FOREWORD: New York City’s scrappily experimental Jazz-funk trio, Medeski Martin & Wood, inventively enjoined hip-hop rhythms and jam band sauntering to its eclectic musical stew. When I caught up to them at Manhattan’s enormous Hammerstein Ballroom in ‘97, I saw one overdosed hippie, two naked large-nippled girls, and drank three Heineken beers as they played to a capacity crowd. They’ve continued to release many live, acoustic, or studio LP’s since. MMW’s members have offered their services to many artists, including Chris Whitley, John Scofield, North Mississippi All Stars, and Phish head, Trey Anastasio. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

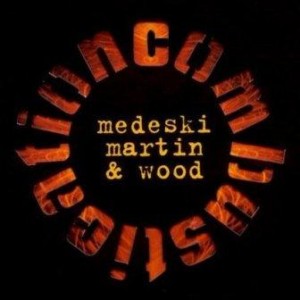

Taking the title of their newest disc, Combustication, from public TV personality Dr. Julius Sumner Miller, downtown New York City improvisationalists Medeski Martin & Wood prove great camaraderie and intuitiveness equals a successful democratic fusion of jazz and funk. Meeting at avant-garde Mecca, the Knitting Factory, around 1990, keyboardist John Medski, bassist Chris Wood, and drummer Billy Martin share a love for provocatively daring instrumentals.

MMW’s fifth album, Shack-Man, gained respect for its abstract post-bop acid Jazz amongst post-modern prog-rock fans and intelligent indie rockers alike. Those who really wish to explore uncharted territory are immediately directed to the trio’s self-released Farmer’s Reserve, a straight-up, unedited improv experiment available on the internet.

Following the unlikely success of Shack-Man, the more stylistically diversified Combustication also attempts to broaden the palette of the combo’s avid fans. Guest turntablist DJ Logic valiantly adds scratches, electronic textures, and sampled loops to the organic mix.

Keeping busy on the side as a studio hand, Medeski recently produced the new Dirty Dozen Brass Band album, wrote Dave Amaran’s musical score dedicated to beat poet Jack Kerouac, and composed a traditional organ piece with guitarist Marc Ribot for a Windham Hill sampler. He has previously played with the Lounge Lizards, Either/Orchestra, and the late-great bassist Jaco Pastorius. That’s just the tip of the iceberg.

What type of music did you listen to as a kid?

JOHN: At age five I first started playing Classical music. Then I got into playing old Jazz and pop tunes from the ‘40a and ‘50s. When I was eleven, my neighbor’s older brother played me Oscar Peterson and I realized there was a whole other way of doing this stuff. That’s when I began getting into Jazz. I attended the New England Conservatory of Music part time while I worked for five years. I switched over to more improvisational music after that when I bagged Classical. I didn’t see the point of going to school for Jazz when you could learn privately and go out and play. I’m not a big fan of school.

In comparing Combustication to the previous set, Shack-Man, I’d say it’s less funk and more expansive.

JOHN: I think Combustication is more of a studio record. It’s more expansive. It might be more Jazz in feeling. But it’s more funk and hip-hop the way it’s mixed. It’s a different combination of what we’re about: grooves and improvisation. Shack-Man’s very live in terms of recording style.

Some fans claim Medeski Martin & Wood are avant-garde-ish, but your music is easier to approach and more accessible.

JOHN: I have no idea. Avant-garde music is an inspiration, but we play more and more grooves. We love groove music. Many of the current avant-garde artists have great spirit and are expressing themselves well.

I find your melodies easier to follow than Ornette Coleman’s or Henry Threadgill’s.

JOHN: Yeah. I guess. Actually, we don’t dwell on catchy, strong melodies. Sometimes we are criticized for that. In general, the vibe comes from New Orleans funk as much as avant-garde.

And now you’re signed to legendary Jazz laberl, Blue Note. How’d that come about?

JOHN: They’re great. They treat us good and put no artistic pressure on us. Their approach is very hands-off artistically. And it’s not working out for them business-wise, they simply drop you.

Much like Booker T & the MG’s during the ‘60s, MMW could probably make a secondary career backing other intelligent likeminded musicians.

JOHN: Yeah. We do play on a couple peoples’ records. We get calls from time to time to do that. We did John Scofield’s Au Go Go record and singer Oren Bloedow’s record. Chris Wood and I recently played with Mark Anthony Thompson on his Chocolate Genius LP. I love playing all kinds of music with all types of people. As for our band, it’s very democratic. Like Bill Evans Trio, who started it, we have a bass, drums, and piano lineup.

Plus, turntablist DJ Logic adds electronic enhancement and weird sounds to Combustication.

JOHN: He fits in the cracks. Not a lot of DJ’s could play live. You’d think it would be an obvious thing but very few people could do it, especially when you’re improvising around it. We take a lot of left turns and he stays right there with us. He fits into what we do more than just about anyone ever has. He adds elements without changing our direction. He’s from the Bronx and we met him playing with Vernon Reid. We called him up to do a few Shack-Man parties that we did at the Knitting Facoty and that was it.

You completely reconstruct Sly & The Family Stone’s “Everyday People.” Your version has an ethereal Gospel feel.

JOHN: I love that song. Name a better composer than Sly. He’s up there with anybody. We’ve reinterpreted John Coltrane, Thelonius Monk, King Sunny Ade. We like to pay homage to great musicians that inspire us. We started doing that tune a while back. It felt good to play “Everyday People” the way we did.