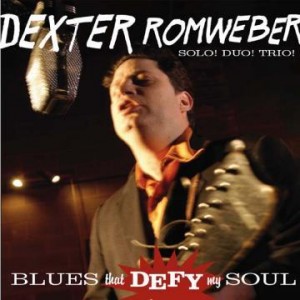

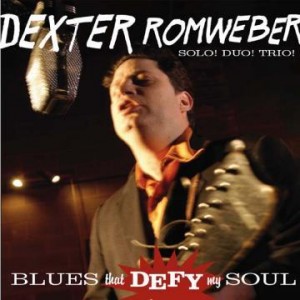

FOREWORD: Frenzied rockabilly throwback, Dexter Romweber, once led Chapel Hill’s well-respected Flat Duo Jets, a thrilling guitar-drums act whose passion, vitality, and determination was best showcased at smoky honky tonk joints and dank rock clubs. Under his own name, ‘04s Blues That Defy My Soul packed most of the energy of his live act on a solid-bodied studio recording, something Flat Duo Jets also did best on ‘93s White Tree. ‘06s Piano and ‘09s Ruins Of Berlin, Romweber’s follow-ups, remain uncovered by yours truly. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

FOREWORD: Frenzied rockabilly throwback, Dexter Romweber, once led Chapel Hill’s well-respected Flat Duo Jets, a thrilling guitar-drums act whose passion, vitality, and determination was best showcased at smoky honky tonk joints and dank rock clubs. Under his own name, ‘04s Blues That Defy My Soul packed most of the energy of his live act on a solid-bodied studio recording, something Flat Duo Jets also did best on ‘93s White Tree. ‘06s Piano and ‘09s Ruins Of Berlin, Romweber’s follow-ups, remain uncovered by yours truly. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

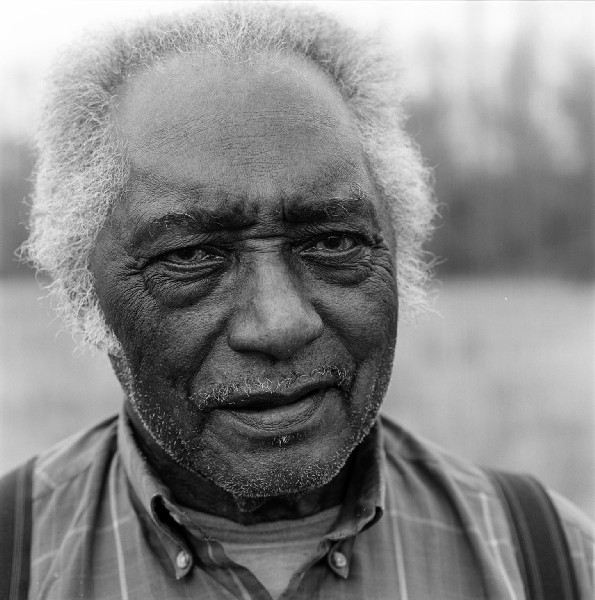

If Reverend Horton Heat was the ‘90s most feverishly liquored up rockabilly revivalist going then surely the finest primal garage rawk combo could’ve been the Flat Duo Jets. Pairing greasy-haired Silvertone guitarist Dexter Romweber with devilish crony Crow, this crazed Chapel Hill, North Carolina, twosome first took hold in Athens after REM and the B-52’s put that friendly Georgia college town on the map.

Initially invigorated by the cadaverous Gothic punkabilly of the Cramps, the Flat Duo Jets hootin,’ hollerin’ mixture of dusty classic rock stomps, front porch Country hoe-downs, raucous skiffle-flavored knockoffs, and schizoid boogie rumblings caught on with trendy stray cat strutters and “Hound Dog” lovers alike. Oft-times spewing growling baritone spunk like raving lunatic satirist Mojo Nixon, Romweber’s minimalist approach harks back to aging backwoods hillbilly wildman Hasil Adkins.

Following a primordial ’84 6-song fiesta, In Stereo (re-released in ’92), rustic relics Romweber and Crow returned to Carolina, made a far better surefire self-titled masterwork, then offered ’91s undisciplined grab bag, Go Go Harlem Baby, a year hence. Arguably the busy Duo’s most accomplished set, ‘93s handily diversified White Trees jumbled stylistically antiquated originals in a cohesively dignified manner.

But drug addiction, personal issues, and money troubles took their toll, halting the spiffy dualistic throwbacks by ’98. However, that did allow Romweber to hook up with Virginian pal Sam Laresh. A nutty stooge perfectly suited to replace Crow’s instinctual rhythmic rampage, Laresh had played regional dates with the Dexterous marvel in the past.

So the newfangled partners, recording under Romweber’s name, charged forth with ‘97s covers-only roots rock remedy Folk Songs and ‘01s scurried surf-garage wrangler Chased By Martians.

Picked up by sturdy Yep Roc Records, Romweber hopes better promotion and wider exposure will catapult ‘04s fascinatingly feral Blues That Defy My Soul beyond the reach of his loyal minions.

Perhaps Romweber’s tastiest treat yet, Blues gets the party cooking with hip Gene Krupa-like swagger on the scuffling anthem, “Rockin’ Dead Man.” Two zesty instrumentals, the Spaghetti Western-tinged “Nephretite” and the fierce fast-fingered shuffle “Nabonga,” boast radical gee-tar proficiency while the nasally snarled “Unharmonious” connects the yokel twang of unkempt folk freak Michael Hurley with the mannerly elocution of Johnny Cash. The bellowing outcry “You Broke My Heart” brings back memories of Eddie Cochran by-way-of Buddy Holly. On the tender side, “I’ve Lost My Heart To You” borrows its sentimentality from Elvis’ “Can’t Help Falling In Love.”

Perhaps Romweber’s tastiest treat yet, Blues gets the party cooking with hip Gene Krupa-like swagger on the scuffling anthem, “Rockin’ Dead Man.” Two zesty instrumentals, the Spaghetti Western-tinged “Nephretite” and the fierce fast-fingered shuffle “Nabonga,” boast radical gee-tar proficiency while the nasally snarled “Unharmonious” connects the yokel twang of unkempt folk freak Michael Hurley with the mannerly elocution of Johnny Cash. The bellowing outcry “You Broke My Heart” brings back memories of Eddie Cochran by-way-of Buddy Holly. On the tender side, “I’ve Lost My Heart To You” borrows its sentimentality from Elvis’ “Can’t Help Falling In Love.”

Who were your earliest musical inspirations?

DEXTER ROMWEBER: My brothers were into Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones. So I got into that. Like a million American teens, Kiss had this whole idea of getting onstage and making a spectacle – wow! It’s actually pretty bad music, but Kiss kicks ass. But when I listen to the Stones, that moves me emotionally. When they were starting to write their own stuff – “Heart Of Stone,” “Ruby Tuesday,” and “Out Of Time” –they were fantastic. An older musician that lived nearby taught me the 12-bar on guitar, which is the basis for rock and roll. So it wasn’t long before we were playing and doing gigs. My first band was the Remainz. We were a ‘60s garage-styled band playing the Stones’ “Fortune Teller” and the Monkees’ “I’m A Believer.”

My old drummer, Crow, was on rhythm-lead and my sister Sara, drums. Hunter Landen was the singer. He’s been in local bands like the Bad Checks and now the Chrome Plated Apostles. Our old band evolved into Crash Landon & the Kamikazes. We did whole sets – 16 songs. Remember the ‘80s rockabilly revival – we learned that stuff. Then, I bought re-issued Sun records and got rockabilly by Sonny Burgess, early Roy Orbison, and Billy Lee Riley. We started covering their songs. Then, it got more intense. We got into early rock and roll by the Coasters, Elvis, and Johnny Cash.

After Flat Duo Jets gained a stronghold in Athens, you moved back to Chapel Hill when Superchunk, Polvo, Archers Of Loaf, and Dillon Fence became elite indie rockers.

DEXTER: Those bands didn’t play the music I listened to. I was into Nick Cave, early Blues, especially Leadbelly, and Classical by Chopin and Bach. On my first solo record, Folk Songs, there’s some Classical.

I don’t own your first two solo endeavors.

DEXTER: They were on Permanent Records (an oddly ironic label name since they quickly went out of business). Chased By Martians was recorded during a turbulent period, but there’s good stuff on it. Not having the Duo Jets around to work with was difficult. Crow had to deal with personal problems. It was infringing on what we tried to do. Rock and roll, when you get into it, is a fucked up lifestyle. We broke up the band.

Going back to the Flat Duo Jets, Go Go Harlem Baby was recorded  by famed producer-pianist Jim Dickinson.

by famed producer-pianist Jim Dickinson.

DEXTER: It was a treat to work with Jim since he’s a rock legend. He saw us early on live and knew what we were trying to achieve. That record improved over time. I wasn’t crazy about it when it came out. Producers are weird, but he sat back and did his job with lots of spirit. My favorite albums include Safari, which at the time, we lied to the label and said the tracks were from ’84 to ’87. If we said they were new, the label would own them. There’s 32 songs, live, solo, and unreleased performances capturing all aspects. Wild Blue Yonder was strictly live, recorded during a tremendous ’96 tour where we came alive. Portions of White Trees I like. Then, (the last album) Lucky Eye, which had good stuff.

How’d you hook up with Sam Laresh?

DEXTER: When we’d play Virginia Beach, we’d sit around and talk. We had an affinity with each other. When me and Crow’d take a break, I’d sojourn to Virginia Beach and Laresh and I’d play clubs there. When the Duo Jets ended, he was right there as my sidekick. I didn’t want the end of the Duo Jets to end my career.

You’ve been considered the Godfather of modern guitar-drum duos, such as Local H, White Stripes, and Raveonettes.

DEXTER: I don’t take credit for that. On our records, we try to put bass and organ and not just make duo recordings. It’s a very easy set up. Buddy Holly survived on that. People would’ve done it anyway.

What’s the deal with your supernatural beliefs? You could let the eyes roll to the back of your head during performance. There’s a supposed obsession with Cajun voodoo. And rumor is you sleep in a coffin.

DEXTER: (laughter) I read spiritual literature, but it’s not voodoo. As for the eyes rolling back and the frenzy of it, that was in me anyway. When I gave up alcohol and drugs, it wasn’t as pronounced. But cigarettes are the most insidious drug of them all. Can’t quit ‘em.

Did you drunkenly amble through shows?

DEXTER: It was off the road when I didn’t have to work that I’d drink. I started fights, created a raucous. I was into whiskey and vodka. I haven’t drank in three years. Sometimes on the road I’d tie one on, but I’d try to hit the stage pretty sober.

Have you noticed any formative musical departures over your career?

DEXTER: Lucky Eye was a propulsion into something new. There was a time when the music was changing, but it was still original. It was in the vein of early rock but with something new added. Towards the end of the Duo Jets, that started happening. I went one step further to not sound fake. I tried to do away with tripped out role models that were self-destructive. I said, ‘I’m not gonna copy Lux Interior (of the Cramps), Jerry Lee Lewis, or Elvis. I’m gonna be myself.’ That made me feel more alive. I still do early rock screamers, but I don’t want to emulate anyone. The Cramps affected my life so much from age 15 to 18 – down to the black clothing, bones, horror stuff, and emeralds. They’re still really creative.

The title song, “Blues that Defy My Soul,” has a sinister Chi-town Blues groove and phlegm-y Screamin’ Jay Hawkins vibe.

DEXTER: I’ve been attracted to dark Blues, but I’ve found it hard to find. Big Band and folk Blues took over because I didn’t want to be conceived as rockabilly. There’s so many bands doing that. They have the look and everything. But it’s not the spirit of what it was originally about.

You’re not shy about doing obscure covers.

DEXTER: There’s an Andy Griffith ballad we do live no one knows about. He was in a really intense rockabilly movie, which the song is named after, A Face In The Crowd. He played a hellbent hillbilly-rockabilly guy.