Dozens of worthy ‘Confederate’ garage combos place emphasis on real or imagined liquored-up bravado to push across their assertively masculine clamor. Unlike notorious ‘70s-sojourned Alabama slammers, Lynyrd Skynyrd, astoundingly undervalued present-day denizens such as white-knuckled cow-punks Slobberbone, backwoods blues-hounds the Neckbones, folk-blues truck-stoppers North Mississippi Allstars, and, offhandedly, sci-fi surf rockers Man Or Astroman, never received the recognition due them. Hopefully that may change somewhat with the latest round of younger Dixie dwellers.

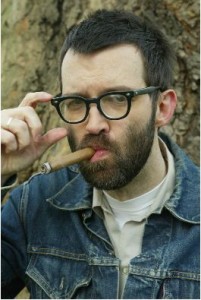

Dexateens frontman Elliott McPherson is a working class cabinetmaker with a wife, two kids, and three (or more) band mates. Formerly in developmental group, the Phoebes, as a post-pubescent adolescent, he and long-time drinking pal, Craig ‘Sweet Dog’ Pickering soon began jamming together in respected college town, Tuscaloosa. Attending University of Alabama alongside kindred spirits, bassist Matt Patton (Who-fueled Model Citizen axe man) and guitarist John Smith (ex-American Cosmic), the spunky crew became youthful protégés of local rebel rousers, the Quadrajets.

“Pay The Deuce is one of my all-time favorites,” McPherson maintains. “It sounds like it was recorded with the tape and band literally on fire. When we heard that, we ended up using the same staff for our self-titled debut. (Experienced Texas garage-punk lynchpin) Tim Kerr did production. We were so inspired by that record. Thank goodness we got entirely different results. That Quadrajets lineup was completely off the hook live.”

Some have compared the Dexateens formative ’04 debut to ‘60s psych-rock legends, the 13th Floor Elevators, but McPherson claims it was closer to “gritty shit kickin’ punk.” As the band progressed, they tended to gradually mellow over time, as ‘05s Red Dust Highway leaned towards humble Southern-fried hoe-downs.

Simialrly, ‘07s diversified breakthrough, Hardwire Healing (Skybucket Records), presents a trusty collage of earthy Blues contrivances, lazy 6-string strolls, and delicate acoustic turnabouts. Nevertheless, hard-hitting Neil Young-distilled grinder “Makers Mound” brings the noise counteracting simmering changeups such as ‘Downtown,” a sleepy-eyed respite suggesting tragic lo-fi minstrel Elliott Smith’s pallid tranquility.

“I wasn’t allowed to listen to (modern) rock as a kid,” McPherson admits. “I had a bunch of my dad’s old 45’s by Elvis Presley and Lesley Gore. I remember listening to lots of Waylon & Willie in the early ‘80s. But John Smith’s always been the cool kid on the block, even though he’s not a hipster by any stretch of the imagination. At 17, I was in a band with his brother. John turned me on to Velvet Underground and the Stooges. He’s responsible for most of the stuff I know. I was completely sheltered not having rock in my house. My family didn’t think it was morally correct.”

That, of course, changed when McPherson started college and met friends who’d open his mind. Though there was no formal Tuscaloosa scene, defunct club, The Chukker, provided limited exposure. However, Athens, Georgia, 100 miles northeast, had many bands sharing a special camaraderie with much larger audiences.

McPherson explains, “They were making soulful music in Athens. You take things away from every relationship developed and it enhances what you do creatively by getting sucked into it. Besides, Tuscaloosa has become real corporate and they’re trying to fit in as many people as they can lately. Our football coach (Nick Saban) we’re paying millions.”

Co-producers David Barbe (Sugar alumnus and Son Volt board man) and Patterson Hood (Drive-by Truckers mastermind) helped guide Hardwire Healing towards broadened versatility, permitting sundry melodious colors and sonic textures to forge a wide-ranging musical spectrum.

Co-producers David Barbe (Sugar alumnus and Son Volt board man) and Patterson Hood (Drive-by Truckers mastermind) helped guide Hardwire Healing towards broadened versatility, permitting sundry melodious colors and sonic textures to forge a wide-ranging musical spectrum.

“We knew we’d have a fun vibe – drink beer, laugh, tell stories, and roll tape,” McPherson informs. “It was very laid-back and peaceful, done in one day, eight songs. People compare us to Drive-By Truckers. Patterson laid his hands on our songs, but not specifically. He knew how to let us groove on a beat.”

Nonetheless, strangely sedate saunter, “What Money Means,” and twangin’ agrarian allegory, “Fyffe,” undeniably recall DBT’s grimaced hillbilly grime.

About the latter fictitious song, McPherson says, “In Buhl, where I live, there are crazily paranoid rednecks who feel the government is holding out on them. Fyffe is a nearby area with various UFO sightings. Patterson had a great song about putting people on the moon. But this was a completely different and comical stab. Patterson’s a fan of E minor and that song’s in that key.”

Another Hardwire Healing highlight, “Neil Armstrong,” sustains a rural alt-Country contentment reminiscent of reticent ‘80s trailblazers, Uncle Tupelo. Written by Smith for his old band, the resonantly euphonious tune begs an individual to get real, be honest, and come back to earth as pastoral slide guitar glides through sensitive vocalizing in a manner indicative of the Flying Burrito Brothers. Also redolent of the Burritos, specifically their revered Country-rock pioneer, Gram Parsons, is undiluted acoustical folk retread, “Own Thing.” Perhaps most appealing, lead track “Naked Ground” plies coil-y Southern rock twin guitar lattice to dirtied-up Delta Blues ruggedness.

McPherson accepts the last notion, avowing respect to a few distinguished folk-Blues septuagenarians. “We spent a lot of time with T-Model Ford and Paul Jones. We got to do short tours with both. I remember hearing T-Model the first time. I’d never heard anyone play guitar like that. He didn’t have a clue what the pentatonic scale was. There are all these asshole Blues guys doing Stevie Ray Vaughan guitar licks. Here you got this guy from the country who learned guitar in his 50’s and has more soul and heart than any of those fakes.”

Next on tap for the Dexateens is an EP entitled “Lost & Found,” featuring Smith’s Big Star-influenced songs written while he was away from the band. Plus, an ‘08 full length monster truck-enthused disc, Single Wide, recorded in Nashville, will showcase totally acoustic songs with live vocals, no drums, but varied percussion affects. They evidently overdubbed the hell out of it.

“We’re not a band that writes ballads,” McPherson shrugs. “It’s just a natural progression coming out of our teen years with fire and energy and piss and vinegar. We’re together a long time and our music has morphed into what it is. But I don’t want Single Wide to come out like Hotel California.”

Auspiciously, several indigenous players fill in onstage when McPherson’s core members need to take care of homebound business (or family) obligations. The traveling troupe variably includes Woggles drummer Dan Electro, Model Citizen bassist Craig Gates, Benders guitarist Tommy Sorrels, and charismatic Spidereaters leader Taylor Hollingsworth.

Disturbingly, CMJ Music Marathon has put the Dexateens on the backburner for its annual October New York shindig. McPherson snips, “We’re on standby. Fuck that!”

He concludes, “I don’t know. We may be too dumb to quit. But we certainly have retained a good amount of interested fans. We’re not willing to trade our families to go out on the road for an extended period of time. We go to Europe occasionally and have received a nice response. But we haven’t made it to New York City yet.”