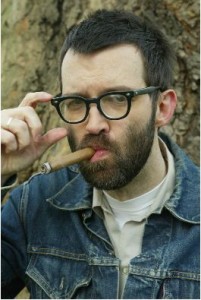

FOREWORD: Steve Earle may be the most loquacious musician I ever met. I’d interviewed him for Gallery Magazine during ’97s El Corazon hit the stores. We talked about football, politicians, and music for over 90 minutes. On ’02s Jerusalem, Earle made front page headlines for sympathizing with American-bred Muslim sympathizer, John Walker, a post-911 rightwing target. Earle offered no apology and went about his business. ‘04s hard-hitting The Revolution Starts Now and ‘07s Washington Square Serenade continued to snarl in the face of neo-conservative agenda. What’ll Earle come up with now that lefty Obama’s the prez.

This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly. It's followed by the original Gallery piece I entitled Bad Boy Balladeer Is All Heart On El Corazon.

FOREWORD: Steve Earle may be the most loquacious musician I ever met. I’d interviewed him for Gallery Magazine during ’97s El Corazon hit the stores. We talked about football, politicians, and music for over 90 minutes. On ’02s Jerusalem, Earle made front page headlines for sympathizing with American-bred Muslim sympathizer, John Walker, a post-911 rightwing target. Earle offered no apology and went about his business. ‘04s hard-hitting The Revolution Starts Now and ‘07s Washington Square Serenade continued to snarl in the face of neo-conservative agenda. What’ll Earle come up with now that lefty Obama’s the prez.

This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly. It's followed by the original Gallery piece I entitled Bad Boy Balladeer Is All Heart On El Corazon.

Perhaps the busiest Country & Western-based Nashville cat hitting the scene, bearded bard Steve Earle combines the folk ruminations and fingerpicking guitar style of disciple John Prine with Townes Van Zandt’s nostalgic emotional yearning and David Allan Coe’s rugged outlaw sensibility. His well-respected ’86 debut, Guitar Town, utilized meatier arrangements and a more prominent beat than neo-traditionalist contemporaries Dwight Yoakam and John Anderson, working pliable rock aggression into back porch hillbilly sensibility.

Originally from heartland Texas, this proudly leftwing, self-proclaimed ‘last of the hard-core troubadours’ was busted for heroin after ‘87s sleek Exit 0, ‘88s boogie shufflin’ Copperhead Road, and ‘90s darkly soul bearing road-as-metaphor The Hard Way failed to establish him as a recklessly authentic American icon.

Following a jail stint, the sober, revitalized Earle brought in roots-driven Norman Blake and Peter Rowan on mandolin and dobro to spice up ‘95s Train A Comin’ before ‘96s reconciliatory I Feel Alright faced romantic loss head-on.

By ‘97s confidently laid-back El Corazon, Earle’s unfettered, relaxed assuredness led to The Mountain, a monumental bluegrass set featuring the pristine Del Mc Croury Band.

While ‘00s Transcendental Blues invoked folk-blues legend Woody Guthrie as channeled through the Beatles Rubber Soul, the recent Jerusalem takes on timely concerns such as misguided fundamentalism (“John Walker’s Blues”), controversial maquiladoras (the Doug Sahm-inspired organ-riffed drug smuggler “What’s A Simple Man To Do”), and corporate betrayal (“Amerika V. 6.0,” with its rhythm guitar curling into the Stones’ “Jumping Jack Flash” before copping Buffalo Springfield’s “Mr. Soul”).

AW: Do you think the media gave you fair representation concerning the controversial “John Walker’s Blues”?

STEVE EARLE: People reacted the way I expected. Mainstream media reacted to them. Some of the lines came straight out of his mouth.

Why does Walker’s voice sound like Tom Waits in song?

Those taped t.v. snippets showed him exhausted, naked, duct taped to a board. He had a bad day. His voice dropped down low.

I agree he wasn’t a serious Taliban threat, merely a foot soldier.

He had no prior knowledge of the September 11th attacks. Neither did some hijackers. He left the country with no intention of returning. He was 14, got completely immersed in hip-hop, and looked outside his culture for something. He discovers the black cultural experience, goes to see Malcolm X, discovers Islam, and attends a Mosque in Marin. His parents told him he could study abroad and he decides to go to Yemen after graduating high school at 16. It’s a hotbed for fundamentalism. Afterwards, he finds out his parents separated, father came out of the closet, and his whole world turned upside down. Any fundamentalist is down on homosexuality so he goes back to Yemen.

I didn’t go off half-cocked and wrote a song. Next time his parents hear from him, he’s going somewhere cool for the summer. Which happens to be Afghanistan. He left there, went to Kashmir, and when we started attacking the Taliban, Islamic fighters from the region went to fight. People vilified him but he had no direct role in the attacks and deserved to be treated like a human while being judged. He was being treated as the poster child for our fears. It’s ugly scapegoating. It turned into racism and discrimination, the opposite of what this country’s about.

Is it difficult to compose political songs since instrumentation is spare to stress your vocals?

I think that may be why the record is spare, but it wasn’t conscious. The record was idea-driven. Transcendental Blues was me becoming fascinated with melody and textures. I spent time with overdubs, listened to Beatles records, and turned shit around backwards. This record was more like, bring in three songs and cut a track until we got one that smoked. I listened back, put a tambourine on, and mixed the fucker. It was a real immediate experience. I was concerned the lyrics should be understandable to tell the story best.

“Amerika V. 6.0” addresses HMO’s.

We’re in a de-regulating society letting the market handle everything. The reason that’s not feasible is people go without medical treatment and go hungry. The market isn’t designed to take care of everyone. As a fundamental idea, Capitalism is oppressive because it requires a surplus of labor to thrive. I have nothing against free enterprise, but we’ve been dismantling legislation starting with the New Deal, allowing regulation for humans. Left to their own devices to do the right thing, they’re simply not highly evolved enough.

I was serving one-year probation and parole after jail. I had to pee for police once a week. But I wanted to not be a heroin addict so badly I welcomed it. I couldn’t have stayed clean if I didn’t have to show up with clean piss. I would’ve cheated. You can’t let politicians in Southern states control health care because they’ll steal the money. Rules keep us from hurting ourselves with corruption. I live in Ground Zero for HMO business, Nashville. That shouldn’t be privatized and left to the highest or lowest bidder.

Does “Conspiracy Theory” deal with repressing the belief 9-11 actually happened?

For 45 minutes, we were all on the same wavelength focusing on the people’s family’s horror. Then, we thought how it was gonna affect me. I was thinking about the death penalty and how we were all in an ugly retributive mood. I wanted to know where my son was since he registered for the draft. There are people who had an agenda to go after Iraq. The danger is it perpetuates the lie of why we’re going into Iraq. Saddam poses more of a threat to his neighbors, but we’re thinking of going in unilaterally. That’s isolating us from the world. When you start talking about al-Qeada and Saddam being the same thing, that’s racism. From that point, we’re fighting a war against a belief system and a race of people. Our government will tell you they hate us because we’re free. Bull shit. They hate us because we support Israel and its oppressive regime. We weren’t concerned with the foreign entity occupying Afghanistan passing out burkas until 9-11.

You close the album with the “Jerusalem.”

I was amazed how ignorant I was of Islam. I didn’t know devout Muslims say ‘peace be upon him’ every time they say Jesus. He was the last prophet before Mohammed. They worship the same God as Christians and Jews. It’s the God of Abraham. This country doesn’t operate well without a boogie man. Since the Soviet Union fell and Khadafi keeps his head down, the Palestinians are the new enemy. My spiritual belief may be retarded since I’m not really Christian, but I believe there is a God. We’re coming back to Jerusalem for 2,500 years because we’re supposed to get it right. If we get that right, all else will be easy.

What records have you bought recently?

Springsteen’s

The Rising and

The Eminem Show. Dre is real good at producing (Eminem). I was scruffing for hits on the street, didn’t even have a guitar, when Dre’s

The Chronic came out. So I figured I’d head over to the shop where they sell hip-hop and drug paraphernalia on Charlotte Avenue in Nashville and I’d buy myself two pipes, some screens, and ten cassettes of

The Chronic. And if I ran out of money in the middle of the night, I could always trade a copy for some dope.

STEVE EARLE

STEVE EARLE

While growing up in Texas, esteemed singer-songwriter Steve Earle listened to Country, rockabilly, and Blues, musical styles that’d inform his six marvelous studio albums to date. Gaining exposure and critical attention with his ’86 debut,

Guitar Town, Earle secured his status as an accomplished composer admired by his peers.

But while Earle’s rootsy music was shunned by compromised contemporary Country/ Western radio, Garth Brooks and Randy Travis welcomed him with open arms shortly thereafter.

Following the libertine sophomore effort,

Exit 0, and the rockin’ powerhouse,

Copperhead Road (which remarkably consolidated his edgy rural tales of disobedience and paranoia), Earle spent some time in jail for heroin abuse. Upon his release, he cut ‘91s somber retreat,

The Hard Way, emotionally detailing seclusion, solitude, and regret. Its brilliant follow-up,

I Feel Alright, caught the Nashville-based troubadour celebrating life while absolving guilt-ridden feelings with uncanny frankness.

On his latest,

El Corazon, Earle again relates small town observations with a keen eye. And he does so with an incredible assemblage of talent. Emmylou Harris adds close harmonies to the stormy "Taneytown;" the Supersuckers (who just released a five-song EP with Earle) help tear up "N.Y.C;" bluegrass traditionalists the Mc Coury Brothers keep the home fire burning on the folksy "I Still Carry You Around;" and the Fairfield Four sizzle through "Telephone Road."

As for the near future, Earle plans to tour with hillbilly legend, Buddy Miller, and record a bluegrass album with the Del Mc Coury Band.

I spoke at length with the master craftsman via phone one sunny afternoon, October 1997.

When did you start playing guitar?

I had an acoustic guitar as a kid because my father didn’t want an electric guitar that would be too loud and get him upset. With all the kids in our house already, it was loud enough. I could never get my guitar to sound like Jimi Hendrix, but I could make it sound like folk artists’ Tim Hardin, Tim Buckley, and Bob Dylan. I started gravitating to coffeehouses, but I was too young to play those places.

Did local Texas radio and live shows inspire you to pursue music?

I listened to San Antonio’s KDSA, a local AM rock station that played the Beatles and Creedence. Texas was a great place to be from. There’s lots of live music. I had people in my family who played music, though only one professionally. My uncle turned me on to Jimmy Rodgers, a major influence on my music, and Bob Willis. Country radio was different in Texas than it was in the rest of America. It was dance music derived from Swing.

How is El Corazon different from previous albums?

How is El Corazon different from previous albums?

This record ended up all over the place. I’m the songwriter, but I let the songs dictate what musical setting I put them in. Luckily, I found a way of recording that glues the songs together.

Was it difficult to assemble such a great cast of players?

I originally tried to write a real straightahead two guitar/bass/drum record. But the songs dictated who I called to get in the studio. The record was bigger than me.

You sing in a nasal twang reminiscent of your good buddy, John Prine, on the politically stern "Christmas In Washington."

It’s not an accident that I sound like Prine since my picking style also comes from him. That song was written after the election night returns. Bill Clinton was bending over and kissing a load of asses and sold out whatever credibility the Democratic Party still had left.

Was it fun getting your son, Justin, to play guitar on the all out rocker, "Here I Am"?

It was the last song recorded for the album. I wanted to do a track with Brad Jones on bass and Ross Rice on drums. We just got the song running when Justin walked in from school. I told him, ‘get that green guitar over there.’ He plugged in and turned it loose. He listens to hip-hop and turned me on to Beck, who I have to agree with everybody, had the best album that came out in 1996. Beck’s a real musical cat.

"Fort Worth Blues" was written after your friend, singer-writer Townes Van Zandt, died. How close were you with Townes?

My son is named after him – Justin Townes. He gave me my apprenticeship along with Guy Clark. He’s the reason I’m here.

How’d you get involved with the Supersuckers?

They were always heavily interested in Country music. I applaud them for their temporary change of direction. I met them at Farm Aid after Willie Nelson asked them to play in Louisville. It was my first Farm Aid after jail. We became friends, ran into each other on the road, and talked about doing a split single. And I decided "N.Y.C." was perfect for them.

Did your heroin bust actually revitalize your career?

Sure it did. I never made a record I’m ashamed of. But

The Hard Way is a very spooky, dark record. And I didn’t release anything for awhile after that because I didn’t have an album left in me. If I hadn’t got arrested, I’d be dead by now.

But did you deserve to go to jail for being a drug user and not a drug dealer?

I wouldn’t have gone to jail if I’d shown up for the sentencing hearing. I’d have got probation. I don’t believe in the War On Drugs. It’s ludicrous because they never arrest the right people. While the government wages a war on drugs, they’re the leading culprit of bringing cocaine into the country. The US government was actively involved in trafficking drugs.

You’ve said if you had enough time you’d like to live in New York City. Why?

(Editors note: By 2008, Earle had moved to NYC with his current wife, singer-songwriter Alison Moorer)

I have to be careful in New York. I have a tendency to act badly there. They had the cheapest, strongest dope around. I always wanted to do a solo show somewhere other than the Bottom Line. Nothing against the owner, Art Pepper, but I always wanted to do Folk City and some of the older West Village clubs. I like Tramps, it rocks, as did the old Ritz and the Cat Club. A friend of mine turned me on to Joseph Mitchell, a North Carolina native who wrote for

The New Yorker. He did a collection of non-fiction articles called The Bottom Of The Harbor. It’s about the New York waterfront. He’d hang out at the Oyster Bar and the Fulton Market until someone must have had it in for him and they both got burned down.

Why is there so much animosity between Nashville and Memphis?

As far as I’m concerned, Memphis is the capital of Mississippi. (laughter) I’m pissed off at that Republican cocksucker governor of Tennessee and the Oilers owner, Bud Adams (a football owner caught in the war between the two cities). Copperhead Road was mixed in Memphis and I worked at Ardent Studios. But Memphis is a declining city that tries to make fun of Nashville.

That answer was as brutally honest as most of your songs. What gives you the conviction to write such personal songs?

The emotionally driven songs get better and therefore there are more of them. Those songs are my forte. But I’m also proud of "My Old Friend The Blues," "Valentines Day," and "Goodbye." "Goodbye" is currently my favorite song I’ve written. I let my guard down a lot more now. But there’s obviously some detachment when I write about a Confederate soldier killed in 1861. I’ve tried writing poetry, but I can only do prose. Poetry’s the purest, toughest form of art.

You have a collection of short stories due out soon.

I write something everyday. I often write prose because there’s not a melody hanging around. I’ve got an editor and when there’s a coherent collection I’ll make a book.

And you’re producing Clemson, South Carolina’s up and coming band, 6 String Drag.

Their High Hat record is coming out now. They remind me of The Band because they approach music from a musicologist standpoint. They turned me on to older music I never heard before. They also like the Stanley Brothers and Emitt Miller.

Do you think deserved neo-traditionalists such as Robbie Fulks, Wayne ‘The Train’ Hancock, and Paul Burch will ever get a fair shake at Country radio?

Not if radio is set up the way it is now. Wayne Hancock should certainly be played on Country radio. And Robbie Fulks is a great singer. But he does a lot of different styles of music. He could make a pop record as easily as a Country record. The first time I saw him he floored me. When I walked in the club halfway through the set, he did Townes Van Zandt’s "Fraulien" and it absolutely killed.

FOREWORD: After a nifty set at Maxwells in Hoboken, I told Fiery Furnaces multi-instrumentalist Matthew Friedberger that one of his epic numbers sounded like early Genesis. He didn’t appear pleased, but his sister, Eleanor, got a chuckle. Anyway, that was a few months after I did this interview with Matt in support of ‘04s audaciously unconventional full-length saga, Blueberry Boat. The brother-sister duo took an even bigger chance when they put their grandmother’s narrated stories to music on ’05s middling Rehearsing My Choir. Luckily, ‘06s brilliantly textural synth-pop masterwork, Bitter Tea, reached a high water mark, bettering ‘07s less dependable Widow City.

Valiantly trading elemental Epicurean efficacy for engagingly protracted eccentricities, the Fiery Furnaces (with bassist-keyboardist Toshi Yano and drummer Andy Kittles in tow) subsequently felt compelled to challenge conceptual limitations. Affectionately imitating the "Kit Lambert-influenced Who" of mini rock operas "Rael" and "A Quick One While He’s Away," the more abstract Blueberry Boat takes listeners through a pastoral pastiche of adventurous prog-rock escapades chock full of contrapuntal medleys, nautical sea shanties, carefree cabaret, ruffled ragtime, and scurried skiffle. The percussive opening mantra, "Quay Cur," ambitiously shuffles obsessive twists and oblique retreats, pitting the piano-laden neo-Classical grandeur of theatrical ‘70s visionaries Renaissance against early Genesis’ allegorical parables. The wondrous title track patches charmingly obtuse Zappa-esque befuddlement into bleating electronic hullabaloo while the sumptuously schizoid "I Lost My Dog" counters fast, busy snipes with slow, spare stanzas. On the exhilarating roundabout "Chris Michaels," Matthew’s guitar arpeggios recall idiosyncratic mentor Pete Townshend. Only the compact "Straight Street," with its luxuriant bluesy slide, reaches back to the radiant concision of Gallowsbird’s Bark.

Your arrangements seem affected by spectral ‘70s prog-rock bands such as King Crimson and early Genesis.

MATTHEW: I liked Peter Gabriel and Genesis, but I never had any of those records. I liked Eno as a teenager. I had his first four records and the pre-elevator music productions for Roxy Music. Roxy’s first two albums sound a lot like Eno’s Here Come the Warm Jets. But I was never a Yes fan. I liked King Crimson. They were cooler.

Were you aware of jazzier prog band, the Soft Machine?

I knew of them because they played on Syd Barrett’s solo debut, The Madcap Laughs. But I wasn’t a fan. I only had their Lark’s Tongue In Aspic record. When I was younger, I was afraid to like things that were too prog because in my immature mind I thought it went against anything cool like punk. When I was 14, you could like the Plastic Ono Band record because the Sex Pistols’ Johnny Lydon enjoyed it. But I was definitely a Who fan. The first tape I bought was Van Halen I, then Who’s Next. My favorite Who records are Quadrophenia and The Who Sell Out.

"Bow Wow," with its pristine piano hooks, snaky bass, and symphonic synth, truly reminded me of Christine Perfect before she joined Fleetwood Mac. Were their pre-Buckingham-Nicks records an influence?

No. I was prejudice against Fleetwood Mac before they came to L.A. We’re trying to build off late ‘60s light psychedelic pop but with Blues stuff added.

I couldn’t get to the bottom of the rhythmically abstruse "Asthma Attack."

That’s from an overheard conversation Eleanor picked up at work. They were talking about being in the Bahamas for vacation and someone had a story about how they cleared the beach because a shark was swimming in shallow water. Her co-worker said ‘I almost had an asthma attack.’ So it’s a silly lyrical quote translated onto a hectic beat.

Amazingly, Blueberry Boat’s lengthy opuses defy self-indulgence. You take some imaginative chances composing four 8-minute-plus tracks on it.

We had the opportunity to do more overdubs and thought it’d be just as risky making a record that sounded like the debut. Two-thirds of it was written before the first record came out. We hoped the two records would make more of an impression with the differentiation. They function as a demonstration of what we could do from simpler to not-so-annoying story songs. The funniest criticism of the debut was someone saying we should go to clown college because it sounded too much like a carnival.

Take me through the twixt text of "Blueberry Boat."

That song is about Eleanor driving a Sunfish up to a party boat on Lake Michigan and stealing beer from a cooler. Then, it flashes forward to her being captain of a container ship bringing a cargo of American produce, especially blueberries, in from Hong Kong. They get attacked by pirates in the South China Sea so she scuttles the ship and won’t give up the blueberries and goes down with the ship.

Were you into the early ‘90s Chi-town alt-rock explosion, which incorporated North Side stalwarts Liz Phair, Urge Overkill, and Shrimp Boat?

I was into Jesus Lizard more because they’re harder rockin’ and singer David Yow is hilarious live.

What current bands float your boat?

Electrolane, who I saw in Europe. We toured with Franz Ferdinand. I think they’re brilliant. Their singer has a lower voice so he doesn’t sound like an Ian Curtis imitation and he doesn’t yelp like Duran Duran. Stylistically, it’s familiar, but they mix rock and pop elements well.

How will your next album differ from its predecessors?

We’re gonna do a record in Chicago with my grandmother, who’s gonna sing ballad duets with ‘50s rock and roll influences. We love Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley so we want to do our imitation of our idealized Chess records version. It’ll be about expectations going wrong, a time travel with Eleanor singing the young persons’ parts and my grandmother filling in the aging role.

Valiantly trading elemental Epicurean efficacy for engagingly protracted eccentricities, the Fiery Furnaces (with bassist-keyboardist Toshi Yano and drummer Andy Kittles in tow) subsequently felt compelled to challenge conceptual limitations. Affectionately imitating the "Kit Lambert-influenced Who" of mini rock operas "Rael" and "A Quick One While He’s Away," the more abstract Blueberry Boat takes listeners through a pastoral pastiche of adventurous prog-rock escapades chock full of contrapuntal medleys, nautical sea shanties, carefree cabaret, ruffled ragtime, and scurried skiffle. The percussive opening mantra, "Quay Cur," ambitiously shuffles obsessive twists and oblique retreats, pitting the piano-laden neo-Classical grandeur of theatrical ‘70s visionaries Renaissance against early Genesis’ allegorical parables. The wondrous title track patches charmingly obtuse Zappa-esque befuddlement into bleating electronic hullabaloo while the sumptuously schizoid "I Lost My Dog" counters fast, busy snipes with slow, spare stanzas. On the exhilarating roundabout "Chris Michaels," Matthew’s guitar arpeggios recall idiosyncratic mentor Pete Townshend. Only the compact "Straight Street," with its luxuriant bluesy slide, reaches back to the radiant concision of Gallowsbird’s Bark.

Your arrangements seem affected by spectral ‘70s prog-rock bands such as King Crimson and early Genesis.

MATTHEW: I liked Peter Gabriel and Genesis, but I never had any of those records. I liked Eno as a teenager. I had his first four records and the pre-elevator music productions for Roxy Music. Roxy’s first two albums sound a lot like Eno’s Here Come the Warm Jets. But I was never a Yes fan. I liked King Crimson. They were cooler.

Were you aware of jazzier prog band, the Soft Machine?

I knew of them because they played on Syd Barrett’s solo debut, The Madcap Laughs. But I wasn’t a fan. I only had their Lark’s Tongue In Aspic record. When I was younger, I was afraid to like things that were too prog because in my immature mind I thought it went against anything cool like punk. When I was 14, you could like the Plastic Ono Band record because the Sex Pistols’ Johnny Lydon enjoyed it. But I was definitely a Who fan. The first tape I bought was Van Halen I, then Who’s Next. My favorite Who records are Quadrophenia and The Who Sell Out.

"Bow Wow," with its pristine piano hooks, snaky bass, and symphonic synth, truly reminded me of Christine Perfect before she joined Fleetwood Mac. Were their pre-Buckingham-Nicks records an influence?

No. I was prejudice against Fleetwood Mac before they came to L.A. We’re trying to build off late ‘60s light psychedelic pop but with Blues stuff added.

I couldn’t get to the bottom of the rhythmically abstruse "Asthma Attack."

That’s from an overheard conversation Eleanor picked up at work. They were talking about being in the Bahamas for vacation and someone had a story about how they cleared the beach because a shark was swimming in shallow water. Her co-worker said ‘I almost had an asthma attack.’ So it’s a silly lyrical quote translated onto a hectic beat.

Amazingly, Blueberry Boat’s lengthy opuses defy self-indulgence. You take some imaginative chances composing four 8-minute-plus tracks on it.

We had the opportunity to do more overdubs and thought it’d be just as risky making a record that sounded like the debut. Two-thirds of it was written before the first record came out. We hoped the two records would make more of an impression with the differentiation. They function as a demonstration of what we could do from simpler to not-so-annoying story songs. The funniest criticism of the debut was someone saying we should go to clown college because it sounded too much like a carnival.

Take me through the twixt text of "Blueberry Boat."

That song is about Eleanor driving a Sunfish up to a party boat on Lake Michigan and stealing beer from a cooler. Then, it flashes forward to her being captain of a container ship bringing a cargo of American produce, especially blueberries, in from Hong Kong. They get attacked by pirates in the South China Sea so she scuttles the ship and won’t give up the blueberries and goes down with the ship.

Were you into the early ‘90s Chi-town alt-rock explosion, which incorporated North Side stalwarts Liz Phair, Urge Overkill, and Shrimp Boat?

I was into Jesus Lizard more because they’re harder rockin’ and singer David Yow is hilarious live.

What current bands float your boat?

Electrolane, who I saw in Europe. We toured with Franz Ferdinand. I think they’re brilliant. Their singer has a lower voice so he doesn’t sound like an Ian Curtis imitation and he doesn’t yelp like Duran Duran. Stylistically, it’s familiar, but they mix rock and pop elements well.

How will your next album differ from its predecessors?

We’re gonna do a record in Chicago with my grandmother, who’s gonna sing ballad duets with ‘50s rock and roll influences. We love Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley so we want to do our imitation of our idealized Chess records version. It’ll be about expectations going wrong, a time travel with Eleanor singing the young persons’ parts and my grandmother filling in the aging role.