FOREWORD: Okkervil River, whose unlikely moniker was taken from a book by minor Russian novelist, Tatyana Tolstaya, creates some of the most mellifluously maudlin lamentations in contemporary music. I got to speak to Okkervil River main man, Will Sheff, during ’04, right before Black Sheep Boy secured instant indie rock breakthrough. Even better, ‘07s The Stage Names assured protracted interest in the reliable outfit. As if to prove their worth, ’08s The Stand Ins heightened the uplifting, upbeat allure above the moodier downers. In ’09, they teamed up with drug-addled psychedelic rock progenitor, Roky Erickson, for the provocative True Love Cast Out All Evil. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Raised in woodsy rural New Hampshire by assertive teachers, singer-songwriter Will Sheff attended private school and listened to standard issue ‘60s hippie fare, discovering Neil Young, Bob Dylan, and Joni Mitchell through his mother before delving deeper into the so-called ‘acoustical’ archives. It seems a friends’ countercultural father turned this self-described “nerdy campus brat” onto the Incredible String Band, leading him to Newport Folk Festival blues icons Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James, and more pertinently, literary outlaw Leonard Cohen. After disappointingly attending Minneapolis-based Mc Allister College, Sheff decided to throw caution to the wind, passively rebelling against higher education by forming melancholic combo, Okkervil River, with a few friends back home.

Sheff explains the origin of his bands’ flowing moniker thusly. “We were at our bassists parents’ Austin-tacious pink mansion in rural Texas. It was the shape of a cross. So we’re in this bizarro circa-‘60s side room frustratingly throwing out terrible names. I was reading Russian literature and went nuts for this grand niece of Alexi Tolstoy’s story, called Okkervil River. But it had two k’s, ended with only one l, and there was no c. I thought we should’ve changed it to Dirge Overkill since people may otherwise think we’re a Country band sitting around the porch drinking moonshine.”

Soon settling in Texas musical mecca, Austin, Okkervil River struggled to land early gigs, finally recording ‘00s formative 7-song Stars Too Small To Lose prior to signing with notable indie label, Jagjaguwar. Initiated as a demo-styled EP, the superior full-length Don’t Fall In Love With Everyone You See brought Sheff’s coterie minor underground credibility.

“Stars Too Small To Lose was stark, simple, and should probably remain forgotten,” Sheff good-naturedly quips. “I’m happy with the songs and playing, but I don’t like my singing and the mastering. We’ve redone half the songs. As for Don’t Fall In Love, it’s mostly acoustic guitar, bass, and drums. Brian Beattie, an intuitive local producer, had New Hampshire relatives and may’ve approached us based on that. He helped us think about constructing arrangements and not all playing at once. That provided the enthusiasm to expand my ambitions. We tried to be lush, yet rickety, in an enjoyable way, pouring our hearts out learning to play.”

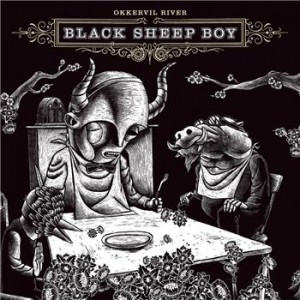

Minimalist San Francisco minstrel John Vanderslice then worked the boards for ‘03s truly accessible Down the River of Golden Dreams, which captivated high profile journalists and post-adolescent mope-rock devotees alike. Its startling pastoral imagery and mysteriously grotesque medieval intrigue matched the fascinatingly malformed artwork of William Schaff.

“Schaff’s an old friend I met through a drummer,” Sheff recalls. “He’s done art for Godspeed! You Black Emperor, Songs: Ohia, and Kid Dakota. We’d trade off making Kinko’s posters with collage clips. His aesthetic was the same as ours but effortless and memorable. I hope the art adds to my mystical approach. I’d given him increasingly detailed notes of what I wanted. Down the River focused on a water theme with its bizarre octopus-man creature.”

For ‘05s more abstruse Black Sheep Boy, Sheff felt extremely determined to further link Schaff’s disturbing images to the edgy revenge fantasies and prickly predicaments he’d designed. Sheff’s lucid intuitiveness draws inspiration from ancient post-modernist ideals, regaling in an epoch when paganism dribbled into Christianity’s vainglorious stronghold.

For ‘05s more abstruse Black Sheep Boy, Sheff felt extremely determined to further link Schaff’s disturbing images to the edgy revenge fantasies and prickly predicaments he’d designed. Sheff’s lucid intuitiveness draws inspiration from ancient post-modernist ideals, regaling in an epoch when paganism dribbled into Christianity’s vainglorious stronghold.

“I wanted to make an album which had all the songs written at the same time. It’s an attempt at straightforward wholeness. It’s also a coded account of the struggles we went through in 2004, a stormy year for me. I didn’t have a place to live, stayed on the road touring for half the year, and had some things in my life fall apart. So I wanted a messy, raw, intense record to match the times,” he claims.

Unrequited love filters the hushed “For Real,” bringing quiet desperation and echoed sensitiveness to the forefront in a manner resembling emo lynchpins Bright Eyes and Dashboard Confessional. “In A Radio Song” offers supple classical folk warmth in a gently melodious mode similar to distinguished pacific saps American Music Club and Red House Painters. But those are strictly vogue comparisons overall. On Sheff’s greatest vocal performance, “A Stone,” his cracked bari-tenor brood conquers the grandiose cold-hearted glint with utter conviction. He pretty much summarizes Black Sheep Boy’s destitute oeuvre best with grievously soured stanza: ‘I know the bitter dismay of a lover who brought fresh bouquets everyday when she turned him away to remember some knave who once gave just one rose, one day, years ago.’

“It’s a dark record but there’s tenderness and playfulness. But people may never get that and instead think I’m angst-ridden and bleak,” he chuckles. “The phantasmagoric (titular) story is submerged with rejection. Yeah…‘Look at me, I’m a tormented self-pitying person.’ Like the Smiths, some think they’re funny and clever, others take them seriously. But I love to be pretentious, wide-ranging, and epic, biting off more than I could chew. So I countered that with the overblown, pompously perverse, five syllable wording of “So Come Back, I Am Waiting.”

Assuredly, Leonard Cohen’s influence slips into the grooves. Yet it’s tragic folk contemporary Tim Hardin’s moody composition, “Black Sheep Boy,” that serves as the vindicating overture.

“I love Tim Hardin’s first three records. Heroin led him down a path of diminished returns. He became a sad train wreck. I’d admired the compact wisdom of “Black Sheep Boy.” He’d kicked heroin, went home to Eugene, Oregon, but began using drugs again and wrote that song. I identified with the sense of doing something bad, screwing up, and acknowledging it’s a personal decision.” Sheff succinctly adds, “People dive into things they know are wrong but lose themselves in the abandon despite the consequences. It’s a horrible and glorious attitude. I wrote its sequel, “So Come Back, I Am Waiting,” as a dare.”

Temporarily picking up the pace of the weary-eyed collection are the avenging “Black” and harmonically cinematic “The Latest Toughs,” scattering electric piano vibrato atop busier beat-driven arrangements. Elegant mandolin frames the dusky trumpet-saddled “A King And A Queen,” gaining a sublime violin-cello seduction perfectly suiting the heartrendingly quixotic lyrics. On the dulcet countrified duet, “Get Big,” Sheff’s croaked whisper and Howard Draper’s sonorous lap steel interval counter guest Amy Annelle’s enticingly wispy croon.

“I love duets – George Jones and Tammy Wynette; Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris; Neil Young and Nicolette Larson. But I hadn’t coordinated the opportunity because it’s such a mad dash to get the records done. I was gonna get some famous female friend to condescend to one to give us massive sales, but I was too lazy,” Sheff laughingly divulges. “But Amy’s my favorite singer I’ve worked with. She has a fragile quality and had a cold the day we did “Get Big,” so her voice is real weak. It sounds like she’s crying.”

What Okkervil River will do next is anyone’s guess.

“Maybe we’ll do a new age record,” Sheff evidently kids.

True followers ought to seek out Spanish import, Julie Doiron & Okkervil River, an off-the-cuff 9-song dalliance with the former Eric’s Trip vocalist featuring congenial schizophrenic leftovers.