FOREWORD: Given adulation by avid indie heads, but never properly recognized by aboveground mainstream pop drips, Imperial Teen was at the top of their game when I interviewed Roddy Buttom and Jone Stebbins to promote ‘02s tantalizing On. But they took a protracted five-year sabbatical before the less interesting, introspectively mature The Hair The TV The Baby And The Band finally arrived. During that time, Roddy composed film and t.v. music. Jone became a hairstylist. Lynn Perko got married and had kids, and Will Schwartz started his own band, Hey Willpower. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Imperial Teen delivers infectious California pop that sticks in your head like a sexually charged sunny afternoon daydream. The alluring warmth of the sumptuous harmonies by guitarist Roddy Buttom (ex-Faith No More keyboardist), bassist Jone Stebbins, keyboardist Will Schwartz, and percussionist Lynn Perko caress leisurely cheerful post-New Wave euphoria.

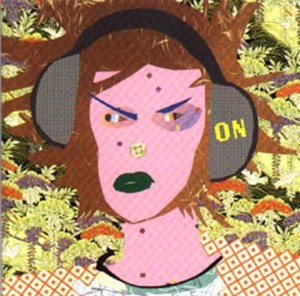

For their third full-length, On (Merge Records), the catchy quartet expand moods, textures, and rhythmic design, contrasting wispy illuminations such as the sublime “Captain” and the slow burning lullaby “Undone” with the electronic indie pop of “Million $ Man” and the lascivious “Teacher’s Pet.”

Surrealistic anthem “The First” repeats an uplifting mantra gleefully, recalling Velvet Underground’s “Pale Blue Eyes” and David Bowie’s “Heroes” in its resplendent glow. But it’s the triumphant opening punch of irresistible melodic treasures “Ivanka,” the bubblegum-induced “Baby” (somewhat reminiscent of T. Rex’s “Hot Love”), and the insouciant psychedelic warbler “Sugar” that initially suck the listener in.

Surrealistic anthem “The First” repeats an uplifting mantra gleefully, recalling Velvet Underground’s “Pale Blue Eyes” and David Bowie’s “Heroes” in its resplendent glow. But it’s the triumphant opening punch of irresistible melodic treasures “Ivanka,” the bubblegum-induced “Baby” (somewhat reminiscent of T. Rex’s “Hot Love”), and the insouciant psychedelic warbler “Sugar” that initially suck the listener in.

Formed in ’94, Imperial Teen soon found an audience with the engaging debut, Seasick. Thanks to MTV exposure, the insinuating “Yoo Hoo” (featured prominently on the Jawbreaker soundtrack) gained the attention of mainstream America and gave ‘98s impressive What Is Not To Love a leg up. However their record label at the time, London Records, was being tossed around like a French whore, ruining the much-needed momentum for further radio penetration.

Nevertheless, the co-ed combo stumbled ‘On’ and now find themselves on the undercard for the current tour by the re-formed Breeders at Bowery Ballroom.

What were some of your early musical influences?

RODDY: More than music, my mother was an influence. We played piano together. I got into Ragtime at an early age. Afterwards, I liked Elton John and pop. Then, I got into punk, moved to San Francisco, took a lot of drugs, got influenced by my surroundings, and began experimenting.

JONE: When I was younger, I didn’t get into Led Zeppelin until I moved to Frisco. My parents listened to Country and Big Band music. I found punk when I was 13. I didn’t listen to Classic Rock ‘til my twenties.

Roddy, was it difficult changing direction from being keyboardist in metal-edged Faith No More to co-leader in indie pop band Imperial Teen?

RODDY: Faith No More was very democratic. Everyone was involved. I was younger and there was more of a sentiment of where we were at that time, pushing buttons and getting in people’s faces. I’d moved from home to a strange, weird city, and went in that direction. Now, singing intrigues me more. There’s a lot to be said for the word, topic, and subject matter.

On utilizes more moods and textures than the past albums.

RODDY: Probably so. We got more studio-oriented. Our first batch of songs didn’t even use distortion pedals. They were just as we wrote them. By the second album, we had more time to get into the studio aspect. We’ve reached some sort of middle ground now.

I was particularly intrigued by the simple, melodic “Mr. & Mrs.”

RODDY: Everything we start writing begins in the studio. We were playing around with keyboards and drum machines. That’s about people we know in San Francisco. It was written during a nostalgic time when San Francisco was going through that weird dot com thing and its affect on commerce. It felt like a city was burning down.

I like the student-teacher fuck fable, “Teacher’s Pet.”

RODDY: I like the story of a person on the way up and the other on the way out. That’s what I tried to capture. “Lipstick” on the previous record, has the same vibe.

Many of your songs have a playful sexual nature.

RODDY: I hope so. That’s always the most fascinating and it pushes people’s buttons. I get more into specifics while Will gets caught in vague pictures.

JONE: Sex is an important part of human existence and becomes a factor in writing songs about situations in your life. You could read whatever you want into the lyrics.

Have your harmonies become more complex? Do you appreciate ‘60s vocal groups such as the Four Tops, Four Seasons, and Beach Boys?

RODDY: People regard us more like the Mamas & Papas as a singing group. As far as emotions go lyrically, I think that’s more important than where things go instrumentally. I’ve always related to harmonies.

Was “Ivanka” the opening track because each member gets a chance to sing lead?

JONE: It’s one of our older songs. When What Is Not To Love was finished, we had “Ivanka” done. So it’s super familiar and shows the essence of our band summed up in one little neat song.

Which pop bands currently knock you out?

RODDY: I’ve always loved the Breeders. They capture the moment with their songwriting and harmonies. There’s some San Francisco bands I like – the Aislers Sect and Track Star.

JONE: I’m listening to old ‘20s music. I have a ukulele project I’m working on half-assed with a few friends. We had disbanded Uncle Dickie & His Ukel-Ladies, but after the Kristin Dunst movie, Cat’s Meow, which featured ukulele music I like, it made me want to do “5’2 Eyes Of Blue.” But I’m not attracted to Hawaiian ukulele music.

Does Imperial Teen feel scandalously underappreciated? After MTV exposed “Yoo Hoo,” I felt you should have set the world afire.

RODDY: It seemed things were going that way. But Polygram’s merger screwed us up. We got caught in between. Only bands that are so safe and take no risks were a sure bet.

JONE: Radio in San Francisco is real bad. If those songs they’re playing are popular, I don’t wanna be played next to them. You’d thing there’d be an actual cutting edge commercial station considering the city’s history. There’s college station KUSF and Berkeley has KALX, but I think they share the same airwave signal.

-John Fortunato