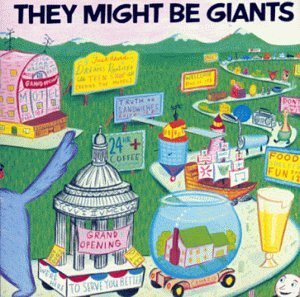

FOREWORD: I fell in love with They Might Be Giants from the beginning. Their cartoon video for the silly “Hotel Detective” and the quirky bounce of “Don’t Let’s Start” made their absurdly funny eponymous ’86 debut a dandy, one of the most wittily humorous rock albums since Steve Martin did “King Tut.”

FOREWORD: I fell in love with They Might Be Giants from the beginning. Their cartoon video for the silly “Hotel Detective” and the quirky bounce of “Don’t Let’s Start” made their absurdly funny eponymous ’86 debut a dandy, one of the most wittily humorous rock albums since Steve Martin did “King Tut.”

Fronted by the Two Johns (Flansburgh and Linnell), TMBG then became extremely prolific, something you wouldn’t expect from a few loose novelty-writing class clowns. ‘88s Lincoln brought forth the totally catchy hard rockin’ “Ana Ng.” ‘90s Flood boasted the equally hooky sentimental embrace “Birdhouse In Your Soul.” ‘92s Apollo 18 and ‘94s John Henry kept the ball rolling.

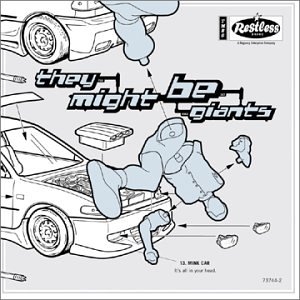

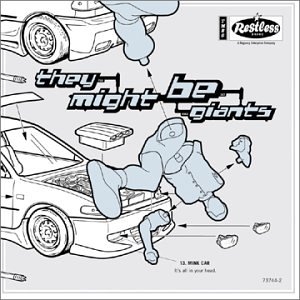

Used to performing tersely titillating tunes, it wasn’t a far stretch for TMBG to work on film songs, TV themes, and children’s records, and those are sprinkled amongst subsequently fine LP’s such as ‘01s Mink Car and ‘07s The Else. TMBG also offered Dial A Song phone jingles almost a decade before ring tones got popular. I originally interviewed Linnell for Smug magazine in ’88, but the following ’01 piece with Flansburgh is richer. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

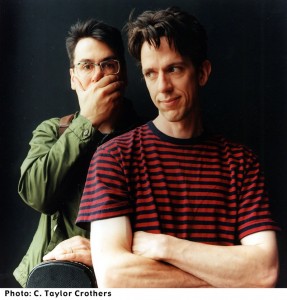

Growing up in the shadows of Harvard Square as an architect’s son, suburban Bostonian, John Flansburgh (vocals-guitar), met up with future They Might Be Giants partner, John Linnell (keyboards-accordion-sax-vocals) at their high school newspaper. They wrote articles, drew cartoons, and learned photography at an action-packed pace their fun-filled future band would benefit from.

Flansburgh then attended hippie-alternative Antioch College during the late ‘70s while Linnell spent a semester at Umass and played in savvy pop band the Mundanes (with future Beavis & Butthead producer John Andrews). By ’81, they caught up with each other in New York when Flansburgh was a Metro North-employed Fine Arts student at Pratt and Linnell, by chance, moved into the same Brooklyn building. They begam making home tape demos as a side project and began establishing a loyal local following with campy, frolicsome shows.

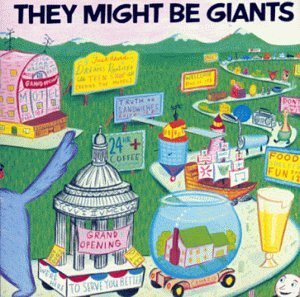

A sparkling self-titled debut of addictive mindless pop insouciance such as the bouncy “Don’t Let’s Start” and the cheesy “Hotel Detective” put They Might Be Giants on the map. Their cheery trinkets, sunny disposition, and rapturous spirit made a fiercely complicated world a little easier to take by offering an infectious remedy to relieve minor aches and pains.

A sparkling self-titled debut of addictive mindless pop insouciance such as the bouncy “Don’t Let’s Start” and the cheesy “Hotel Detective” put They Might Be Giants on the map. Their cheery trinkets, sunny disposition, and rapturous spirit made a fiercely complicated world a little easier to take by offering an infectious remedy to relieve minor aches and pains.

Lincoln’s spiffy, guitar-clipped ’88 splurge, “Ana Ng,” and Flood’s casually swaying ‘90 heart-throbber, “Birdhouse In Your Soul,” chugged along with the same melodic escapism the WMCA good guys stumbled upon as fast-moving DJ’s in the innocent craze of jingly jangly ‘60s AM radio. Amongst a dalliance of euphoric ephemera (Several EP’s, ‘98s Severe Tire Damage compilation, etc.) were full-length releases such as ‘92s Apollo 18, ‘94s John Henry, and ‘96s Factory Showroom.

Recently, TMBG finished up a two-month tour for the brand new Mink Car at historic Manhattan theatre, Town Hall. By shuffling the fabulous three-piece Velcro Horns around backup guitarist Dan Miller and bassist Dan Weinkauf (both formerly of the band, Lincoln), the Two Johns have expanded their whimsical domain.

Playing the part of a busy MC, Flansburgh’s jagged jokes, wacky wisecracks, and impromptu radio surfing (the band broke into an impromptu take on Argent’s “Hold Your Head Up” and an unspecified Latin jam as he kept searching ‘round the dial) were given expediency by Linnell’s punctual multi-instrumental dexterity. One unexpected highlight came when amazing drummer Dan Hickey (Joe Jackson/ B-52’s) merged style-shifting drum solos ranging from Jazz legend Buddy Rich to lunatic mod rocker Keith Moon with pizzazz.

On record, the exuberant “Bangs” and the rubbery “Cyclops Rock” get Mink Car off to a fast start. By combining Giorgio Moroder’s robotic ‘70s disco beat with the Pet Shop Boys ‘80s new wave, “Man, It’s So Loud In Here,” gets swept away by club-bound romanticism. After the puppy love ballad, “A First Kiss,” things get rockin’ again. The bass-bustling Blues-siphoned “I’ve Got A Fang” gains exotic flavor from its snake charmer keyboards while the fuzzy take on Georgie Fame’s “Yeh Yeh” (mixed by Fountains Of Wayne pop idol Adam Schlesinger) will get fingers snappin’ and spines shakin’ in no time.

Besides gaining further exposure with the punk-throttled Malcolm In The Middle theme song, “Boss Of Me,” the dynamic duo previously licensed “Dr. Worm” for the kiddie animation Kablam! and created “Doctor Evil” for Austin Powers’ The Spy Who Shagged Me. Acclaimed filmmaker AJ Schnack will celebrate TMBG with their 20th anniversary documentary Gigantic (A Tale of Two Johns) in 2002.

Do you feel They Might Be Giants provide humorous social critique for an audience too caught up in post-modern irony?

FLANSBURGH: In our culture, if you’re not caught up in proving your authenticity, it’s hard to say where your pop consciousness begins and ends. I don’t feel we’re commenting on our culture. I realize we touch on familiar ideas, but the general impulse comes out of the same impulse any songwriter would have. If people label you ironic, it’s one step away from being cynical. We’re extremely un-cynical, especially compared the popular music on the horizon. I feel we’re uncalculated and distant from the notion of being some snarky, sarcastic thing. There’s joy in what we do; a celebratory aspect. It’s the power of a good time party band. I don’t mind being pigeonholed, but I get the impression we’re summarized as being mean-spirited. We’re a complicated band with a range of songs and intentions.

The hopeless romanticism of simple pop goiofs like your debut’s weak-hearted “Don’t Let’s Start”, Flood’s affectionate trinket “Birdhouse In Your Soul,” and Mink Car’s heartbroken “Cyclops Rock” get to me emotionally the same way bubblegum staples “Love Grows (Where My Rosemary Goes” by Edison Lighthouse and Bobby Sherman’s “Easy Come, Easy Go” once did.

FLANSBURGH: I did a cover of “Love Grows” with my college band, the Turtlenecks, in Ohio. We did half-originals, half-covers.

I first got into TMBG after watching a cartoon version for the ditty, “Hotel Detective.”

FLANSBURGH: That was the third video we did. After being a local band for four years, we started touring in ’86 and became almost a viable national act.

Your live show continues to evolve.

FLANSBURGH: We want to rock the crowd, but that tempers the amount of slow songs we like to do. There’s a tyranny to the uptempo song. They dominate because they work on such an immediate level. Happily, we haven’t had a career where one song eclipses what we do. We’ve had minor successes which makes it easier to do an entertaining full length show. But if we don’t do “Birdhouse” or “Istanbul (Not Constantinople)” people would think we were being prissy. We’re obligated to do those because they hold a place In people’s minds and hearts. But I don’t feel any distance from our earlier stuff.

Mink Car may contain your catchiest songs since the debut.

FLANSBURGH: Thanks. That’s high praise.

“Bangs” has a highly accessible multi-layered ‘60s-styled feel-good flow.

FLANSBURGH: We worked on that with Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley (respected Brit-pop producers who’d previously worked on “Birdhouse”) spending time figuring out how to build the song up. It’s surprisingly simple considering how thick it gets by the end. I love that song.

What does the crazed female scream for “Cyclops Rock”?

FLANSBURGH: Cerys Matthews of huge British band, Catatonia. She’s a notorious wild girl in England. They were working with Clive on their LP at the same time. We were gonna get Joe Strummer to do a chant section, but we finished before that could happen.

Besides cool rhyming by Soul Coughing’s Mike Doughty, “Mr. Xcitement” features Elegant Too. What’s their background?

FLANSBURGH: They’re a production crew who are all over that track. They’ve got great ideas on how to approach electronic music. They do TV and soundtrack work. Chris Maxwell (ex-Skeleton Key) is a great guitarist and I worked with drummer Phil Hernandez on my side project, Mono Puff. It was a gas doing sessions with them. We had a bunch of horn blasts created for us to manipulate experimentally in the computer. It takes the driving beat of “Peter Gunn” and morphs it into a drum ‘n’ bass idea.

You cover Georgie Fame’s late ‘60s British #1 hit, “Yeh Yeh” on Mink Car.

FLANSBURGH: The original was done (by second-tier pop trio) Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. I’ve never heard it, but have heard of it. It’s impossible to locate. The Georgie Fame version is even faster than ours. It’s hopped up and manic.

You did a song “In The Middle” at Town Hall. You said it was to be released on a children’s album. Who was the female singer onstage?

FLANSBURGH: That’s my wife, Robin Goldwasser. She sang “Doctor Evil” for Austin Powers’ soundtrack. We’ve got an all-original children’s album, No, due in spring. Though people wouldn’t think of it as a departure from TMBG, it really was. It took awhile to crack the code of keeping kids interested. We bought various rock-related children’s records, but some were too repetitive. We wanted it to have a ‘Seussian’ quality.

How did the perfectly obnoxious parent-dissing Malcolm In The Middle theme, “Boss Of Me,” come to fruition?

FLANSBURGH: We just had a top 20 UK hit with that. That song is like the son of “Twistin’” from Flood. It’s structurally different, but in terms of energy, it’s not uncharted territory. We wrote it a few years before the show came on.

Do you feel an affinity with Mark Mothersbaugh (ex-Devo) or Danny Elfman (ex-Oingo Boingo) since they do the Rugrats and The Simpsons themes and formerly led humorous underground rockers like TMBG?

FLANSBURGH: It’s strange that it has become a path for alt-rockers. But it’s not a big surprise. The only thing you need to have going for you is an open sense of musicality. We’ve done background music for Malcolm and incidental music for The Daily Show with John Stewart and ABC’s Nightline. They’re all different gigs. Much of it is hard to recognize as TMBG. It’s fun to stretch out and do orchestral work not leaning on lyric writing. It’s an interesting challenge and a natural progression.

Tell me about the internet-only Long Tall Weekend.

FLANSBURGH: You can’t get it in stores. It was made for an entirely different generation of college kids downloading material. Because not everybody is wired, there are barriers. But there’s no manufacturing costs or physical component and it sold 20,000 of pure profit. Mink Car is a straightforward LP with wide ranging material. Long Tall Weekend was a crazy compilation like The Who’s Odds & Sods with unusual songs like “Edison’s Museum.” Factory Showroom (’96) was our last studio album. The first place our newer songs show up are on the ‘Dial-A-Song’ phone service. But the MP3 monthly subscription service on E-music – They Might Be Giants Unlimited – features a dozen songs per month with 3,000 subscribers. There’s an unquenchable thirst for new material. But the best songs go on our proper albums.

Give me the scoop on the seasonal Holidayland.

“Santa Clause” is a ‘60s cover from garage band, the Sonics. It’s a rough recording that captures the vibe of the Sonics. “O Tannebaum” is very close to its original German version. There’s toy piano on “Feat Of Lights.”