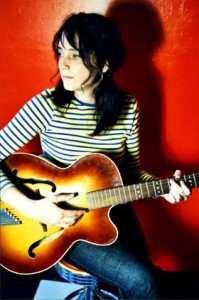

FOREWORD: In the beginning, singer-guitarist Robyn Hitchcock fronted the Soft Boys (with lead guitarist Kimberly Rew), one of the most melodically friendly bands of the late-70s Brit punk scene (alongside the Buzzcocks, and soon after, The Jam). He released a bunch of solo albums during the ‘80s and ‘90s, some accompanied by the Egyptians. A cordial guy, Hitchcock spoke to me weeks before ’99s Jewels For Sophia came out. Afterwards, the long-time cult fave did ‘03s solo acoustic turnabout, Luxor, ‘04s mod Country-folk derivation, Spooked (with roots revivalist Gillian Welch and bluegrass stylist David Rawlings), and ‘06s Ole Tarantula (with REM’s Peter Buck and Young Fresh Fellows’ Scott Mc Caughey). He returned in great form on ‘09s Goodnight Oslo.

While growing up around London in the ‘60s, singer/ songwriter Robyn Hitchcock was an average kid who enjoyed listening to British rock artists as well as their American counterparts. Self-described as “basically a late developer,” he admits to being a “very sheltered, immature kid. It took me some time to develop a sense of myself.”

“For me, ‘60s artists like Bob Dylan, who was the prime influence on most musicians, and Jimi Hendrix, were very original. Artists that were weak, their influences capsized them. But the Beatles, Kinks, Yardbirds, and the Brian Jones-era Rolling Stones through to Captain Beefheart, early Pink Floyd, and Velvet Underground, were brilliant groups. I was just twelve and I didn’t know that wouldn’t continue forever. I figured you turn on the radio and you get “See Emily Play,” “19th Nervous Breakdown,” and “Purple Haze” coming out,” Hitchcock remembers.

In the late ‘70s, Hitchcock and musical partner Kimberley Rew turned some heads fronting the Soft Boys, resulting in three absolutely classic albums, Underwater Moonlight, A Can Of Bees and Invisible Hits. In 1981, Hitchcock led a few ex-bandmates into the studio to record his first solo excursion, Black Snake Diamond Role.

After Steve Hillage (formerly of Gong) produced ‘82s throbbing, club oriented Groovy Decay, Hitchcock formed the Egyptians with ex-Soft Boys rhythm section Morris Windsor and Andy Metcalf for ‘85s upbeat Fegmania!, ‘86s introspective Element Of Light, and ‘88s charming, but inconsistent Globe Of Frogs. Following ‘90s spare, acoustic solo disc, Eye, and its lively ‘91 follow-up, Perspex Island, he re-formed the Egyptians for ‘93s underappreciated Respect, before going solo again on ‘96s lost-in-the-shuffle Moss Elixir.

Thankfully, Hitchcock’s charming Jewels For Sophia should reclaim some lost turf with its undeniably catchy fare. The wry Northwest anthem “Viva Sea-Tac,” featuring the Fastbacks’ Kurt Bloch on “She’s About A Mover”-styled organ, praises Seattle’s most innovative guitarist: “Hendrix played guitar just like an animal inside a cage/ and one day he escaped.” The fast-paced slide guitar breakdown “Nasa Clapping” and the hip shakin’ rocker “Elizabeth Jade” also energize the set. On the soft, reflective tip, lean acoustic ballad “I Feel Beautiful,” affectionate “You’ve Got A Sweet Mouth On You, Baby,” and eloquently shady “Dark Princess” reveal some of his most heartfelt sentiments.

Thankfully, Hitchcock’s charming Jewels For Sophia should reclaim some lost turf with its undeniably catchy fare. The wry Northwest anthem “Viva Sea-Tac,” featuring the Fastbacks’ Kurt Bloch on “She’s About A Mover”-styled organ, praises Seattle’s most innovative guitarist: “Hendrix played guitar just like an animal inside a cage/ and one day he escaped.” The fast-paced slide guitar breakdown “Nasa Clapping” and the hip shakin’ rocker “Elizabeth Jade” also energize the set. On the soft, reflective tip, lean acoustic ballad “I Feel Beautiful,” affectionate “You’ve Got A Sweet Mouth On You, Baby,” and eloquently shady “Dark Princess” reveal some of his most heartfelt sentiments.

Hitchcock plans to independently release outtakes from Jewels For Sophia as A Star For Bram, available at robynhitchcock.com in 2000.

You’ve become more introspective over the years.

ROBYN: It’s the inevitable mellowing out process. The process is never constant. You slowly get gentler. But you might feel quite peaceful in February and quite violent in August. Not everything I write literally happens to me, but I’ve probably imagined most of it.

You let your guard down more often.

I hope so. I didn’t mean to be guarded when I was younger. But I was probably frightened or overwhelmed by my feelings. The stuff that resonates most and rings truest are the emotional songs.

Perhaps the reason you’ve lasted so long as a vital artist is because you’re still struggling to resolve inner turmoil. I felt that way when you did Eye.

Eye had too many songs. In essence, it was good because it was written in a year during a crisis point in my life. I didn’t bother to overdub myself. I managed to let out many feelings without the help of accomplished musicians. It was very bare. The songs had to stand up by themselves. That’s why I didn’t overdo the production.

Your voice seems to have gained emotional intensity.

I think smoking cigarettes helped. (laughter) Actually, I’ve probably lost the top end of high notes. As you get older, your voice gets more authentic. My voice has more character and truth in it now. That’s built up over the last ten years. There are songs where I think I suck for trying to hide behind some other sound or trying to sound like someone else. I double tracked my voice on “If You Were A Priest” to hide any quality in my voice. So it sounds somewhere between Syd Barrett and Richard Buckner. There’s no personality in it. On “Madonna Of The Wasps,” I sound as if I’d been hit in the head with a fly swatter. Live, I sound better interpreting them now. They’ve developed some soul.

You’re as sharp witted as ever on Jewels For Sophia. The imagery and surrealism seem mindbending.

You have to approach words in a simple way. Many words are just videos for the mind. The songs should give you pictures in your head. It’s not like I’ve cunningly cloaked words like an enigma you could reach if you had a decoding book. People get confused by pictures. Sometimes the songs are very simple and don’t have many pictures in them, like “Sweet Mouth” or “I Feel Beautiful.” That’s easier.

Why weren’t the Lennonesque “Mr. Tong” and the giddy “Gene Hackman” ode listed along with Jewels For Sophia’s other song titles?

The idea was to make it seem like an afterglow. So I didn’t want to credit them. Otherwise, it’s a bit too predictable. It’s as if I’d completed my gig and you snuck upstairs to the dressing room and I was there having a drink and playing songs no one ever heard. I wanted it to feel as if the record went off somewhere at the end.

Have your acoustic songs inspired influential lo-fi artists like Smog, Palace Music, or Sebadoh?

I don’t know. I know Lou Barlow (of Sebadoh) so I should ask him. Probably the music I made with the Soft Boys up until Eye has sunk into musicians’ consciousness more so than recent stuff. I don’t know if anyone has heard what I did afterwards.

What made you decide to pursue a musical career?

My parents weren’t into music so it was an area I could colonize. My father was an artist and wrote books. So as not to compete with him I tunneled away and emerged with music. It was like breaking out of a compound and avoiding the searchlights. That’s how people are supposed to break out of prisoner war camps. They tunnel a long way out and come out in the woods somewhere. But it never works out because the tunnel always comes up short.

Would you consider writing short stories as you did with Eye’s “Glass Hotel”?

Funny you should mention that. I actually do have a novel finished, but I have to do a re-write. The plan is to finish the novel for 2001. It’s a bit gelatinous at the moment.