FOREWORD: Ted Leo is one of the most exciting performers in inide rock. His fast-fingered axe work, advanced literary sense, political defiance, and friendly demeanor make him way too multifaceted to be labeled a ‘punk.’ Born in South Bend, Indiana, he’d move to Jersey, then return to his native Indiana birthplace to attend prestigious Notre Dame University.

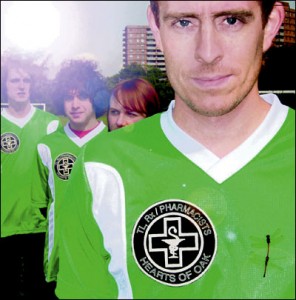

After playing in Chisel and other early bands, he went solo, then added the Pharmacists. A highly dependable and well-respected artist, I caught up with Leo during his ’03 tour for Hearts Of Oak, catching a Bowery Ballroom and Maxwells show along the trail. He has remained consistent, as ‘04s Shake The Sheets and ‘07s even better Living With The Living (highlighted by acerbic wartime rant, “Bomb.Repeat.Bomb”) attest. In ’09, his internet EP, Rapid Response, brought attention to Minnesota’s Republican National Convention police raids. This article was originally published by Aquarain Weekly.

Posing a dazzling triple threat as talented pop-rock song stylist, lyrically keen folk romantic, and fierce axe slinger, Bloomfield native Ted Leo is one of the Garden State’s most impressive musical entertainers. His father provided formative influences such as the Beatles, Buddy Holly, and Bob Marley, giving the pre-teen Leo a considerable understanding of genre differentiation that courses through his own eclectic compositional range. Though he never took guitar lessons, by age 19 Leo began raking the six-string with determined vengeance.

A Seton Hall High School graduate, he founded formidable punk band Chisel during sophomore year at Notre Dame with a DC-area student friend. After seven years and three albums together, they broke up and Leo, influenced by The Who, Small Faces, and The Jam, as well as hardcore punk, created short-lived mod revival three-piece, the Sin-Eaters, recording a demo and some live tracks while touring for a year.

Following a nifty ’98 self-titled solo debut on respected Jersey boutique label, Gern Blandsten, Leo hooked up with his first version of The Pharmacists for 2000’s more consistent Treble In Trouble EP. But it was the soon-to-follow full length, The Tyranny Of Distance, that brought the ever-changing unit national prominence.

Thereupon, Leo’s live shows became popular, impressing a legion of fans with nimble fretwork, scurried solo numbers, and delectable melodic interplay fronting a very capable bass-drum rhythm section. Three years after I first caught him at Chinatown club, the Bowery Ballroom, Leo sold out the same venue supporting ‘03s magnificent Hearts Of Oak and its thoughtful, stripped down 8-song companion, Tell Balgeary, Balgury Is Dead. Admirably, his increasing fan base showed up for this terrific Sunday night show despite a foot of snow curtailing highway travel.

Hearts Of Oak, in particular, reveals tremendous emotional anxiety and deep sociopolitical conviction juxtaposed by a dollop of heartwarming merriment. Yearning for ‘80s British ska pilots the Specials, Selecter, and Madness, the feverishly exhilarating “Where Have All The Rude Boys Gone?” finds Leo breathlessly huffing atop staggeringly dexterous licks Pete Townshend would be awed by. Raging with virile certitude, “The High Party” could bring fellow mod copper Paul Weller (whose “Ghosts” gets an acoustic spin on Tell Balgeary) to tears. And the reverent expressiveness of the scanty gauntlet “First To Finish, Last To Start” nips at the Impressions soul stirring righteous contemplation “People Get Ready.”

Hearts Of Oak, in particular, reveals tremendous emotional anxiety and deep sociopolitical conviction juxtaposed by a dollop of heartwarming merriment. Yearning for ‘80s British ska pilots the Specials, Selecter, and Madness, the feverishly exhilarating “Where Have All The Rude Boys Gone?” finds Leo breathlessly huffing atop staggeringly dexterous licks Pete Townshend would be awed by. Raging with virile certitude, “The High Party” could bring fellow mod copper Paul Weller (whose “Ghosts” gets an acoustic spin on Tell Balgeary) to tears. And the reverent expressiveness of the scanty gauntlet “First To Finish, Last To Start” nips at the Impressions soul stirring righteous contemplation “People Get Ready.”

As for Tell Balgeary, Leo mostly goes-it-alone on electric guitar-and-voice versions of his own material and worthy covers of Split Enz loopy “Six Months In A Leaky Boat” and Ewan McColl’s Celtic bourgeois Blues “Dirty Old Town.” His pedantic wit, observational antidotes, and punctual strumming invoke leftwing activist Billy Bragg sans the menacingly overt Socialist shrewdness.

Initially, your former band, Chisel, made DC its base. Then, you moved to Boston before coming back to hometown, Bloomfield, New Jersey. What’s up?

TED LEO: We were gonna move to Chicago after college. It’s an hour from South Bend. That’s where we had shows and some connections. But John, our drummer, got an Amnesty job, so since I wasn’t moving home, DC was fine. When Chisel broke up, I spent six more months in DC, but I was dating someone from Boston and got nostalgic for the Northeast. At that time in DC, everyone was tight and in serious bands. I felt I should make a break and start anew.

How’d your self-titled solo ’98 debut on Gern Blandsten set the tone for the future?

TED: People hated that record. There are 19 songs – 10 just solo with guitar. The others have tape-looped samples, dancehall and hip-hop beats. I listen to reggae more than anything and at that time there were new Lee Perry compilations. I got into that and had all these tapes I was messing around with and it all cohered into a thematic album. In retrospect, that served to contextualize the actual songs. But some people thought the songs took a backseat.

Were the sparer songs similar in scope to the solitude electric guitar-and-voice ramblings regaling Tell Balgeary?

Definitely. Some had faster Billy Bragg-like strumming. There’s also quieter stuff than I’ve done since – my attempts at soulful moments.

Tell Balgeary’s stripped-down version of “The High Party” got me believing the pointed lyrics were directed at the Bush administration.

(laughter) To be honest, the title came from the high guitar part. When the lyrics came along in that political vein, other thoughts of what the words may mean came in.

“A shitty war to fight for Babylon” seemingly nips at the Iraqi invasion.

I think (Secretary of State) Donald Rumsfeld is evil. He’s too slick.

You use Ewan Mac Coll’s “Dirty Old Town” as a forum for Bloomfield’s controversial Harvest Fest.

It’s awesome to celebrate the historic district of town I live in. But I see a new influx of commuter population wanting a tiki version of Williamsburg, Virginia, or a smaller Times Square. That pisses me off!

You save your most savage commentary for the visceral respite, “Loyal To My Sorrowful Country,” which scorns American oppression in a manner folk legends Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, or Phil Ochs could appreciate.

Maybe this is pompous, but the implication isn’t America sucks, but that it’s been co-opted, disenfranchising people. It’s a rallying cry with a glimmer of sadness. Folk music is a well I draw on for vibe, vocal melodies, or chord progressions. I thought I’d do something specific to that tradition. The song’s a challenge. I don’t plan to renounce my American-ness. I love where I’m from. When I sing it, I feel it to my core. But I could talk to you about struggles and temper that. Maybe it’s an exorcism to get the anger out so I can come back to the table and be more constructive.

Besides better songwriting and tighter arrangements, how would you contrast Hearts Of Oak to previous LP, Tyranny Of Distance?

Hearts Of Oak captured the band in one room playing together. With Tyranny, there was a loose feel – which actually worked. It was me, a singer-songwriter, inviting friends to the studio to play my songs, whereas Hearts Of Oak is more focused.

Compare Nicholas Vernhes’ Hearts production to Brendan Cantor of Fugazi’s work on Tyranny.

They’re both skilled and have known me for years. With Tyranny, the sonic template was like Paul Mc Cartney’s Ram – splashy ‘70s drums and glam-rock guitar. Brendan helped me get that. On Hearts, there was a tighter sonic structure Nick tried to capture.

The Irish-styled talk-sing violin-drum arrangement for Hearts opener, “Building Skyscrapers In The Basement,” navigates Celtic folk.

Putting that song upfront – it wouldn’t fit anywhere else – I hoped it’d set the tone. If “Rude Boys” were first, people might misunderstand the record as being a fun pop record. But it’s a lot more serious.

The guitar work on “Rude Boys” hearkens to Thin Lizzy.

Without a doubt, Thin Lizzy’s first guitarist, Eric Bell, was a super influence. He’d played in Them with Van Morrison during the ‘60s.

The full-on dramatic version of “The High Party,” with its descending ‘drink down the poison’ choral hook, reminded me of Elvis Costello due to the snarled tenor-screamed crescendo and murky organ drone.

People drop the Elvis comparison a lot. I like him just fine, but he’s not a conscious influence. However, there’s no question that has a lot of Elvis Costello in it.

“The Ballad Of Sin-Eater,” indelibly named after your old band, touches upon the ugly American theme while celebrating UK rail workers.

It’s not named after the old band. I’m just obsessed with the concept of sin-eaters, an Irish-Welch term. When someone dies, they placed a loaf of bread on their chest, hire a sin-eater to munch on the bread, thereby taking that persons’ sins as an untouchable bearer of sin doing the dirty work. There’s metaphorical modern parallels you could find right down to the grunts in the field who take the heat for bullshit political machinations of boardroom fat cats.

In Tell Balgeary’s publicity sheet, you mention how too little money and lack of exposure discourage fruitful artists enough for them to quit trying. Captain Beefheart gave up his valiant musical pursuit for sculpting and painting due to this dilemma.

There’s underlying motivations why you do it. Age is a factor. I’ll never stop playing and doing shows, but when does it stop becoming what I’m trying to do to make a living. In the past, it didn’t matter that I was slugging it out in the trenches just to do it for love. But now, I’ve had some success at 33, so taking risks that are easier at 23 is scarier. So I’m on the razor’s edge for the next few albums.

-John Fortunato