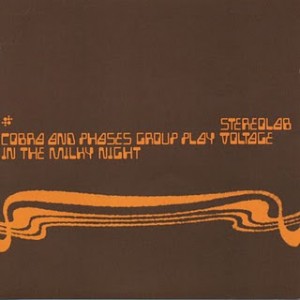

FOREWORD: Arguably the finest purveyors of easy listening ‘90s lounge-core, London’s stimulatingly minimalist combo, Stereolab, mixed gauzy ‘60s-styled French noir and classy ‘50s cocktail music with Teutonic kraut-rock machinations in a uniquely fun way.

The title of ’93 EP, Space Age Batchelor Pad Music, may describe their style best. Leaving behind a long trail of LP’s, EP’s, and singles, Stereolab really hit stride with the quick-to-follow prog-dipped phantasm, Transient Random Noise Bursts With Announcements.

‘96s Emperor Tomato Ketchup was even tighter and more focused. After ‘97s Dots And Loops, I caught up to French-bred singer, Laetitia Sadler, to promote ‘99s Cobra and Phases Group Play Voltage In The Milky Night (and found out she really doesn’t care for lazy French people).

After Cobra, Stereolab were steadily assured but less venturesome. ‘01s Sound-Dust was OK and ‘04s reflective Margerine Eclipse was too. But there was a large four-year gap to ‘08s Chemical Chords. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Growing more adventurous and experimental without losing their passion for leisurely romantic melodies, Stereolab continue to craft warm, intimate meditations of lush grandeur, pastoral pleasure, and modern sophistication.

Dropping some of the kitsch-y exotica for a more Jazz-affected feel, Cobra And Phases Group Play Voltage In The Milky Night proficiently expands into new directions, increasing the London-based collectives’ versatility and range.

At its most revealing, Cobra captures the wistful moodiness of ‘60s lounge-core alongside the post-bop illuminations of guest cornet player Rob Mazurek’s Isotope 217. Like a simplified free Jazz excursion, “Fuses” unexpectedly opens the set, gently pushed aside by the truly absorbing “People Do It All The Time,” a more natural sounding smooth pop ballad textured by soft aquatic nuances.

At its most revealing, Cobra captures the wistful moodiness of ‘60s lounge-core alongside the post-bop illuminations of guest cornet player Rob Mazurek’s Isotope 217. Like a simplified free Jazz excursion, “Fuses” unexpectedly opens the set, gently pushed aside by the truly absorbing “People Do It All The Time,” a more natural sounding smooth pop ballad textured by soft aquatic nuances.

To counter the jazzy bass groove of “Free Design,” “Blips Drips and Strips” goes adrift with melodic vibraphone and Sergio Mendes-like lounge-pop effervescence. Later in the program, “Puncture In The Radak Permutation” slips from staccato piano espionage theme to vibe-spindling orchestral string excursion.

As usual, founding members Tim Ganes and Laetitia Sadler (whose casually alluring French-accented vocal swirls give Stereolab its signature sound) surround themselves with prominent collaborators. Tortoise percussionist John McEntire, High Llamas harpsichordist-clavinetist Sean O’Hagan (both of whom helped out on previous endeavor, Dots And Loops), and experimental Chi-town multi-instrumentalist Jim O’Rourke delve deep into Stereolab’s ever-changing muse by providing organic luster and blissful tones.

I spoke to the lovely, talented chanteuse, Laetitia Sadler, via phone while she was in sunny Tucson, Arizona during November ‘99.

What was it like growing up in France?

What was it like growing up in France?

LAETITIA: I moved around a lot. So I wasn’t rooted anywhere. From ages 10 to 12, I lived in upstate New York and had a view of the world most people didn’t have. That’s what prompted me to leave France. When I came back from the States, I found refuge in music. I’d rather listen to music than chatter with friends. At 16, I wanted to play in a band, but I found a lot of bull shitters lacking talent. I went to London as an au pair and figured if it was going to happen it’d happen there.

I met Tim indirectly in France when he was in a band called McCarthy. They were ahead of their time. They were quite known among the underground when being independent meant something in 1985, following the aftermath of punk. Some bands that were similar to McCarthy even found broad success. When they broke up, Tim wanted to make unique music. He set out to do it. It wasn’t easy, but if you search long enough, you get there. I wanted to write about things that mattered to me and also raised a lot of questions. We did that with Stereolab. We’ll never entirely be reached, but we’ve carried on for nine years so far.

Were you influenced by Serge Gainsbourg’s brilliant ‘60s French lounge pop?

LAETITIA: I think Stereolab’s melodic aspect is fundamental. French pop in general – Francois Hardy and string arranger Vanier, as well as Serge, inspired us. Vanier’s arrangements were very moving and melodic. Melodies are very powerful. They can haunt a million people because they’re so strong.

Cobra seems to be Stereolab’s most Jazz-influenced set. How does it compare to your previous album, Dots And Loops?

LAETITIA: It’s more likable than Dots And Loops. It has more air in it and some relief. I find it stifling. But all the tracks have good qualities. On Cobra, the melodies are meant to be sung rather than our vocals being used as mere instruments. The songs are more fun to sing. When we started playing them at shows in the spring people were immediately taken by the songs. On first listen you’re not gonna grasp it all. I didn’t.

Do you feel Stereolab is responsible for exposing the thriving ambient-lounge scene?

LAETITIA: Yeah. We were doing stuff at a point when no one else thought of doing it. Maybe we were an incentive for some artists to do something different. For others, we weren’t. I know people in Paris, England, America, and Tokyo listened to the same sort of muzak and found it inspiring. They wanted to integrate it into their music. They thought, ‘I did it first. They all ripped me off!’ (laughter) As for Stereolab, the magic lies in John (McEntire), Jim (O’Rourke), Mouse On Mars, Sean O’Hagan of the High Llamas and other collaborators. Sean’s put such an impression on our music. We’re made up of many elements. It’s an amalgamation of ideas.

Did you record Cobra in Chicago because it’s the home of Tortoise collaborator John McEntire?

LAETITIA: Chicago is like a lover you could never live with, ever. But you toy around with the idea and fantasize about it.

People say that about Paris, France.

LAETITIA: I don’t have any romantic notions about France anymore because there’s lots of social tension. People are unhappy and grumpy. There’s such a malaise I’ve never seen in any other people. I’ve met Americans who hate America because of its society and government being brutal and violent. But the Americans see through this and have certain values. The French have a profound hatred of the French, And I have that,. I had to get the hell out. There’s no real progress there. It’s just talk, talk, talk, You can only have fun when you start doing things instead of just talking about it. They’re good at being academic and have a realm of ideas, but they never take action., Although some people are the exception.

I’m amazed with the large amount of material Stereolab has released thus far.

LAETITIA: Other bands are just lazy. We could put out much more, but we have to tour. Plus, Tim and I have to spend time with our child. We built our own cellar studio in London recently. Soon we could be self-sufficient.

Who would you like to collaborate with in the future?

LAETITIA: There’s this guy, Richard Devine, who’s from Miami and runs a small label that releases leftfield techno, jungle, and electronic music. It would be nice to collaborate with him. He’s making music I feel is new and imaginative without borrowing from the past or re-modernizing.