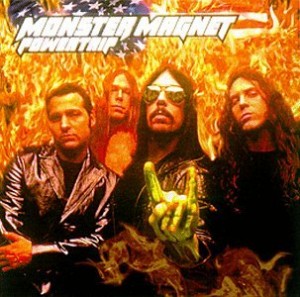

FOREWORD: I first saw jolting Jersey jammers, Monster Magnet, play live at Irving Plaza in the mid-‘90s. I was amazed by the flexible gumby-like bodily contortions singer-writer Dave Wyndorf could manage while still spitting out venom inside metal-edged arena rock tunes.

After some ’89 demos and a cheap Glitterhouse Records EP, these evil space rockin’ metal-plated combatants made ‘92s undeniable stoner rock doctrine, Spine Of God. But in all honesty, it wasn’t until ‘93s Superjudge that I became aware of Monster Magnet. ’95s Dopes To Infinity made me a fan for life.

So when it came time for me to interview Wyndorf at a discreet Manhattan pub to discuss his bands’ latest endeavor, Powertrip, I was stoked. While he smoked cigs and I plowed beer, I listened and marveled at his boho idealism and then sent the following article to a topnotch girlie mag.

After Powertrip, Monster Magnet’s ’01 LP, God Says No, kicked harder ass than ‘04s better-titled Monolithic Baby! In ’06, Wyndorf overdosed on prescription drugs but came back to the fold for ‘07s 4-Way Diablo. In ’04, guitarist Ed Mundell’s side project, Atomic Bitchwax, found favor with High Times stoners at midtown Manhattan-based Doobie Awards. This article originally appeared in Gallery Magazine.

During a Las Vegas jaunt, Monster Magnet singer Dave Wyndorf spent two weeks leering at strippers, observing gamblers, and writing (from the confines of his hotel room) the 13 muscular, full-throttled tracks served up on Powertrip – the bands’ fourth album.

Like a nomadic warrior trapped inside a hard rock war zone, Wyndorf taps into the unbridled sexual energy sapped from the soul of rock and roll.

“The rappers do what they want in Vegas. They get the chicks, the money, and the guns. I loved watching them. They were like a bizarre dream. They own rock and roll,” Wyndorf admits. “But the rockers have given the press very little to write about besides Marilyn Manson. Much of what’s picked up by national radio stations is disposable, artificial and slick. It’s all just manufactured energy.”

Since the late ‘80s, rock radio has saturated the market with overblown heavy metal practitioners (is that a dirty word?) such as Posion, Motley Crue, Winger, Ratt, and glam-rokers Bullet Boys (including a legion of watered-down, forgettable, no-talent hair bands). It has been an uphill battle revitalizing the once thriving scene. When Nirvana hit the big time, grunge infatuated the impressionable teens that were once proud fist-waving metal heads.

Unscathed by such trends, Monster Magnet sough to incorporate psychedelia, punk, and a dash of sitar into its adventurous and ambitious metal-edged sound.

Wyndorf, who grew up 45minutes outside Manhattan in Red Bank, New Jersey, joined the punk-metal band, Shrapnel, before forming Monster Magnet and releasing several singles and EP’s during the late ‘80s. Monster Magnet exploded on the national scene with ’93 stoner nightmare, Superjudge, a grueling Mountain/ Black Sabbath-derived long-player with power (and weed) to burn. ‘95s more assured Dopes To Infinity found the group on the brink of worldwide success. But as they found out – achieving mass acclaim in the ‘United States of who gives a shit’ (a line taken from Powertrip’s cock tease “3rd Eye Landslide”) becomes a Catch 22 experience.

“Radio is afraid to lose sponsors and advertisers,” says Wyndorf. “MTV has already bowed down to Tipper Gore’s PMRC, an organization that manipulated the media. Now rock and roll rebels take it up the ass. The first sign of rock and roll losing its cultural power was when punk rockers started to clash with rockers (in the late ‘70s). That’s when rock fragmented and lead to further niche marketing. Most kids who are now in their twenties have no sex and take no drugs, but they’ll explode when they reach forty.”

He insists, “Miscommunication gives these kids an excuse to swerve off and internalize, avoiding real life and surrendering to asshole propaganda. When they gravitate towards conservatism, they’re admitting they’re afraid of life.”

Although Dopes To Infinity’s visceral slammin’ anthem, “Negasonic Teenage Warhead” was a radio hit in ’95, Wyndorf realized the drawbacks that conservative commercial radio programmers and multinational music conglomerates imposed on their multilevel exposure. Like most big corporations, they’d rather play it safe and appeal to an already dulled-out audience.

Still, Wyndorf seems fully capable of challenging the opposition by reclaiming rock and roll’s lost territory thanks to Powertrip’s defiant songs. An astonishing accomplishment and a fine sonic successor to Tool’s convulsive Aenima, its dramatic metal-blazed epics unleash frustration and anxiety with unbridled intensity. He insults emasculated politically correct slime with the snide declaration: ‘So won’t you put my dick in plastic and put my brain in a jar’ (taken from “Atomic Clock,” a corrosive knockoff of Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs”).

But he’s also not afraid to admit having to overcome his own shortcomings. The searing guitar freak-out, “Tractor,” refers to self-imposed pill rehab (‘I got a knife in my back and a hole in my arm when I’m driving my tractor on the drug farm’).

But he’s also not afraid to admit having to overcome his own shortcomings. The searing guitar freak-out, “Tractor,” refers to self-imposed pill rehab (‘I got a knife in my back and a hole in my arm when I’m driving my tractor on the drug farm’).

Voyeuristic fascinations also dominate the stampeding “Bummer,” a raunchy pre-metal spasm ridiculing vulnerable, narrow-minded Confederate Southern belles with scathingly sordid lines like ‘You’re looking for the one who fucked your mom…It’s not me.’

“While touring the deep South in ’96, I became aware of how the local girls were looking for someone like their father. It’s a bummer. They go after the image and feel guilty afterwards if they give in to sex. It comes down to taking emotional responsibility,” he explains.

The mescaline-fazed “See You In Hell” recalls the psychedelic daze of the conceptually naïve LSD-laced mind-trip “Incense And Peppermints” by Strawberry Alarm Clock (or quite possibly, Iron Butterfly’s “In-A-Gada-Da-Vida”). Its lyrics deal with downsizing preconceived notions of peace generation hippies of yore.

“On a bus ride, a hippie broke into this story about how his wife unintentionally had a baby, freaked out, and buried it in a Jersey swamp. It’s a total ‘60s horror tale. Hippies I met in the past were always confrontational and self-centered. They’d sell their girlfriends for speed,” Wyndorg explains.

Although he admits working in the studio on a new record is never a comfortable experience, instead calling it “controlled disaster,” Wyndorf does insist there is a method to his madness.

“First, I make four-track tapes with guitar, bass, vocals, and drum machine. Then, I bring them to the band (Ed Mundell, lead guitar; Joe Calandra, bass; Jon Kleiman, drums, Tim Cronin, visuals and propaganda) and have them critique the songs and possibly rearrange things. I like to start with a slow groove, then let it build to a fucking explosion. I usually abandon the songs at some point. Otherwise, I’d be refining them forever.”

While in Vegas, Wyndorf saw a rainbow of humanity. He’d see shiny happy people come in for the first time – psyched up and ready to gamble – only to be drained of all their money.

“That place is brutal. You’d see people come in one day, and by the next, they’d be getting dragged out, all washed up. But there was also a lot of honest emotional psychoanalyzing going on in my head. It made me realize that the best thing about Monster Magnet is that it’s all about rock. If I didn’t get to jump around onstage every few months, I’d be in an insane asylum.”

After the bands’ worldwide touring, Wyndorf sought seclusion away from the other Monster Magnet members and the wintry northeast. He headed for the heat and settle in the blazing Vegas desert in ’97.

“Las Vegas is the ultimate symbol of all the shit I was worried about concerning Monster Magnet’s place in the entertainment world, like maintaining a cool lifestyle. It’s where money, advertising, and imaging get scaled to the success of Titanic and Jurrasic Park. Monster Magnet was initially designed to appeal to just a few people, but now it is millions,” he says while lighting a cigarette.

“On Powertrip, I reacted on a gut level. Instead of trying to mastermind a record for the lowest common denominator – which would have neutered half the cool ideas – I tried to avoid mental breakdown by putting myself on a writing schedule. The more records I do, the closer I come to distilling a potent diary of my life experiences. I can’t fantasize, so I write what’s inside of me. I wanted to make Powertrip a very physical record that operated from the groin first, unlike Dopes, which was very cerebral. It has more action, tension, and spontaneity, not a lot of dreaming.”

As the sixth of eight children, Wyndorf admits he struggled to overcome a teenage identity crisis before becoming the virile entertainer his avid fans adore. He went through a weird gestation period, failing miserably when it came to picking up hot-to-trot chicks.

“But my love of music had a healthy, hypnotizing effect. I’d lock myself in a room with a bag of pot and listen to every obscure rock album like a total mutant,” he recalls, adding that the single most powerful force is when nature commands you to stare at girls’ asses.

“In Vegas, I’d go to strip clubs for the awesome temptation. As frustrated as I’d get, the more intrigued I’d become. And since I was raised Catholic, it teaches you how to become a dirty bastard. You have to overcome the guilt. It’s hard to put your trust in manmade organized religion.”

Now that grunge has died down and electronica has failed to take America by storm (as many had thought it would) maybe good old straight-up rock ‘n roll bands will become all the rage again. Who knows? Maybe leather jackets, biker boots, and long hair will replace nose rings, buzz cuts, and sneakers. If so, look for Monster Magnet at the top of the heavy metal heap.