. I don’t like the shooting and killing part of it. But I love the livin’ large, livin’ beyond your means, livin’ fast, dyin’ young ethic. They’re doing a great job making money, kicking ass, and screaming into a microphone.