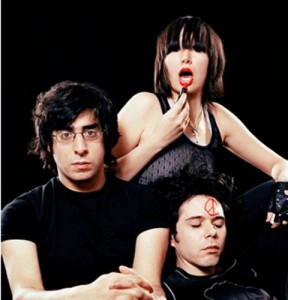

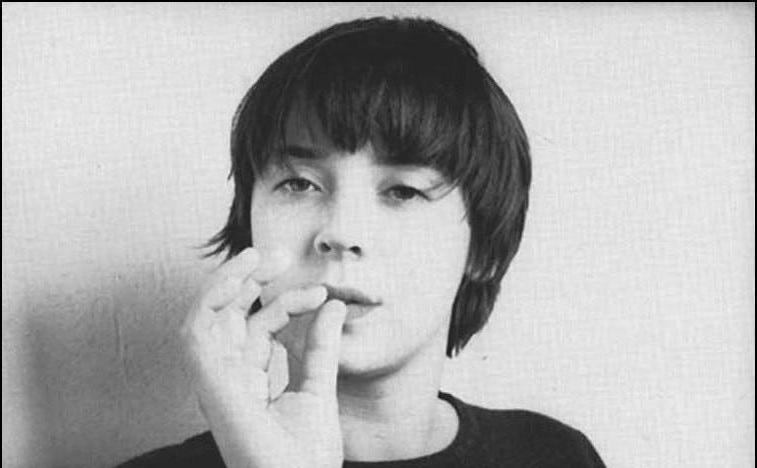

FOREWORD: Can the white man sing the Blues? If you’re Roxy Music fan, Stuart Staples, the answer is an unequivocal yes. Speak-singing in a deeply resonant baritone, Tindersticks amiable frontman takes inspiration from Gospel-derived R & B legends and blends it into his bands’ lush orchestral settings.

I originally interviewed Stuart for HITS magazine in ’97 to promote the brilliant Curtains LP. In ’01, I met the band for dinner at Manhattan’s Time Café (with my friend, Rich Farnham), to support ‘01s even better, Can Our Love… We had a few laughs, gave Stuart shit about his stoic singing voice, and made innocently tasteless remarks about passersby. In ’09, Tindersticks returned with the intriguing Falling Down A Mountain. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Already admittedly informed by brooding crooners Neil Diamond, Leonard Cohen, and Frank Sinatra, Tindersticks frontman Stuart Staples has also developed into quite a serious Soul junkie lately. Following two eponymous albums of idiosyncratic folk-inspired cabaret, sublime Jazz-noir, and stark Chamber pop, this Nottingham, England, sextet continued their ascent with ‘97s beautifully draped Curtains. But due to an expired contract with their former label, ‘99s groundbreaking Simple Pleasures (influenced by ‘60s Rhythm & Blues from the Stax/ Volt vault) never reached US shores.

Happily, the indelible Can Our Love… further explores the soulful essence of its predecessor, stepping forward with moody orchestrations inspired by ‘70s Blaxploitation soundtracks such as Isaac Hayes’ Shaft and Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly while conjuring distant memories of Marvin Gaye’s “Trouble Man,” Bobby Womack’s “Across 110th Street,” and Joe Simon’s “Cleopatra Jones.”

Staples’ equally gifted partner, violinist/ pianist Dickon Hinchliffe, provides sweeping string arrangements to morose, suspenseful fare (the sullen “Dying Slowly,” the weary “People Keep Comin’ Around,” and the almost nightmarish “Sweet Release”) and the blissful serenity of Staples’ fertile poetic lullabies (the guarded “No Man In The World” and the warm-hearted “Don’t Ever Get Tired”).

Named after the famous ‘70s Chicago R & B group, “Chi-Lite Time” lathers Hinchliffe’s viola across burbling synth and a dirge-y beat for an epic-length closer worthy of its titular auspices.

At a sold out Bowery Ballroom show in July, Staples’ low-toned, cigarette-stained baritone brought haunting melancholia and barren sadness to Hinchliffe’s sympathetic settings. Staples’ dark revelations rang true with the same emotional tranquillity, flickering romanticism, and elaborate eloquence the respected crooners he admired once had. And when he clipped otherwise lingering, stretched syllables, his artful mannerisms recalled Bryan Ferry (which felt ironic since he planned on attending a Roxy Music show at Madison Square Garden after my interview at Time Cafe the night before).

How has Tindersticks advanced musically over the years?

STUART: We keep evolving. Looking back, after Curtains we wanted to find new ways to write songs and break things down. Simple Pleasures had a certain consciousness about it.

DICKON: It was planned meticulously and was well rehearsed. But for Can Our Love… we went into the studio to see what happens instinctively.

Why choose ‘70s soul to emulate this time out?

STUART: It’s not like we went back to ‘70s soul because we didn’t know what to do. We were growing. These are very melodic songs with rhythmic appeal. Curtains was such a complicated record with great big epic length songs. The records we listened to in order to get away from that were these simple Al Green records. We wanted to find that kind of simplicity and boil down the essence of six people. The influence of soul captured a feeling. We were pushing forward and we all enjoyed making Can Our Love… But some of those songs were originally 12 minutes long and were then edited down.

Tindersticks have continued to become more unified with each succeeding record.

STUART: We started off with no technique. Now there’s more of a flow to our music. Songs like “Sweet Release” are real personal, but everyone has those feelings.

Besides the usual crooning suspects, I’ve read Neil Diamond also influenced the tormented love songs you write?

STUART: He was one of my biggest influences, but not through choice. My mother, from when I was born until age ten, listened to him, Perry Como, and Jack Jones. It also has a lot to do with my sister. She’s four years older and in the late ‘70s I got all her music. She was a Northern Soul girl. That took over after my mom’s crooners until punk rock came along.

How about you, Dickon. Who influenced your style of arranging strings and playing violin?

DICKON: I’ve been playing violin since I was young. I suppose Sugar Cane Harris was an influence and the woman who played on Bob Dylan’s Desire (Scarlet Rivera). The arrangement skills came a little later for our second record. With the first album, we layered tracks of violin and viola. Then, I realized it would be better if a lot of people played. I’ve always listened to the arrangements of Nelson Riddle, Johnny Pate (Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly arranger), and Billy Strange.

What’s with the open-ended album title Can Our Love…?

STUART: I suppose the abbreviated song title grew into the album title in order to leave it open for interpretation. We didn’t want to pin things down too much with a description.

This album nearly parallels the recent stylings of Kurt Wagner’s Southern-based band Lambchop – minus the Countrypolitan influence.

STUART: Our first albums both came out very close to each other independently. They were long, sprawling works. Then, we made Simple Pleasures at the time they made Nixon. Something is kind of happening there. I am a fan. Lambchop has done very well in England.