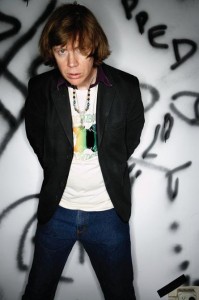

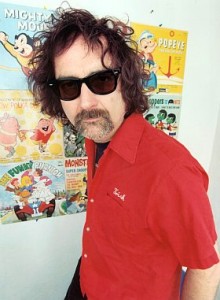

FOREWORD: Mr. T Experience is the brainchild of Frank Portman, a mainstay of Berkeley’s famed late’90s Gilman Street scene. After a five-year layoff, MTX came back strong with ‘04s Yesterday Rules. At that time I spent a few hours eating, drinking and talking with Frank and his female publicist at Brooklyn’s North 6 club – prior to his show. Nice guy. In ’06, Portman’s first novel, King Dork, arrived. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Before Green Day and Rancid discovered gold in San Francisco, Mr. T Experience were slowly developing Gilman Street’s vital underground scene across the bay in nearby Berkeley. Founded by Dr. Frank (Portman) and ex-member Jon von, the perky combo originally gave fidgety tongue-in-cheek romanticism and disparagingly wry humor limited indie pop credibility while hair metal claimed mid-‘80s airwaves.

“When we started, there were no local bands that weren’t Reagan-oriented hardcore rock,” Dr. Frank insists as he swigs a pre-gig beer in my Odyssey. Still going strong despite two breakups, a misunderstood ’99 misstep entitled Alcatraz, and a hard-to-find solo follow-up, MTX (Mr. T’s abbreviated handle) hang in there with ‘04s resounding comeback Yesterday Rules.

Oft times the brunt of cruel anti-pop jokes at their beginning stages, MTX struggled to gain serious attention before paving the way for Operation Ivy (Tim Armstrong’s pre-Rancid gang) and Sweet Children (Billie Joe Armstrong’s pre-Green Day crew).

“At early Gilman shows, a hodgepodge of weirdos would open for national acts. One of our first shows was Nomeansno. But hardcore metallurgists MDC and Attitude Adjustment were in the mix and they’d make fun of us so we’d have a terrible time,” Dr. Frank recalls. “They’d go, ‘You’re that la-la-la band.’ People say we started the pop-punk trend, which I don’t think is all that accurate. We couldn’t get on metal bills, so we put shows on at pizza places, gradually hooking up with Maximum Rock And Roll to start the Gilman club.”

Soon the East Bay scene changed as prog-metal lost traction and pop-punk won out. Green Day attracted major notice. The defunct Operation Ivy became a genuine mass cultural phenomenon. Eventually, do-it-yourself bands became hot show biz prospects, reeking revenge when The Offspring blew up in ‘95.

But Dr. Frank admits the historic early Gilman scene was overvalued and undernourished just as the ’77 Brit-punk explosion he watched firsthand had been.

“I remember all those early shows being lame, poorly attended, and pathetic. The audience wasn’t paying attention and Tim Yohannon of Maximum Rock And Roll had a philosophy to go along with his Communist rhetoric that bands should be taught they’re not so special. You’d have to clean bathrooms – which we stopped doing because it was hard enough being in a band,” he declares. “Kids now think that was the golden age, but I tell them it wasn’t wonderful. Most shows had only 50 people. We just couldn’t play anywhere else. It’s still going on now.”

Incredibly, at age 14 Dr. Frank attended the Sex Pistols last US show in ‘78, where Johnny Rotten made his famous ‘Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?’ comment. He remembers that spectacle and an early Clash show being lousily planned, awkwardly handled, and audibly awful.

Clarifies Dr. Frank, “When I think back at those shows, I can’t remember how it sounded because I was overwhelmed. My ears were ringing for the next year. My friend Mike and I took the bus to the city and saw The Clash at Kezar Stadium in Golden Gate Park. That show sounded like a tangle of feedback and noise. You couldn’t make out songs, but I thought it was the greatest thing I’d seen. Everything The Clash did then you try to avoid. You want everyone playing at the same time and be able to distinguish guitar from vocals and bass. It was a mess.”

Inexplicably, Dr. Frank alleges punk hadn’t yet been established in the States and the Sex Pistols audience was full of freaky longhaired tie-dyed hippies that’d frequent Bill Graham concerts.

“Those bands misunderstood America,” he smirks. “They booked clubs in working class areas thinking there was a street music scene like in England. But our working class weren’t punks. So it was cool and stupid at the same time. They were selling cream pies with broken glass that you were supposed to throw at the stage. I bought all this Communist propaganda after The Clash show and my father said, ‘You might want to give a critical eye to this stuff.’”

Wow! I’d thought the most exciting historical fact about Dr. Frank was his whore lord grandfather. Speaking of familial ties, his now-deceased father restored Frisco’s famed Mission Delores (its graveyard visited in Vertigo) and built Mission San Jose in the South Bay from the ground up. A general contractor with Catholic beliefs, he turned pre-teen Frank onto folk beatniks the Kingston Trio and Limeliters. But of foremost interest then were his parents show tune albums. That changed when a college bound aunt introduced Frank to punk and he soon bought English new wave by the 101ers, Motorhead, and the Undertones while picking up New Musical Express. Though various old girlfriends depleted a solid record collection, the priceless Chiswick recordings remain in his domain.

“At high school, I tried to adopt something that’d completely confuse classmates. There’s a lot of energy and power in that. I see that in our younger fans. MTX are like a little club they belong to and all other people are idiots,” he says with a grin.

“At high school, I tried to adopt something that’d completely confuse classmates. There’s a lot of energy and power in that. I see that in our younger fans. MTX are like a little club they belong to and all other people are idiots,” he says with a grin.

Though embarrassingly juvenile, MTX’s foretelling ’86 debut, Everybody’s Entitled To Their Own Opinion, was recorded cheaply in one day by lowball producer Kevin Army (who’d twist knobs for initial developing Lookout! acts and still remains on board for Dr. Frank 18 years hence). Despite a poor budget, it captured the amateurish potential, earnest youthfulness, and jocular novelties channeled through slowly developing neophytes.

Following ‘92s zesty Milk Milk Lemonade, which featured MTX’s most skilled performances yet, the band broke up, re-organizing sans Jon von for ‘93s “Gun Crazy” EP and the confectionery Our Bodies, Ourselves. ‘95s engagingly candy-coated …And The Women Who Loved Them refined the truncated trio’s approach to loud, festive three-chord delirium further advanced by ‘97s even better Revenge Is Sweet And So Are You. Then, the consistently improving MTX delivered the harder-edged bubblegum-punk masterpiece, Love Is Dead. Led by the catchy shouted singalong “Ba Ba Ba Ba Ba” – still a concert staple – they were back in fine form with more economical tunes, better stylistically developed material, and sharper jovial wit.

However, ‘99s ill fated Alcatraz tainted Dr. Frank’s reputation amongst some long-time fans. A commercial failure radically different from its predecessors, MTX had hoped to challenge their audience with raw tracks.

He inquires, “I got together with Kevin (Army), told him I wanted the sound to be different to distinguish it. So I had these lo-fi demos and found you could make music that’s rocking and communicate appealing emotions when you back off the thick layer of generic punk guitar noise. So Alcatraz was my statement of independence to build the band from the ground level. We used different guitar levels on each song and took great pains to let the sonic depth equal the songwriting depth. It split our fans in two. That pissed me off, led to a solo record, then 9-11 derailed things practically, financially, and psychologically. I obsessed on international politics, which detracted from the music. That’s what took so long to do another record.”

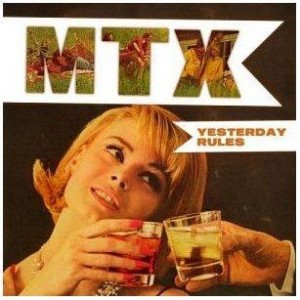

Breaking in new players, MTX triumphantly return as a quartet with the enthusiastically nostalgic Yesterday Rules. Its girl-with-martini cover art beckons mid-‘60s discotheque nirvana, perhaps invoking a nifty Laugh-In appeal.

The upbeat neo-psychedelic charmer “Boyfriend Box” spreads sunshine nipping at the Monkees closing t.v. theme, “I Wanna Be Free.” A winsome bounce escorts the otherwise frustrated “Oh Just Have Some Faith In Me” and the impulsively discontent “Fucked Up On Life,” which recalls early Elvis Costello or Graham Parker with its quirky mid-tempo melodicism. The footstompin’ “Shining” rocks hardest of all.

But most memorably, the cleverly catchy acoustic strummer “Institutionalized Misogyny” explores love-hate politics and seems adapted from Appalachian Country ode “Rocky Top.”

“I’ll seem like a dork, but casting that song along the lines of traditional folk was done purposely to underscore the quaint homey attitude sometimes ridiculed, but it branches off into a ‘60s soft pop angle at the bridge. The title was intriguing because you can’t imagine how it’d be a song,” Dr. Frank confides.

When I mention the loopy “Everybody Knows Your Crying” would work as a George Jones tearjerker, he agrees. “George Jones’ songs are genuinely moving, make you wanna cry, and then they’re instantly a part of you: “The Race Is On.” “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” that one is a puzzle or little riddle. When you realize what it says, it hits you like a godly thing, a taste from beyond.”

At Brooklyn club North 6, tidily thin Dr. Frank, wearing a brown leather jacket and slinging a cherry wood guitar, lets his jittery left leg drive the beat as he leans slightly towards the mike to deliver Yesterday Rules highlights and frosty crowd favorites in a honeyed baritone. Kids pogo to “Ba Ba Ba Ba Ba” and chant along during three acoustic solo performances climaxing with the hilarious complaint, “Even Hitler Had A Girlfriend,” before the band rejoins their determined leader for more dynamic merriment.

As he reflects back, Dr. Frank recounts, “I feel lucky to have survived. I may have done stuff that people think sucks, but never something that was fake. I’m proud of that.”