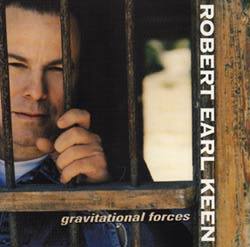

FOREWORD: Houston-born singer-songwriter Robert Earl Keen was one of the most significant independent Country & Western finds in the ‘80s. He made good on that promise with several ambitious albums, leading to ’01s delightful Gravitational Forces. Slowing down on recording sessions thereafter, Keen continues to live off his solid rep in concert, releasing occasional studio albums (‘03s Farm Fresh Onions and ‘05s What I Really Mean). This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Reputable singer-songwriter Robert Earl Keen began playing music while attending Texas A & M with fellow Country & Western artist Lyle Lovett, penning “This Old Porch” for his yet-to-be-famous college friends’ eponymous debut. After graduating, Keen settled in Austin, became a solo act, then drifted off to Nashville when fellow Texas troubadour, Steve Earle, convinced him it was the right move.

After ‘84s formative No Kind Of Dancer and its delayed follow-up, ‘88s The Live Album, produced by seasoned knob-twiddler, Jim Rooney (Townes Van Zandt/ Nancy Griffith), he hired a booking agent and moved back to the Lone Star State.

Featuring the live staple, “The Road Goes On Forever,” which has been covered by Willie Nelson, the Highwaymen, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Joe Ely, and Kris Kristofferson, ‘89s West Textures brought onboard a number of newly impressed Dallas and Austin fans.

But by ’93, Keen felt ‘stuck in nowhere land’ waiting for national exposure and recorded his most diverse, consistent record to date. A Bigger Piece Of The Sky, with bassist Gary Tallent (from Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band) and guitarist George Maranelli (Bruce Hornsby/ Bonnie Raitt), secured small-scale national attention.

When ‘94s Gringo Honeymoon dropped, he went from selling out New York’s smaller Bottom Line to getting gigs at larger venues such as the now-defunct Tramps and Irving Plaza. ‘96s live No. 2 Diner neatly captured Keen’s concert excitement, boasting a great repertoire, including the catchy fish tale, “Five Pound Bass,” the Flying Burrito Brothers-by-way-of-Dylan country-rocker, “Think It Over One Time,” and the high-rollin’ barroom stomp, Amarillo Highway,” along with tidbits of funny ‘tween song dialogue.

A stint at Arista Records produced two fine albums, ‘97s Picnic and the follow-up, Walking Distance. But obtaining aboveground Country and folk fame was out of reach.

Since being let go by that major label, Keen has continued to please sold-out audiences. And recently, he unleashed the mighty fine, Gravitational Forces. Helped out by a tight touring band and former Small Faces keyboardist Ian McLagan (on acoustic lullaby “Not A Drop Of Rain” and somber “Goin’ Nowhere Blues”), his ninth album collects a ‘colorful, shimmering’ version of Townes Van Zandt’s pretty “Snowin’ On Raton,” Johnny Cash’s longing “I Still Miss Someone,” and the traditional folk standard, “Walkin’ Cane.” Originals such as the sweepingly sentimental “Fallin’ Out” (which has the same delicate tension as John Prine’s best material), the lonely steel guitar weeper, “Wild Wind,” and the Texas boogie hoedown, “High Plains Jamboree,” round out the ambrosial long-player perfectly.

At a packed Bowery Ballroom show earlier this year, there were more hard drinkin’ Texans over six-feet-tall gathered North of the Confederate Border to witness Keen perform than possibly imaginable. So it goes without saying that his fabulously successful Texas Uprising series is a must see. This year, Keen’s concert cohorts included established acts such as Los Lobos, Kelly Willis, Slaid Cleaves, and Todd Snider, along with local upstarts Nickel Creek, Beaver Nelson, and Reckless Kelly.

I spoke to Keen a few weeks before his latest Irving Plaza jaunt.

Though you didn’t pen it, Joe Dolce’s (the author of Italian parody, “Shaddap You Face”) “Hall Of Fame” was ironic with its stanza, ‘my home ain’t in the hall of fame/ you can go there but you won’t find my name,’ definitely struck a nerve. Here you are, a respected cross-country concert attraction and an accomplished songwriter covered by George Strait, Lyle Lovett, Nanci Griffith, Dar Williams, and Joe Ely, yet watered down contemporary Top 40 Country radio remains stuck in a rut and will not acknowledge your roots-based music.

KEEN: I got that song off a Jonathan Edwards record (Bluegrass Staple). J.D. Crowe also did it. It’s one of those songs I never did onstage, but it was perfect while drunk at a campfire. It’s my kind of song.

Then comes the acoustic affectation, “Hello New Orleans.” That must fit in well with the party crowd down on Bourbon Street.

KEEN: Right. The only problem with New Orleans is they always want you to go on at midnight. I’ve got people who go to bed at 12. (laughter)

Are your songs usually fictional?

KEEN: It goes from completely absurd to real straight-on accounts. My barometer or litmus test is ‘does it feel true?’ That’s what I count on. When I write sentimental songs, I’m just trying to please myself. If that stops, I don’t have the heart to go on. I like performing onstage. I’m not any kind of singer and a mediocre guitarist, but I write good songs.

Give me some of your current bands’ background.

KEEN: Marty Muse (pedal steel0 moved in from Spokane, Washington, ten years ago. He played with the Derailers and Rick Trevino. He’s tasteful; not flashy. I always tell him we need more purple sunsets here or there. Bassist Bill Whitback is a musicologist. Before he played with me, he did Country covers at local dancehalls. Guitarist Rich Brotherton I’ve been with for eight years. He’s originally from Augusta, Georgia. His main gig was Toni Price. Drummer Tom Van Schaik left the Dixie Chicks before they exploded because he thought that would be too crazy.

Your career neatly parallels that of Canadian troubadour Fred Eaglesmith. You both put out lots of independent albums and remain under-appreciated by mainstream audiences.

KEEN: I did a lot of shows with him for five years. He’s a killer. He packages his cassettes in wooden boxes which is an odd marketing idea and weird format. Fred writes interesting songs about great topics. He’s also truly a great, intense conversationalist.

I’m proud of Country artists like Eaglesmith, Lucinda Williams, and you, who’ve bypassed Country radio and succeeded on their own terms.

KEEN: I had my problems getting Picnic and Walking Distance promoted to radio. Arista Records wasn’t interested. They signed me to keep me off the street. (laughter) I was floored by what indie labels offered so I sat back and enjoyed that. I decided to start Gravitational Forces before I signed with anyone, People were breathing down my neck before Lost Highway signed me.

Does the title, Gravitational Forces, refer to the forces which have kept you from being accepted by mainstream Country formats and corporate hacks?

KEEN: I think I came back and landed where I was drawn to. Some of my friends say this is more like my early records. My favorite is Bigger Piece Of The Sky. It’s all over the map and lyrically it’s really colorful.

What’s on your CD player these days?

KEEN: In my pickup truck there’s The Good The Bad And The Ugly soundtrack, Joe Buck, Kasey Chambers. My favorite new Texas artist is Beaver Nelson, a loopy neo-hippie with stream of conscious lyrics – which is something I usually don’t like.