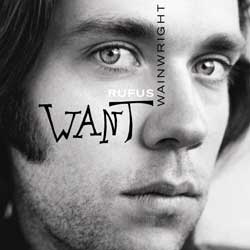

FOREWORD: I’ve spoken to Rufus Wainwright on several occasions at other musicians’ shows. He’s friendly, polite, and was reared by two semi-famous musical parents. So I was looking forward to speaking to the stylishly serenading tunesmith when the gorgeously orchestrated Want One dropped in ‘03. When we left off, the environmentally conscious gay-rights advocate was hoping to become more politically aware in order to rebuke fascist Republicans. After ‘04’s Want Two, Rufus came up with ‘05s splendid guest-filled Release The Stars and ‘07s Rufus Does Judy At Carnegie Hall (a ripe tribute to the late, respected Judy Garland).

Chasing away personal demons to rid deep depression becomes cumbersome, but soon skies brighten and beams of sunshine re-invigorate lost souls. Happily, composer Rufus Wainwright overcame the trauma of alcohol indulgence and speed abuse to return stronger than ever. Musically gifted son of satirical singer-songwriter Loudon Wainwright III and folk romanticist Kate Mc Garrigle (one-half of Montreal’s resplendent Mc Garrigle Sisters), the resurrected Rufus reconvened his recording career after a short October 2002 rehabilitation.

Learning to play piano at age six, Rufus Wainwright toured with the Mc Garrigles alongside sister, Martha (also a respected performer), by thirteen, getting nominated a year hence for the equivalent of a Canadian Oscar with the composition “I’m A Runnin.’” By ’98, his self-titled first album of original ‘modern standards’ turned heads due to its oblique pre-rock leanings, baroque elegance, Chamber pop twists, and informed Classical nuances. Recondite string conductor-producer Van Dyke Parks (fresh from his ’95 Brain Wilson collaboration Orange Crate Art) and French Canadian multi-instrumentalist Pierre Marchand (who’d scored hits with crooner Sarah Mc Lachlan) lent a hand, as did veteran rock sessionmen Jim Keltner (drums) and Benmont Tench (keyboards). The gorgeously yearning serenade, “April Fools,” found radio daylight, securing an eclectic audience for the eccentric, seductive tenor.

For ‘01s evocative Poses, Wainwright’s baritone gained further assuredness as he nailed leftover material from his promising debut. Now living in New York City’s Chelsea District, the fragile artist succumbed to reckless self-destructive behavior by the time 9-11 shook the foundation surrounding his pacific neighborhood. While finalizing rehab, Wainwright began drafting “Want,” the auspicious titular theme framing an exciting new chapter.

Linking ecstasy, passion, and pain, the Manhattan transfer courageously exposes his most vulnerable lyrics on the reflective Want One (a second installment, Want Two, is expected shortly). Experienced producer Marius deVries’ rich orchestral tapestries – whose embellishments adorn the works of top-notch pop artists such as Madonna, Bjork, Massive Attack, and David Bowie – give a sweeping dramatic splendor to Wainwright’s thoughtful vistas and complex arrangements.

Linking ecstasy, passion, and pain, the Manhattan transfer courageously exposes his most vulnerable lyrics on the reflective Want One (a second installment, Want Two, is expected shortly). Experienced producer Marius deVries’ rich orchestral tapestries – whose embellishments adorn the works of top-notch pop artists such as Madonna, Bjork, Massive Attack, and David Bowie – give a sweeping dramatic splendor to Wainwright’s thoughtful vistas and complex arrangements.

The hymnal bolero “Oh What A World” drifts through childhood remembrances, the New York skyline, and Broadway show tune “Memories,” building to a plush string crescendo. “Movies Of Myself” embraces more innocent recollections, gaining sturdy guitar resilience from guest Charlie Sexton while comparing favorably to Todd Rundgren’s best beat-driven Something/Anything tracks (ironic, considering both albums were made at Woodstock’s soon-to-be-closed Bearsville studio). Penned as a lovingly bitchy lament to his Boston Public father and featuring his mother on accordion, the gently swaying “Dinner At Eight,” confronts heartbreaking rebelliousness compassionately.

How did Want One shape up?

RUFUS WAINWRIGHT: I definitely pulled out all stops for this record and its follow-up, Want Two. I went into the studio, none of this was planned, and the war was starting in Iraq. Marius is an extremely efficient, polite, diplomatic producer. I had dealt with some major personal issues. We just started working and shot out thirty tracks. We ended up with two records. At first, I wanted to do a double LP. The record label was weary and I don’t want my listener’s heads to explode. So I thought of an installment deal because it reminds me of a Victorian novel. In terms of marketing, we didn’t want any strikes against Want One. There are certain songs my fans know from concert, like “Gay Messiah,” that are on Want Two. I didn’t want to edit, cut down, or bleep anything and I wanted to get into Wal-Mart, at least the first part. Then, the second part, you could sell at Barnes & Nobles.

Are you the “Gay Messiah”?

RUFUS: No. I’m Rufus the Baptist. I won’t be the one baptizing in come. It’s my take on religious right wing attitude towards the politics in the world. I can’t even enter into the debate because in terms of those religions, gays don’t exist. So I created the “Gay Messiah,” who rectifies the situation.

Were you brought up religious?

RUFUS: I was never baptized, but I was brought up in a very Catholic environment and school – not so much household – but I had to go to church. I wasn’t allowed to take Communion. I wasn’t allowed to do Confession. I think my mother wanted to put me through extreme hell. (laughter) In a weird way, I wasn’t part of the church, but the Bible stories are pretty amazing. I’m happy I went now. At least I know the enemy.

Your mother and Aunt Anna have angelic hymnal voices. Did they sing church choir?

RUFUS: Quebec is haunted by the Catholic Church as a province of mind. There was a cultural revolution in the ‘60s – no, that was China. It was maybe the Silent Revolution. It was real anti-Catholic. They went from having the highest birthrate in the world to the lowest. So the church haunts everyone.

Did the circumstances of 9-11, rehab, and other adversities play a part in Want One’s development?

RUFUS: It did. You’re right. I don’t think it’s necessarily adversity so much as dealing with adversity, getting out of adversity, and realizing life is worth living and regaining hope. This record’s positive in many ways – on the upswing. I was practically born onstage. My first crib was a guitar case and I always associated performance with love and songwriting with social standing. For many years, I wasn’t aware I was a person like everybody else. That person who was ignored came back and whipped me in the ass when I hit thirty.

The flourishing orchestral dirge “Go Or Go Ahead” resonates with personal defeat.

RUFUS: That song was a gift from hell. I definitely had to pull in a lot of favors from a vast amount of mythological tales or lessons taught by my father. I had to grab all those things in my life to keep it together. That song encapsulates much of that.

On the other hand, radiant piano and prominent horns give “14th Street” a celebratory feel.

RUFUS: That’s the triumphant return. I was recently in Paris. They put me up in the Arc of Triumph, and that reminded me a lot of that song – a big triumphant arch. The knight returning home from battle.

The vocal arrangement for “Vicious World” reminded me of Todd Rundgren.

RUFUS: That’s in homage to Brian Wilson. Hats off to Brain for the harmony parts.

Pure vocalists are hard to find nowadays.

RUFUS: I like Thom Yorke (of Radiohead). Beth Orton is great. I also love Edith Piaf, Serge Gainsbourg. Then again, I’ve been listening to Chicks On Speed’s “We Don’t Play Guitars” for fun.

Cole Porter has been mentioned as your mentor.

RUFUS: He’s the man in terms of molding lyrics and music into one big fat punch. I definitely love Cole Porter’s ability to on the one hand be dry, calculating, and economical and on the other, really rip your heart out – which I think, is completely lost these days.

Besides Schubert, who are Classical influences?

RUFUS: I’m enamored with Schubert because he was basically the first songwriter ever, especially on the piano. He took the song form out of the folk realm and made it into a powerful epic journey. He performed a lot of his songs alone at the piano. He’s the seed or plant I grew out of. I owe him a lot. There’s more emotion, guts, and beauty in one moment of his music than there is in entire operas by other composers. He has these little supernatural gems in his music. So I aspire to him. But my main love is Russian, French, and German opera by Puccini, Verdi, Wagner, and Strauss. It literally happened overnight. I relate to opera in terms of my life as a teenager because when I was 14 I knew I was gay and AIDS was making its first big noise. Being gay was related with death. So I related to that desperation.

How do Van Dyke Parks string arrangements on your debut compare to deVries work on Want One?

RUFUS: Van Dyke Parks basically wrote string arrangements for the first album. He’s responsible for me being signed. He heard my tape through a friend and said, ‘This guy has to be signed’ and went straight to Lenny (Waronker-label exec). I owe everything to Van Dyke. Marius, after many debacles, became the perfect producer for me. I have lots of ideas before going in the studio. I just spew out tangles, which some producers hated, or were intimidated by. Marius was excited by what I had to say and enjoyed the process. I’d get my rocks off and go away, he’d do his thing, and by the end, we’d get out big machetes, chop stuff out, and make a sculpture.

What hobbies do you have outside music?

RUFUS: I go to the opera and enjoy cross-country skiing. I read more to get smart so I could argue better against Republicans.

Have you read Al Franken’s Liars and the Lying Liars That Tell Them?

RUFUS: I just bought that book. I think it’s all out war next year against the bad guys in the Bush administration. It’s important to have certain ideals; otherwise they’ll be taken from you.

If you need satirical sociopolitical advice, go to your father, Loudon.

RUFUS: (laughter) I probably will. He’s living in L.A. now.