Singer-songwriter Matt Ward grew up in Ventura County a few miles north of Los Angeles. A big Beatles fan, he picked up a guitar at fifteen and began toying with a four-track thereafter. His short-lived project, Rodriguez (with Little Wings’ unheralded Kyle Field), offered an opportunity of a lifetime. During an opening performance, Ward impressed Jason Lytle, guiding light of defunct Modesto-based bellwethers, Grandaddy. This led to Lytle producing their lone album, Swing Like A Metronome. Ward received some local recognition and before long moved to Oregon.

Singer-songwriter Matt Ward grew up in Ventura County a few miles north of Los Angeles. A big Beatles fan, he picked up a guitar at fifteen and began toying with a four-track thereafter. His short-lived project, Rodriguez (with Little Wings’ unheralded Kyle Field), offered an opportunity of a lifetime. During an opening performance, Ward impressed Jason Lytle, guiding light of defunct Modesto-based bellwethers, Grandaddy. This led to Lytle producing their lone album, Swing Like A Metronome. Ward received some local recognition and before long moved to Oregon.

Residing in Portland, he met Howe Gelb, founder of desert-rock oddities Giant Sand. He gave the ageless patriarch a self-recorded demo during a Seattle stint. Soon, the now-christened M. Ward made his formative fingerpicked debut, Duet For Guitars #2, on Gelb’s boutique Ow Om Records. An ’01 follow-up on Future Farmer, End Of Amnesia, led to Ward’s signing with foremost Carolina label, Merge Records.

On ‘03s unalloyed breakthrough, Transfiguration Of Vincent, Ward’s understated minimalist tunes, frequently delivered in a sheepishly intimate tenor, proved to be captivatingly therapeutic confessionals with convincing introspective insight. His scruffy prairie wanderings and somber campfire retreats had the intrinsic pastoral beauty of what fellow Portland artist Stephen Malkmus once coined the “Range Life.”

A delicate folk charm resonates from Ward’s hushed cigarette-stained baritone identity, actualizing the forlorn bellow of a drowsy grief-stricken loner straddling the precipice time. Betwixt haunting romantic lamentations lurk plain Western preludes, interludes, and prologues; fastidious instrumental tracks that’d also bedeck the ensuing Transistor Radio.

Still singing in an artlessly unaffected monotone drone, but utilizing cleaner production, better songs, and a more relaxed atmosphere, Ward doubled his spellbound audience with Transistor Radio. Rooted more in rural folk-blues tradition and solemn old timey ballads, its highlight has to be the wistful “Radio Campaign,” where Ward serendipitously repeats the choral ‘come back my little piece of mind’ with the same uncanny tossed-off slacker delivery inevitable pal Conor Oberst emitted for Omaha counterparts, Bright Eyes.

Tempered piano boogie ditty, “Big Boat,” turns up the bass turbines and lays on the slashin’ cymbals. “Hi-Fi” welcomes the purified bossa nova elegance Ward’s apt to dabble in. And “Four Hours In Washington” works as an insomniacs twisted nightmare offhandedly presaging another indirect Capitol City homage, Post-War.

Concerning personal politics in spite of its expediently combative Middle East-affected epithet, Post-War scuttles opportune anti-militaristic effrontery by way of a tactful procession of desperate lovelorn limericks swept away when the cagey Ward tackles cracked Texas eccentric Daniel Johnston’s rejuvenating, “To Go Home.” A rustic homecoming with a prescient Neko Case vocal cameo, its dark piano grandeur and plodding bass inexplicably evoke semi-famous Montreal contemporaries Arcade Fire. As usual, Ward’s powerful interpretive ability makes it possible for him to push across Johnston’s triumphal lyrics with preferable candor.

Concerning personal politics in spite of its expediently combative Middle East-affected epithet, Post-War scuttles opportune anti-militaristic effrontery by way of a tactful procession of desperate lovelorn limericks swept away when the cagey Ward tackles cracked Texas eccentric Daniel Johnston’s rejuvenating, “To Go Home.” A rustic homecoming with a prescient Neko Case vocal cameo, its dark piano grandeur and plodding bass inexplicably evoke semi-famous Montreal contemporaries Arcade Fire. As usual, Ward’s powerful interpretive ability makes it possible for him to push across Johnston’s triumphal lyrics with preferable candor.

On the instrumental front, there’s the majestic “Neptune’s Net,” a reverberating Hawaiian surf guitar orchestral. And without making too much of a fuss, celebrated My Morning Jacket bard, Jim James, contributes tender backup vocals to dreamy elegy, “Chinese Translation,” as well as snickering acoustic trifle, “Magic Trick.”

As a nostalgic sidestep, Ward’s striking ’08 collaboration with Hollywood actress, Zooey Deschanel, a reluctant piano-playing singer-songwriter, caught the attention of grass roots enthusiasts as well as the pop masses. Under the trite moniker, She & Him, the resourceful pair have a good time embracing innocent Country-blues eclecticism, endearing Deschanel’s uplifting bell-toned contralto to Ward’s meditative six-string adaptations. Dusty Springfield’s friendly ghost hovers above the lilting whistled symphony, “Thought I Saw Your Face Today” and Patsy Cline’s wayward drama compels the moving Country & Western torch song, “Change Is Hard.”

Redemption and hope consume ‘09s prodigal Hold Time, originating with hastened acoustic deliverance, “For Beginners,” which peers down from Mount Zion in search of salvation. Perhaps aching for spiritual guidance, “Jailbird” finds Ward summoning supreme powers to ‘help me, help me now’ over nectarous orchestral strings and Spanish guitar. The resolute “To Save Me” spells out his philosophical beliefs inside an approachable, upbeat, echo-laden Wall of Sound re-creation employing streamlined piano and nifty Beach Boys harmonies.

The seemingly secular fare brings further dramatic impact and added coloration. Glistened keyboard burbles go asunder as oncoming six-string, bass, and drums awaken chimed horoscopic summit, “Stars Of Leo.” Spaghetti Western guitar and a down-along-the-railroad bass scheme suitable for Johnny Cash (yet somehow indicative of Buddy Holly’s Texas two-step rock and roll) reinforce the folkloric ode, “Fisher Of Men.” And the same hand-clapped kick-drummed snare beat embedding Gary Glitter’s ubiquitous glam anthem “Rock & Roll Part 2″ secures love-struck jubilation, “Never Had Nobody Like You.”

The seemingly secular fare brings further dramatic impact and added coloration. Glistened keyboard burbles go asunder as oncoming six-string, bass, and drums awaken chimed horoscopic summit, “Stars Of Leo.” Spaghetti Western guitar and a down-along-the-railroad bass scheme suitable for Johnny Cash (yet somehow indicative of Buddy Holly’s Texas two-step rock and roll) reinforce the folkloric ode, “Fisher Of Men.” And the same hand-clapped kick-drummed snare beat embedding Gary Glitter’s ubiquitous glam anthem “Rock & Roll Part 2″ secures love-struck jubilation, “Never Had Nobody Like You.”

Part of Ward’s success thus far could be attributed to his aspiration to “keep feeling like I’m making my first album each time out.” That perseverance has paid off.

Do you see a thread connecting the lean John Fahey-like guitar pickings of your earliest endeavors to the latest generously arranged symphonic works?

M. WARD: The record’s have more in common than there are differences. They all fit together because I have no perspective. I’m still inside this long tunnel. I love the process I’m inside of – as far as making records goes. There’s enough variance for me to keep it stabilized and not make any drastic changes. I know the Rolling Stones could fly to Jamaica to make a record in ten days. For me, it takes two years. It depends on the passage of time to tell me which things to harvest and what to keep in the manure.

You seem to be incorporating the instrumental guitar passages into vocal songs more often. And the songs seem more hopeful.

I feel like a good record should feel like a good movie. People should be able to laugh and cry at the same experience. Every song is a balancing act between light and shadows. Hopefully the balance is somewhat representative of the happiness and sadness in your life. I grew up listening to the Beatles’ White Album. I never looked at records as needing to be in one steady mood or chord progression. The records are a chance to see how far you could take these different emotions. I keep them tied together. I’m just using the voice to carry a story across a melody. I still look to the guitar to take the listener to those incredible Roy Orbison moments where vocals reach operatic heights. I gravitate towards the guitar to make those statements.

You’ve increasingly used heavier beats on each successive album, culminating in Hold Time.

In general, I wanted to take the rhythms and the sounds of Post-War and basically dissect it and make rich sounds richer and thin sounds thinner as an experiment to see if they could live within a song.

Do you write the symphonic arrangements?

Yeah. I started on Post-War. It’s a newfound joy for me to be able to write string arrangements and see them come to life. Strings are such a touchy element of production because it’s easy to go over the top and make something sappy. But with enough vinegar you could keep something sweet from being saccharine.

On the other hand, there’s the spare Robert Johnson-styled lowdown folk-blues of “One Hundred Million Years.”

Absolutely. I still have a great fascination with old Robert Johnson records. That simplicity I love in equal measure to the big Phil Spector/ George Martin productions. To see if they could live together on the same record was an experiment worth pursuing.

Renowned Western-folk minstrel Lucinda Williams sings descant on your whispered dirge-y version of Don Gibson’s “Oh Lonesome Me.”

During the production of that song I started to hear her voice. I had never met her. But when asked to do a duet she said yes. Since I was in high school she’s been an influence, especially Happy Woman Blues. To have her voice on my record is a great thrill. Lucinda’s voice, in some ways, reminds me of Billie Holiday. It’s raw. She was a joy to work with.

How did your project, She & Him, with Zooey Deschanel, come into fruition?

We both grew up listening to KROQ, a groundbreaking L.A. radio station. In the ‘80s, they introduced me to British bands, Sonic Youth, and SST bands. Zooey’s an incredibly talented person. She & Him is entirely different from my solo stuff. I take a backseat and let her sing. Her influence is felt on the Hold Time record, too. We plan to do Volume 2, which is in the demo stage presently.

You construct a narcotic version of Buddy Holly’s “Rave On” with Zooey doing background vocals.

Buddy Holly’s writing has been an influence since day one. I discovered him through the Beatles, realizing later how they didn’t write some of their earliest songs I grew up and learned guitar on. That was a revelation. It’s the simplicity I love most about his writing. The mystery that keeps his songs so durable is something I can’t put a finger on.

How much did the Gulf War and contemporary conservative politics affect Post-War?

It’s the time I was in, but not necessarily where my head was in. I felt a similarity between New York Times articles I’d read and my favorite books about previous wars. Part of the fun about making a record is you get to play with time and space. It’s gonna mean something different to everyone. There were different interpretations for the new record. I wanted to breakdown time more and not have a specific or vague backdrop. That’s part of the reason I like having cover songs inside a record, to breakdown any chronological time the listener may feel they’re in.

Why does Portland house so many literary songwriters? There’s the Decemberists, Modest Mouse, and Thermals.

It must be the coffee. (laughter) Over the last decade, Portland’s no doubt the cheapest West Coast city. Affordable rent makes it easier to do what you love. L.A.’s only a two-hour flight. In San Francisco, you’d have to live in a roach motel. It’s open-minded and you could create without the pressure of too much or not enough media.

M. Ward headlined the Apollo Theatre on February 19th, 2009.

Circus-like Man Man bandleader, Honus Honus (born Ryan Kattner), is the perfect pied piper, a worldly troubadour adrift in strange towns on a never-ending vagabond journey, perhaps suffering privately to assemble pensive lyrical twists and scatological musical turns executed like some ravaged Blues-croaked Captain Beefheart disciple.

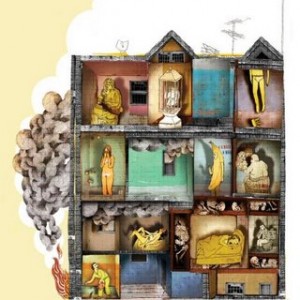

Circus-like Man Man bandleader, Honus Honus (born Ryan Kattner), is the perfect pied piper, a worldly troubadour adrift in strange towns on a never-ending vagabond journey, perhaps suffering privately to assemble pensive lyrical twists and scatological musical turns executed like some ravaged Blues-croaked Captain Beefheart disciple. But as much nonconforming fun as Six Demon Bag proved to be, the taut collective improved twofold for maniacal abstraction, Rabbit Habits (Anti Records), a magnanimous follow-up finding Honus perched somewhere between cultish beatnik bard, Tom Waits, and some dingily nebulous swamp-rooted vagabond. At times, Honus Honus’ troupe seems to nip at the heels of gypsy punk, as on “Easy Eats or Dirty Doctor Galapagos” and fascinatingly playful snub, “Top Drawer.”

But as much nonconforming fun as Six Demon Bag proved to be, the taut collective improved twofold for maniacal abstraction, Rabbit Habits (Anti Records), a magnanimous follow-up finding Honus perched somewhere between cultish beatnik bard, Tom Waits, and some dingily nebulous swamp-rooted vagabond. At times, Honus Honus’ troupe seems to nip at the heels of gypsy punk, as on “Easy Eats or Dirty Doctor Galapagos” and fascinatingly playful snub, “Top Drawer.”