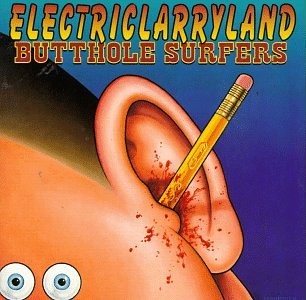

FOREWORD: Wacky Texas boho mofos, the Butthole Surfers, concoct a toxically chronic stew from radically skewed psychedelia-encrusted noise-seared punk rock and haywire electronic gadgetry. After more than a decade in the murky underground, they got their one post-grunge commercial radio break when dusky slacker anthem, “Pepper,” caught everybody’s attention and got people in the stores to buy their seventh studio LP, ‘96s Electriclarryland.

FOREWORD: Wacky Texas boho mofos, the Butthole Surfers, concoct a toxically chronic stew from radically skewed psychedelia-encrusted noise-seared punk rock and haywire electronic gadgetry. After more than a decade in the murky underground, they got their one post-grunge commercial radio break when dusky slacker anthem, “Pepper,” caught everybody’s attention and got people in the stores to buy their seventh studio LP, ‘96s Electriclarryland.

I got to see the Buttholes at Roseland Ballroom in ’96 with my friend, Frank, consuming rum and cokes with the band long after their resounding loud-as-fuck hour-and-a-half set. The next day, those anuses at Capitol Records (not including Bobbie Gale) scheduled an 11 AM interview. Guitarist Paul Leary, nursing a hangover, was pissed at those dumb-asses. And the Capitol rep tried to keep me from discussing singer-keyboardist Gibby Hayne’s heroin problems even though it was Gibby that began taking the conversation that way. Anyway, much herb was cooked and we all had a fuckin’ blast.

Since ’01, Butthole Surfers have remained dormant. Gibby got married and lives in Brooklyn. Paul had already become an in-demand producer working boards for Sublime, Meat Puppets, Daniel Johnston, and Reverend Horton Heat in their prime. Drummer King Coffey did well with his boutique label, Trance Syndicate, releasing discs by pre-fame And They Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead and ex-13th Floor Elevator psych-garage schizo, Roky Erickson (amongst others).

The following piece is comprised of that late morning conversation and appeared in Brutarian (a great DC mag with superb underground articles and even better illustrative drawings started in the ‘90s by Dominick Salemi). Afterwards, I’ve added a Paul Leary interview from ’01 promoting Weird Revolution that originally ran in Aquarian Weekly.

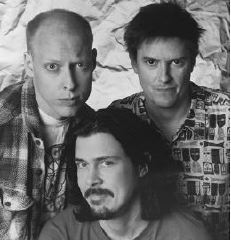

Ladies and gentlemen, the Butthole Surfers: singer Gibby Haynes, a six-foot-six longhaired gutter rat who’s not nearly as stark, grim, or demonic as painted by the mainstream press; guitarist Paul Leary, who, truth be told, is much more frightening than the aforementioned, ready to unleash his ornery angst at any given moment when not letting loose with frank observations and candid retrospection; and King Coffey, a drummer anchoring not only these Buttholes, but his own record label, Trance Syndicate.

Recording since ’81, the Buttholes know the rock and roll game well and now stare national stardom in the face thanks to the burgeoning popularity of ‘96s maladjusted pop-slopped sleaze, Electriclarryland.

Since I’ve followed Texas music for quite awhile, I’d like to know if the Butthole Surfers have ever met respected underground legends, 13th Floor Elevators?

HAYNES: Yeah. Roky was a great guy. We put a record out on his label.

COFFEY: You could make an argument that if you look at Texas popular music, there’s a weird element running through it. Some of the musicians from the ‘50s, like Roy Orbison, certainly looked weird. Buddy Holly kinda sounded weird when he came out with his heavy drum roll and the toms. He was one of the most original white musicians. You could look at the ‘60s with ? and the Mysterians and “96 Tears.” Then even the Texas psychedelic scene was weird by psychedelic standards. In the ‘70s there was ZZ Top, one of the strangest bands on the planet. They have a successful repertoire that could be considered mainstream.

HAYNES: Well, Willie Nelson just totally fucked off everybody. He totally did his own thing differently. I mean, there’s just something about Tex artists.

COFFEY: Like Mr. Haynes just pointed out, Willie Nelson, is considered a Country singer, but really he’s a Jazz singer. He may do Country, but he’s a Jazz player. Willie could do what he wants. And he’s never had a successor.

LEARY: (just walking in the door half asleep) Goddamn…

COFFEY: There’s Paul Leary.

LEARY: Who fucking scheduled this shit so early? Is this Capitol Records idea of a goddamn joke? I just think this is retarded. (calming down) Oooh, I had such a good dream going. I was dreaming I was sleeping.

HAYNES: Within the last year, I actually had a wet dream. I actually woke up with the semen all over my tummy. I even called Bill Carter and told him. (laughter)

Have your songs become more reflective as you’ve grown up? Like “Pepper” deals with several interesting characters.

Have your songs become more reflective as you’ve grown up? Like “Pepper” deals with several interesting characters.

HAYNES: (laughing) Oh, I thought you were gonna say it sounded like Beck because I use the word ‘like’ in it.

Do you guys think of yourselves as unpretentious vulgar bohemians who’ve never been involved or related to any one scene?

HAYNES: I think it’s just the name of the band. I can’t think of a truly vulgar song. The name is a sophomoric junior high joke. And I think people just assume we’re stupid, goofy, immature males – which we are – but there’s humor in there. It’s generally not a punchline, one liners. We hardly ever have any foul language on our records.

Do you feel more comfortable with your songs than you did back in ’83?

LEARY: I think the best pop riff we ever wrote was on our ’81 song, “Hey.” Everyone of our albums has one justifiable pop song on it. We’re a pop band.

And a very unconventional one at that. Who came up with the theme for the “Pepper” video with Erik Estrada?

COFFEY: Video directors come up with videos.

You had nothing to do with the story line?

HAYNES: No. Record companies won’t have anything to do with artists directing – unless you’re some huge star. It’s a lot more involved than it looks. But I would include “Pepper” as being another shitty video. It’s as good as 90% of the stuff on MTV, but it’s disappointing not to get a real good video done.

COFFEY: I specifically asked to have Michael and Janet Jackson in our video going through space watching us perform. But Capitol turned it down.

So why bother doing a video then? Did you guys get too big and Capitol needed some more promotional material?

LEARY: Well, it was a top tune on the MTV playlist. That’s why you do it. It translates into sales. Plus, it’s fun to make.

HAYNES: You know what I like? If you’re a big band you can smoke and drink booze in your videos. If we had two or three platinum records on the walls, we could be slamming dope in our videos.

Do you guys ever go onstage fucked up before sets and wonder what the hell you’re doing up there?

HAYNES: All the time. Just kidding. No one can go onstage and play better if they’re all doped up. If I smoke pot before I go on, I get real paranoid about how the kids are getting ripped off. It just freaks me out.

LEARY: If music is not real, then pot is not a drug. If we were to take cocaine, then you couldn’t play an instrument if you hadn’t before. But with pot, you could believe the lie that you could play. And it makes it much more enjoyable. Driving is a little easier when you’re stoned, but heroin and cocaine are not driving drugs. I’m much safer in my car when I’m stoned.

How could you describe the Buttholes’ sound to a musically unhip person?

LEARY: We’re a pop band. Listen to our first motherfucking album. We rhyme ‘love’ with ‘dove.’

COFFEY: Just listen to the very first song on the very first album. We’re a pop band as we’ve already noted.

LEARY: It’s only recently that we’ve been doing bullshit rock music because of what people demand.

Why do you differentiate between pop and rock music?

COFFEY: Ah, let’s not. They’re both the same. Now bullshit rock, that’s different…

LEARY: Grand Funk Railroad was a pop band. Still, it doesn’t rock harder than that.

Is it true Walmart decided not to carry Electriclarryland because of the cover having a picture of a cartoon character with a pencil shoved in his ear?

COFFEY: No. They’re carrying it now. You never know. Best Buy had a campaign a couple years ago where there was a son talking to his mom about bands he likes, and one of the bands he mentioned was the Butthole Surfers. No one thought twice.

Who are some guitar influences, Paul?

LEARY: Mark Farner of Grank Funk, Roy Clark, Gene Simmons… I don’t care what kind of music they play, as long as they’re good.

On the other hand, the media has made you guys much bigger monsters than you come off as. Do you think the image is justified? Do you think the fans see it this way?

LEARY: The Butthole Surfers don’t really have an image. Like you look at the band Psychotica with the guy with no penis who comes out in a silver suit and they have colored smoke – that’s an image. ZZ Top has an image. We are without image. We are all surface area with no volume.

COFFEY: And so therefore, people have not distorted our image enough.

So it’s time to distort your image more?

COFFEY: It’s up to you to distort our image.

HAYNES: If we can be said to have an image, it’s a creation of the press.

Well, I think with some of the things you do, you push the envelope a little bit. You’re anti-image so you sort of create an image.

HAYNES: It’s really difficult to not have an image.

COFFEY: Hey, remember that guy who had that really shitty pickup truck in Austin? And on the back window on the top written in dust was “Dino De La Hoya”?

LEARY: I saw a Plymouth with custom lettering. The guy spelled Plymouth ‘P-l-i-m-o-t-h.’ It was all crooked. But pachucos, to me, are the most influential artists in the world. A pachuco will take anything and turn it into something great to reflect his own unique and individual style. It’s usually a reflection of him sniffing the glue. If you’ve never hung out with some guys sniffing a red rag… that’s so fucking cool.

HAYNES: Like a guy who wears his jockstrap on the outside of his pants. Now that’s art.

Low Rider magazine would appreciate this. They had an issue devoted solely to airbrush art.

LEARY: That’s a smokescreen because the true art is the bitter art within. Have you ever heard a pachuco say ‘Hey hippie, suck my peepee?’ I bet they didn’t put that in Low Rider. They weed out the guys who call themselves artists and flush them down the commode. I’m from San Antonio and I worship pachucos. My goal in life is to be a pachuco. But I was really bummed out when I couldn’t be a pachuco. I had all that Irish heritage I had to deal with.

HAYNES: As a band one time we tried to become pachucos. We had these khaki pants that were about twenty inches too big in the waist, and extra extra large flannel shirts and white undershirts and hairnets. King looked good in a hairnet.

LEARY: We went and bought those pointy shoes that were called Delega-tays.

COFFEY: They were fake Stacey Adams.

LEARY: Yeah. We couldn’t afford the real ones.

COFFEY: Actually, they were called Delegates. We preferred to call them Delega-tays.

HAYNES: Little roach killers.

You have a problem with roaches?

LEARY: Gibby nailed two of his cockroaches to the wall of his tool shed in San Antonio where we recorded our first record. And they appeared to die from time to time. But a few minutes later you’d hold a lighter to it and it’s dance.

HAYNES: I had a pet roach one time and all he ate was one bean and a human hair. Then he finally died. You could tell he was eating the bean because just a little bit of it would be gone.

How do you guys feel about being made poster children for the Christian Coalition?

COFFEY: I think it’s cool how the Christian Coalition is the key to the Republican party now. I think that’s rocking. They couldn’t win without them so Dole had to pick someone who was anti-abortion.

So I doubt you’ll be voting for the Republican ticket in the near future.

COFFEY: You’ll never catch me in a voting booth. The only booth you’ll catch me in is the one you got to put quarters in.

Well, I voted for myself. I think Clinton’s a dick and a liar.

LEARY: I think his wife is a bigger dick and a liar.

HAYNES: I like Hillary Clinton because she refuses to be made fun of. She’s the sexiest thing in the White House since Jackie O.

LEARY: No. I disagree. The sexiest thing in the White House is Chelsea. She’s got so hot lately. She’s really come into her own.

Wouldn’t you like to find out she’s a Butthole fan?

LEARY: I’m sure she likes “Pepper.” I did meet Amy Carter. And she was wearing a Psychedelic Furs t-shirt.

COFFEY: She, on the other hand, is more intellectually attractive.

And Chelsea inspires thoughts of debauchery! If she had invited you would you have played at one of the inaugural balls?

HAYNES: I think it’s sick when bands do that. If I ever see Michael Stipe I’m gonna give him shit. Natalie Merchant and Michael Stipe up there singing for the President of the United States!

COFFEY: We had a bass player years back who lost all respect for the Turtles when they played at Trisha Nixon’s party.

Playing at a birthday party, even Trisha Nixon’s is different from playing an inaugural party.

HAYNES: Nixon was a good president.

COFFEY: Yeah, but he had a potty mouth.

HAYNES: LBJ had a potty mouth.

LEARY: He used to bark his orders to his aides from the toilet. I used to work for a guy like that at a lumber yard.

COFFEY: LBJ was the coolest because if he ever had a problem with anybody, he had one simple solution. He’d take off his clothes and his problems would go away. All his detractors would disappear.

Didn’t you guys go onstage naked once? Was that a political statement?

HAYNES: No. It was because I forgot to wear underwear. Otherwise, I would have been underwear clad.

LEARY: Take off your clothes and go stagediving until you realize there’s a finger up your butt. You can get your dick snapped. You ever been dick snapped?

Not that I can remember. And speaking of snapping, what about the Turtles? You’ve covered stuff before, ever had any desire to do a Turtles song?

COFFEY: No, because the Turtles are pricks. The whole De La Soul thing with the samples was bullshit. They wrote some great songs. But I’m not going to contribute any money to them because they’re fucking assholes. Plus, they were doing that Six Flags amusement park tour thing. I met some people who went to that and they said the Turtles really sucked hard.

So in the twilight of your career you couldn’t see yourself playing a park like New Jersey’s Great Advernture?

COFFEY: I’m really looking forward to the Holiday Inn days. That’s the ultimate gig. Maybe those Vegas clubs. We’d just play loud as shit in the lounge.

LEARY: What about that Gospel group who was making too much noise in that one hotel we were at? Those fucking assholes wouldn’t shut up, singing gracefully to the Lord. I told them joyfully to shut the fuck up.

Still, our readers want to know: are there any songs you’d pick as covers?

HAYNES: Soft Cell.

LEARY: I want to do Glen Campbell’s “Dreams Of The Everyday Housewife.”

You should do “Wichita Lineman.”

HAYNES: Jimmy Webb is a pretty cool writer. (The band breaks into a hip-hop version) Jimmy Webb was an acid shaman genius. Anyone who wrote both “Wichita Lineman” and “Up Up And Away” is just… I just discovered Jimmy Webb. I’m not that musically literate. But I know the real deal when I see it.

Which one of you saw John Mc Laughlin at his first live gig?

HAYNES: That was me. Dr. John, Mc Laughlin, and the Allman Brothers. The show started at 11:30 in the morning and was over at 3:30 in the morning in Dallas. My dad was waiting in the car from midnight until 3:30. Didn’t get mad, just asked how I enjoyed the show.

LEARY: The police escorted me out of my first two shows. Grand Funk Railroad and Creedence Clearwater Revival. We got to shoot the finger at the pigs. We had my dad drop us off behind the arena so we could jump the fence and get in.

COFFEY: My most influential early show was the Ohio Players’ “Love Rollercoaster” tour featuring K.C. & The Sunshine Band and Hot Chocolate. And my dad and I were the only people there wearing blue jeans and sandals. It was really amazing…

I assume you guys are making money now. How are you using it to better your lives?

LEARY: That’s rich. We’re on MTV. You get a hit on the radio and everyone thinks the mailman just starts bringing in the fucking checks. I love that.

COFFEY: Well, I like people who are confused. They see Erik Estrada on TV in the video and they’re like, ‘Wow, they’re making money.’

Do you make money touring?

LEARY: That’s another great myth.

COFFEY: Horrible year for tours.

LEARY: I haven’t seen a check for any of this shit.

COFFEY: We would have made money if we didn’t take out any lights or any musical equipment or any crew or any trucks or vehicles.

LEARY: Our next tour is going to be a wax museum. You could smoke a fake joint with your favorite wax rendition of the Butthole Surfers backstage.

COFFEY: Wow. That looks just like King Coffey!

So what do you guys plan on doing in the future?

COFFEY: I think we’ll direct.

—————————————————

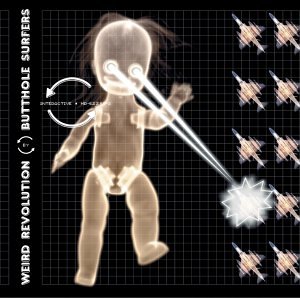

BUTTHOLE SURFERS RETURN FOR ‘WEIRD REVOLUTION’

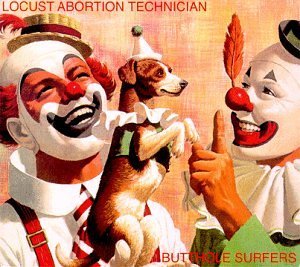

Lovable degenerates when they debuted with ‘83s constipated mindfuck, Brown Reason To Live, Austin, Texas-based Butthole Surfers heightened their avant-dementia by ‘87s cacophonous Locust Abortion Technician. After a five-year layoff due to protracted legal battles with former label, Capitol Records, these boho mofos return to action with the less twisted, but equally lysergic Weird Revolution. As with ‘93s Independent Worm Saloon and ‘96s mainstream breakthrough, Electriclarryland, the Buttholes latest venture may lack the colossal mayhem and grizzled debauchery of timeless EP’s such as ‘84s Live PCPPEP and ‘85s Cream Corn From The Socket Of Davis, but the inventive fury of its mutated triumvirate remains solidly intact and wholly committed.

Lovable degenerates when they debuted with ‘83s constipated mindfuck, Brown Reason To Live, Austin, Texas-based Butthole Surfers heightened their avant-dementia by ‘87s cacophonous Locust Abortion Technician. After a five-year layoff due to protracted legal battles with former label, Capitol Records, these boho mofos return to action with the less twisted, but equally lysergic Weird Revolution. As with ‘93s Independent Worm Saloon and ‘96s mainstream breakthrough, Electriclarryland, the Buttholes latest venture may lack the colossal mayhem and grizzled debauchery of timeless EP’s such as ‘84s Live PCPPEP and ‘85s Cream Corn From The Socket Of Davis, but the inventive fury of its mutated triumvirate remains solidly intact and wholly committed.

The three-headed monster consisting of singer-keyboardist Gibby Haynes, guitarist Paul Leary, and percussionist King Coffey (each involved with their own side projects and/ or production work) continue to improve upon technical skills and computer experimentation. While Weird Revolution’s underworld provocations and cultural future shock may be less outre, stark, and grimy than ‘86s railing Rembrandt Pussyhorse (and its thematic scheme undeniably more discernible and closer to the surface), the Butthole Surfers still ‘out-freak the normal man’ as infernal ‘messenger(s) of strangeness.’

Lanky, ratty-looking frontman, Gibby Haynes, gets on the soapbox for the Zappa-esque title track, then provides a scuzzy frog-throated rap on the truly accessible “Shame OF Life” (co-written with Kid Rock). He sounds downright pop-friendly on the ultra-catchy “Sweet Jane”-ish anthem, “Dracula From Houston.”

Sometimes irascible and short-tempered (at least with scurvy press types), self-proclaimed Grand Funk fan, Paul Leary, links resonating riffs, grinding axework, and swervy whirs of abstract noise to Weird Revolution’s sometimes unpredictable arrangements. And bald-headed calm-mannered King Coffey anchors the latest oeuvre with a bevy of sharp rhythmic detours and syncopated trip-bop electro-beats.

So the twisted geniuses who first received exposure with an abominable, tasteless admission, “The Shah Sleeps In Lee Harvey’s Grave,” now take on a Beirut bombing “Jet Fighter,” an “Intelligent Guy,” that’ll ‘rock me baby all nite long’ much like Steppenwolf promised in ’69, and a loopy spaceship-bound “Last Astronaut.” For kicks, they’ve appended the Mission Impossible II laser beam, “They Came In” to fill the tail end.

Last time I spoke to the Buttholes was during the morning after a sold-out Roseland Ballroom show in ’96. Despite a record label rep quashing a conversation concerning Gibby’s prior drug habit and Paul’s disgust at Capitol setting up such an early interview following a long night of drinking, the result was a fun-filled weed-laced hour with three of America’s weirdest revolutionaries.

More reserved and less volatile than last time we spoke, Paul Leary offered thoughts on terrorism, current musical influences, and his combo’s latest disc.

The title, Weird Revolution, is ironic considering the World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Since you’ve touched on topical social issues such as the Gulf War on your early ‘90s solo album, History Of Dogs, what’s your take on the current tragedy?

PAUL: I think there’s aliens inside the moon wondering when they should step in and straighten this mess out. (laughter)

What do you think about fellow Texan, G.W. Bush?

Gosh. Do we have to claim him? I don’t know. I wish people would get more introspective and figure out why this stuff happened. We could go bomb the shit out of whoever, but there’s reasons for everything. That’s the sad part. New York got shit on for the way we, as a country, all are. It’s a hate crime. But we have to put ourselves in their position no matter how strange and outrageous that is. But it doesn’t solve the problem. Why do they feel the way they do? It turns my stomach to see how many SUV’s are driving around. The price of gas went down so everyone goes out and fucking buys as much as they could instead of trying to ween ourselves off dependence to the Middle East. Who’s the enemy? At least in Pearl Harbor we knew who did it. What’s next?

A computer war where the U.S. wins. In fact, the Buttholes have implemented that advanced technology to Weird Revolution.

Digital recording is in its early phase. The way we recorded twenty years ago and the way it’s done now makes for a whole new creative realm.

You seem to use more technical guitar skills rather than meaty fast-fingered riff patterns.

It’s a compelling process that sucks you in. We’re getting mixed reviews. Some like it, some don’t.

There’s a strange dichotomy working. This is your best sounding and most accessible album, but avant-garde fans may fell it’s less Dadaist and less eccentric than past endeavors. Still, Electriclarryland had already moved in a more centrist manner.

We’ve always been intrigued by pop music. Look at the Cult’s “Sanctuary.” That was a pop song but it’s still cool today. It was one of the best mixes with a real monstrous kick drum. Now, everyone has monstrous kick drums.

The Buttholes early ‘80s stuff was far more demented, lo-fi, and underground.

There are influences now that weren’t in effect back in the days. Back then, we made records without any outside influences. There was nobody standing over shoulder, going ‘Gee. You should do this.’ Now, we have our songs and the first question is ‘Do we have two radio hits on it?’ We keep going ‘til we get it.

Not that it’s all reliant on commercial considerations. The title track seems influenced byFrank Zappa’s Lumpy Gravy or 200 Motels.

Uncle Meat was my favorite. Hip-hop has influenced us for awhile. Overall, I’m more guided by Glenn Miller. I love that stuff. He’s a true American hero. (Note: Swing Jazz pioneer, Miller, performed for WWII troops and died in a mysterious plane crash) I get laid listening to that music.

How ‘bout Benny Goodman?

I haven’t been listening to that, but I need to. I’ve been listening to Nat ‘King’ Cole and Texas Swing by Bob Willis.

Yet you’ve also produced adventurous rockers like Sublime, and recently, the Long Beach Dub All Stars. What did you add to their sound?

Because I know those guys, they have an awful lot of trust in me. The Dub All Stars music gives me a vintage feeling. Their songwriting is a throwback rather than new alternative. I wanted their record to be a collection of songs in an old-fashioned sense. Production is a utilitarian thing. You show up in the studio, work on songs, edit it, and mix it. It was mixed on an old AMAC board in Redondo Beach at Total Access Studio. We recorded some stuff with Spot there in ’82. So it was funny walking in that place again.

Was the Butthole debut EP, Brown Reason To Live, recorded there?

No. We owed Spot a few hundred bucks and we were too poor to pay. He ended up with the tapes and we re-recorded them in San Antonio. I’d love to get my hands on those tapes. It’s pretty funny stuff. Back then, most bands in the punk scene were on their own tangent. Now, we’re in a place in music where we were during the mid-’70s, when there were all these conceptions that had become solidified. It had become stifling. You keep expecting someone to breakout and tear the whole thing down again. I wouldn’t mind seeing that right now. Rock radio is hard to listen to these days. I don’t know what the business structure is to keep it the way it is, but it’s not in touch with what people want to hear. Hopefully, they’ll rebel and come up with something that puts those motherfuckers out on their asses. Look at the independent promotional business. That’s gross and still is. That’s how you get on the radio.

Did the four-year layoff since the Buttholes divorce from Capitol Records allow the band time to tweak with Weird Revolution?

The first couple years were spent in shock. We couldn’t believe we had our asses handed to us. We had a big hit with “Pepper” and a successful album. We thought we were good to go next time around. All of a sudden, we weren’t musicians anymore and were living in a world of shit. Once we got settled with Hollywood Records, we were able to access what we were working on and put a fresh perspective on it. (Co-producer) Rob Cavallo had ideas of what he wanted to do and the last bit of tweaking was hard work. Rob wanted radio songs and didn’t consider the album done until “Dracula From Houston” and “Shame Of Life” were included. He did a lot of work with those songs and put us in a situation to get this done – bless his heart. The next album will be a radical departure.

Take one of the best rhyme flowing freestylers, hook him up with an equally talented hip-hop producer, mix and match delicious beat samplings, and stir sufficiently throughout the course of a decade. The result: Atmosphere – a premier Minneapolis underground rap alliance initially revealed on a few impressive homespun cassettes.

Take one of the best rhyme flowing freestylers, hook him up with an equally talented hip-hop producer, mix and match delicious beat samplings, and stir sufficiently throughout the course of a decade. The result: Atmosphere – a premier Minneapolis underground rap alliance initially revealed on a few impressive homespun cassettes. Two years hence, Slug’s satirically fronting on the retro-spirited You Can’t Imagine How Much Fun We’re Having – head nestled wearily in hand for the plaintive cover shot. His character sketches absolve psychos, barflys, and fall guys, the same maladjusted individuals that’ve always been the source of his crustiest ruminations. Perhaps a little too reliant on Ant’s old school breakbeats and turntable scratching for mod rap heads (mentioning extinct inspirations such as 2Pac and the Moonwalk), it nevertheless overflows with the same contemporaneously fast tongue-tied anxiety of yore.

Two years hence, Slug’s satirically fronting on the retro-spirited You Can’t Imagine How Much Fun We’re Having – head nestled wearily in hand for the plaintive cover shot. His character sketches absolve psychos, barflys, and fall guys, the same maladjusted individuals that’ve always been the source of his crustiest ruminations. Perhaps a little too reliant on Ant’s old school breakbeats and turntable scratching for mod rap heads (mentioning extinct inspirations such as 2Pac and the Moonwalk), it nevertheless overflows with the same contemporaneously fast tongue-tied anxiety of yore.