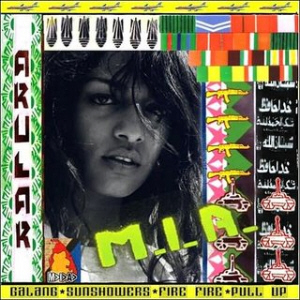

FOREWORD: M.I.A. reached the pinnacle of success in ’08 when “Paper Planes,” a nifty cut ‘n paste club track with well-placed gunshot sound affects (from her second album, Kala) made MTV and radio playlists. She received great exposure at Bonnaroo Music Festival, but told a friend of mine she was sick of being harassed during passport checks because of her fathers’ affiliation with controversial Sri Lankan freedom fighters. She’s since then taken a sabbatical and became a mother. This article originally appeared in High Times.

FOREWORD: M.I.A. reached the pinnacle of success in ’08 when “Paper Planes,” a nifty cut ‘n paste club track with well-placed gunshot sound affects (from her second album, Kala) made MTV and radio playlists. She received great exposure at Bonnaroo Music Festival, but told a friend of mine she was sick of being harassed during passport checks because of her fathers’ affiliation with controversial Sri Lankan freedom fighters. She’s since then taken a sabbatical and became a mother. This article originally appeared in High Times.

Gifted Sri Lankan refugee, M.I.A. (a.k.a. Maya Arulpragasam), faced savage bloodshed, racial tension, and hurtful injustice her entire life. But that heartbreakingly scandalous turbulence only provided serious ammunition for the foxy dark-skinned artisan. Alongside her mother, M.I.A. fled to England’s lower class council estates at her renegade father’s insistence, escaping the war-torn village of Tamil for the less violent segregationist subclass of London’s bleaker poverty-stricken Surrey section.

Graduating from prestigious Central St. Martins College, where she studied film and created graffiti art, M.I.A. soon acquired a cheap ‘80s-derived Roland TR-505 beat machine and began to cut ‘n paste minimalist dub-styled dancehall-related hip-hop while reluctantly becoming an exotic fashion plate.

M.I.A. received underground praise, then worldwide recognition for exhilarating multi-culti electroclash playground rhyme, “Galang,” the highlight of 2005’s compelling Caribbean-accented Bollywood-styled debut, Arular. Based around acid-soaked “purple haze” adulation and stocked with dazzling synthesized bleats, beeps, and bleeps, the kitsch-y “Galang” secured a knee-slapped stutter-stepped chug-a-lug pulsation merging varied global genres.

Born in the United Kingdom and raised in Sri Lanka then nearby India, M.I.A. appropriated the nickname of her protectionist father as album title fodder. A militant guerrilla battling majority Sinhalese Buddhists as leader of the autonomous Eelam Revolutionary Organization, he thereafter aligned with the larger secessionist Tamil Tigers sect of northern Sri Lanka, fighting for equal rights while resisting unfavorable federal settlements oppressing his native Hindu minority for decades. Resorting to roadside suicide bombings and other violent acts, their vicious terrorist tactics counteract the inequity of heavy-handed government enslavement.

Unlike radical Islam, the Tamil Tigers fight for sovereignty and independence, not tyrannical subjugation a la wrongheaded fundamentalist gangland murderers in the Taliban. However, the controversial Tigers broke a 2002 cease-fire agreement, launching a few deadly air attacks on the military from M.I.A.’s hometown of Jaffna, blowing up a civilian bus, and bombing Sri Lanka capitol, Colombo, in 2007 alone.

“I feel sad the Sri Lankans that make it out can’t talk about (the troubles). There’s two million military soldiers against 5,000 Tigers, which is now only 2,000. Something’s seriously wrong,” M.I.A. insists. “The week I got my graduate certificate from art school, someone said my cousin, whom I’d copied off in school, was dead. It was devastating. In England, I was able to live a different life. I can complain about stupid shit like Playstation and my shoes in London. But I wanted to make a connection between the apathy I was feeling in England and what (my peers) in Sri Lanka go through. If you shoot to kill people wearing black, a supposed terrorist color, on suspicion, the murderer doesn’t need to be brought in on. You weren’t allowed to wear khakis, leopard-tiger prints, Puma shirts.”

M.I.A. attempted to enlighten the outside world about the subjugation and repression witnessed via a firsthand documentary, but fearful ultraconservatives lynched the anticipated film while absurdly aligning her with terrorist uproar.

“When I went back they said my cousin was a vegetable in a refugee camp. Some said he was married to a Sinhalese girl and defected. I found that every Tamil family had those stories. You never find the body and it’s hard to exorcise from your life,” she admits. “Under oppression, you have no future. I was constantly harassed by police. I had to register at police stations just to get a hotel room. Tamil people are lined up like herds of animals in 100-degree heat in dirt. The army empties their goods into mud and the babies are all gonna be dead by age five. They were disposable. It felt horrible. The Tamils are banned from census reports. The government could wipe out the whole race and there’d be no account. If you’re talking about terrorists, the group is as good or bad as the government they’re struggling against.”

M.I.A.’s combative Cockney-cadenced lyrical discontent contrasts Arular’s primal upbeat sway and crackling tropical riddims. Sure-handed Philadelphia DJ, Diplo, her old flame, provides a few stomping beats and talented collaborators. Swarming robotic reggaeton rumble, “Bingo,” tribal quick-spit protocol, “Sunshowers,” and redemptive jump-roped woofer-blasting alarm, “Fire Fire,” are armed and extremely dangerous missives. On “Bucky Done Gun,” faux-trumpets anticipate a bloody skirmish. Despite Arular’s overwhelmingly confrontational theme, static-y club-banging anthem, “Pull Up The People,” seeks uplifting proletarian liberation. Sirens, laser zaps, steel drums, traps, toms, and tape-looped samples gird the elementary arrangements. A tone-deaf wild child with no prior musical skills, the scrappily resourceful M.I.A. startlingly became a universal superstar.

“What I did with Arular was a test with a bunch of questions that came from all angles – the media, immigration, the government, certain magazines, and television stations. I had to have consequences and side affects,” she explains. “Sri Lankan Sinhalese rioted at venues where I performed. They tried boycotting. I got hate mail. I’m not doing this to be ignorant and precious or angry and negative. It’s interesting to see the edges of these problems. I’ve seen Sri Lankan monks killing people and children. How do you allow it to go on? I went to British, Christian, and Hindu schools. The army would come down to the Tamil convent (I attended), put guns through holes in the windows and shoot. We were trained to dive under the table or run next door to English schools that wouldn’t get shot. It was a bullying exploitation.”

M.I.A. initially found her groove after finishing college while vacationing on tiny Caribbean island, Bequia, where Gospel music and Diwali jungle rhythms piqued her interest. She had no love for pop and dismissed punk because of its skinhead association, but started assimilating her newfound Carib influences with the underground rap infiltrating Surrey’s poorest populace.

“I went to Bequia with a friend who wanted to get away from hard times,” she recalls. “I started going out to this chicken shed with a sound system. You buy rum through a hatch and dance in the street. They convinced me to come to church where people sing so amazingly. But I couldn’t clap along to hallelujah. I was out of rhythm. Someone said, ‘What happened to Jesus? I saw you dancing last night and you were totally fine.’ They stopped the service and taught me to clap in time. It was embarrassing.”

Then, she got stoned at night and wrote swaggering rogue flaunt, “M.I.A.,” procuring the appellation as stage name and dedicating it to her former London gang association with Missing In Action.

“I’d never smoked weed,” she admits. “At the time, it helped kick-start and focus my obsession with music. But it’s not productive if you’re completely reliant on it. I’m constant – the same high or not.”

M.I.A. adds a small disclaimer, “Getting high is like losing control and these days women have too much on their plate raising kids, working, looking good, being on MySpace.”

Then again, she’s onboard for marijuana reform and legalization.

“Going to the Caribbean the first time, it was like Sri Lanka without the war and ugliness -real beautiful and natural. People were chill, no stress. If weed makes people passive, content, and happy, it’s fine. Of course, America has the best weed. In England, it’s garbage. No one takes time to cultivate the land. Besides, the sunshine’s better in America.” Furthermore, she claims, “I did a show on mushrooms in Japan. Thought it was the best show I’d ever done, even if it wasn’t the case. It was amazing. I felt like laughing the whole time as lights were going around and it got real trippy. Everything felt like it was going in slow motion.”

Dropping much of the political rhetoric on her equally fine ’07 follow-up, Kala (named in honor of her mother), M.I.A. still effectively sods Indian-induced hip-hop culture with British grime, a vogue urban two-step garage styling Dizzee Rascal and Wiley made famous. Jumpy Jamaican jostle “Hussel,” beeping nursery-rhymed romp “Boyz,” and clanging rampage “Bamboo Banga” (which hijacks Jonathan Richman’s classic cruisin’ rambler “Roadrunner”), deal more with the politics of dancing than war.

Dropping much of the political rhetoric on her equally fine ’07 follow-up, Kala (named in honor of her mother), M.I.A. still effectively sods Indian-induced hip-hop culture with British grime, a vogue urban two-step garage styling Dizzee Rascal and Wiley made famous. Jumpy Jamaican jostle “Hussel,” beeping nursery-rhymed romp “Boyz,” and clanging rampage “Bamboo Banga” (which hijacks Jonathan Richman’s classic cruisin’ rambler “Roadrunner”), deal more with the politics of dancing than war.

M.I.A. offers, “Arular was immersed in politics. It was on the street corner and t.v. I was outraged. This time, I had to work out where I was. Did I wanna be a pop star or an artist? There are so many options. That’s the downside. I had to find a place that gave me more space to grow. People are wrong to judge me as someone who’s shoving a manifesto in people’s faces and say ‘live like this.’ We all saw Saddam Hussien hung on U-Tube. People have seen how that situation panned out. I thought it was important to teach people to find balance in their life. Find happiness in what’s around you. I’m on the verge of being a super-Americanized version of a musician, but I could’ve stayed humble, got married, had kids, and say I’ve done it once, why try again?”

Perhaps the forthcoming apocalypse could be put on hold, as the carousing Kala truly gets the party going in a ceremoniously footloose manner. She celebrates ecstasy-laced rave culture on the bustling “XR2,” cunningly inquiring ‘where were you in ‘92/ took a pill/ had a good time.’

“An XR2’s a shitty hatchback Ford and the easiest car to break into. All the kids I hung out with back then were in little gangs that fought. One gang had an XR2,” she says. “We were the first ones to break out of the stupid-ness and the violence and started going out to parties and raving. We were more into music, dancing, fashion.”

This type of bohemian brevity won’t solve the planet’s staggering tribulations, but its escapism is absolutely addictive.

Though she may remain skeptical about with the Tamil Tigers fierce fanatical intimidation, M.I.A. understands how difficult and tricky the Sri Lanka situation still is, especially since juvenile labor and child soldiers continue to exist.

She concludes, “My work constantly opens minds for debate on the Tamil Tigers. What makes good and evil? I felt uncomfortable broaching it. People won’t give me the benefit of doubt. If you’re a citizen and get shot or bombed, you should be able to tell anyone if you have a microphone in your face. Politics of war changed the course of my life. I’m eating a burger talking to you, but I could’ve been in Sri Lanka with eight kids running an electric shop selling t.v.’s and baking cakes for neighbors. But I’ve come this far. If you care about the issue of child soldiers, look towards Africa. Every other soldier’s a child. Every country has these rebels popping up. The Brits fucked up the Tamils, who were smart, educated, middle class civilians. When the Brits gave power to the majority Sinhalese, they made the Tamils’ laborers and farmers. In Jaffna, we had electricity. Eelam, my father’s group, came out of that. They’d been abroad, knew international politics, theology, and had a manifesto. They were into non-violent protest. But the Tigers wouldn’t have it. Their kids, moms, and grandparents were butchered. They had no arms or ammunition. They had sticks, stones, and knives, objects used to cut fish. My dad’s group was outnumbered. That’s how the Tigers became the biggest representatives of the Sri Lankan struggle.”

Happily, M.I.A. has overcome many arduously complex and frightening circumstances to develop into one of the choicest young artists in contemporary music. She’s candid, intelligent, liberated, opinionated, strong-headed, and raw – a proven commodity in a wearily wired world.

FOREWORD: I remember being in west Florida’s resort peninsula, St. Joseph’s, cleaning freshly caught fish with my friend Doug at a waterfront house he rented, when Del The Funky Homosapien’s quick-spit rap quip, “Mistadabolina,” came on the radio. Integrating De La Soul’s jazzy hip-hop/ soul sass with the minimalist rap attack of Run DMC, Del could’ve set the world on fire if the mainstream was privy to him at the start. Instead, he has led a subterranean existence below dozens of trendier flash-in-the pan stylists, blowing off the whole gangsta scene from the start. However, he has outlasted nearly all his peers and continues to make interesting music. I got to hang with Del in May, ’08, with my good friends from High Times. This article originally appeared in High Times.

“We used MDMA when ecstasy was pure,” says Del in his slurry guttural drawl. “But it wasn’t poppin’ like now in the Bay Area. It’s their whole mantra. I like to keep my mind on a certain level before a show. I don’t want people seeing me eking out. If I’m recording, I’d be too lit going off in a corner talking to someone trying to keep from flying off somewhere.”

“We used MDMA when ecstasy was pure,” says Del in his slurry guttural drawl. “But it wasn’t poppin’ like now in the Bay Area. It’s their whole mantra. I like to keep my mind on a certain level before a show. I don’t want people seeing me eking out. If I’m recording, I’d be too lit going off in a corner talking to someone trying to keep from flying off somewhere.”