FOREWORD: Dirty Three were an Australian instrumental trio whose poignantly Classical-inspired Chamber pop piqued the interest of more adventurous post-rock explorers. Live, at Tramps in Manhattan, they played their intensely moving tunes and followed them up with some welcome, but unexpected, comic relief in the form of dirty jokes, disgusting fake song titles, and audience baiting routines. Fuckin’ great stuff. They followed up ‘03s She Has No Strings Apollo with ‘05s lesser-known Cinder. Dirty Three’s members have backed up Nick Cave and Cat Power since then. This article originally appeared in Auqarian Weekly.

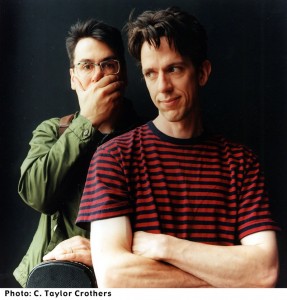

Poignant wordless emotionality, provocative sadness, and beautiful ethereal imagery define the solemn neo-Classical requiems prescribed by Melbourne, Australia’s debonair instrumental trio, Dirty Three.

Fronted by violinist Warren Ellis, this investigative ensemble has made five illustrious albums while its individual members concurrently appeared on a bevy of recordings by independent-minded artists such as Will Oldham, The Cruel Sea, Tex Perkins, Ute Lemper, and Black-Eyed Susans. An admirer of bluegrass and traditional Scottish-Irish music, Ellis studied piano and accordion as a child, learning standards such as “I’ve Got A Lovely Bunch Of Coconuts” and “Roll Out The Barrel” as a pre-teen in school.

In the early ‘90s, following a stint in unheralded These Future Kings, Ellis met guitarist Mick Turner, formerly of respectable punks, the Moodists, and drummer Jim White, who’d collaborated with Turner in local legends, Venom P. Stinger. Turner and White brought punk’s independent creative aesthetic to the delicate Baltic melodies and plaintive Celtic influences Ellis discovered as an impressionable youngster.

As Dirty Three, they’ve released ‘94s startling self-titled debut, ‘96s chaotic amble, Horse Stories, and ‘98s acoustically pure Ocean Songs to the delight of open-minded alt-rock intellectuals. By ‘00s more efficient Whatever You Love, You Are, their reflective moribund dirges were getting increasingly complex, leading to the pristinely jumbled pulchritude of ‘03s diligent She Has No Stings Apollo.

I caught up with Ellis via phone while he was doing laundry in France during a hailstorm before an evening show. The band will be featured in an upcoming concert film and Ellis hopes to recruit a large ensemble of diverse instrumentalists for unspecified future concerts.

I caught up with Ellis via phone while he was doing laundry in France during a hailstorm before an evening show. The band will be featured in an upcoming concert film and Ellis hopes to recruit a large ensemble of diverse instrumentalists for unspecified future concerts.

Compare US audiences to their European counterparts.

WARREN: Each country is an entity unto itself. Italy – we get a good response, but Germany, we don’t have much of a following. In the States, we probably have our best following.

I thought Europe’s 500-year Classical music history would make Dirty Three more popular there.

WARREN: Eight years ago, when we left Australia, I would’ve thought the same thing. We’re set up better in the States with Touch & Go and booking agents.

I was surprised you made hilarious off-color comments between each serious piece Dirty Three played at Tramps in ’98 to loosen up serious-minded fanatics.

WARREN: It breaks up the tension. I find our songs uplifting. I feel good after we play. I’m not depressed.

Tell me about Dirty Three’s pre-debut cassette, Sad & Dangerous.

WARREN: We recorded that in Mick Turner’s living room so we could remember the songs. At that stage, we wouldn’t have had our act together enough to send it to people and put out. A record store employee sent it to America and told us they wanted to release it on vinyl. We did things on the fly then. I got invited down to a pub where Kim Salmon (of Aussie icons the Scientists) had Monday night residency. He had this melody (which became the eponymous debut’s “Kim’s Dirt”) he played in my kitchen and when Dirty Three had its first show we worked out a bunch of songs. When he heard us do that background music that night he said we should take it.

Apollo’s song titles seem ironically satirical. The twinkly piano delicacy, “Long Way To Go With No Punch” seemingly boasts of lacking a climactic punch line.

WARREN: Titles could be spot-on or red herrings. Like Bob Dylan, who hides his greatest songs on Biograph or bootlegs, we try to mislead people. If you listen closely to this album, there are many different layers and it’s adventurous. We’re playing tighter than ever. We recorded it after touring with these songs we didn’t quite know. It put the fear of God in us again playing live and made the songs stronger. We’d recorded 20 songs from 35 or 40 ideas and worked down to seven, hammering them out onstage.

“Sister Let Them Try To Follow” takes joy in daring listeners to keep up with its heady arrangement, as guitar and violin move in separate distinct patterns above freeform drums.

WARREN: Yeah. It’s a lesson for the young kids. Don’t fucking come anywhere near us. (laughter)

“No Stranger Than That” seems flippantly influenced by Western music.

WARREN: That’s solely inspired by Hungarian violinist Felix Lajko, probably the greatest living violinist. It’s a tip of the hat to the master.

You should consider doing film work.

WARREN: We did the soundtrack to an Australian film, Praise, It’s based on a successful book and the film came together well. We were offered to do an HBO documentary score on serial killer doing art in prison. We had a dilemma. People offered strong opinions. We felt the images were so strong people related to our songs in such a personal way that we left it at that and didn’t want corpses being dug up while we’re playing.

Do your songs build from improvisations?

WARREN: It depends which record and what year. We started from small, humble beginnings, taking anything as far as we could. After years in pubs, we learned how to play better as a group. With each album, we’ do something different as a matter of maturing. There’s no divine intervention. We’re just banging away. I tried to work more parts into what I was playing on Whatever You Love. And Ocean Songs was a lesson in dynamics, trying to create intensity with no amps. Horse Stories was a giant, ugly fuck you to the world.

The hushed ambiance of In The Fishtank, Dirty Three’s captivating one-off collaboration with Low, peaks with Mimi Parker crooning Neil Young’s “Down By The River.”

WARREN: We had done a double headlining tour with Low for Ocean Songs. They’ve been friends for ages and invited us to play without working anything out. We met outside an Amsterdam farm studio for two days and captured the whole atmosphere. It was effortless, enjoyable, and certainly influenced how we play.

People compare your trio to early ‘90s slo-core band, Slint.

WARREN: I obviously know the band, but I don’t know what slo-core id. The problem with labeliong music is people go, ‘I don’t like that.’ Or maybe, ‘I don’t like Jazz.’ But there’s much good Jazz. John and Alice Coltrane, Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman. We’re still discovering them. I also like Classical composers Eethoven, Shastokovitz, Haydn, and Bartok. In the rock field, I like early AC/DC and Neil Young.

Your playing on Nick Cave’s solemn No More Shall We Part seemed to prominently affect his devotional songs.

WARREN: Nick could go pretty deep on his own. I helped write string arrangements with Nick Harvey on that. But I don’t listen to things I do so it’s hard to be judgmental. I listen when I’m done to see if it’s all right. The new one I listen to quite a bit because it continually surprises me. We worked hard at this and it was difficult. We were grateful afterward.